There are an estimated 17,000 brown bears, 12,000 wolves, 9,000 lynx and 1,250 wolverines living in Europe – nowhere near historical levels, but a healthy amount all the same. But what’s more surprising is that these populations are found in the same places as people.

In a new study in the journal Science containing the most exhaustive data set ever collected on large carnivores in Europe, Guillaume Chapron and colleagues found that not only are all four species surviving in human-dominated landscapes, but their populations are generally stable or even increasing.

Move over Hugh Jackman, this is a real wolverine. NH53

The results could be considered surprising. With its dense human population and highly developed landscape, Europe isn’t exactly the place you would expect to find healthy populations of wolves and bears. But the study has confirmed that Europe has actually has a higher density of wolves than the lower 48 states of the US.

Europe success story

So what is Europe doing right? The paper identifies several combining factors. Key legislation – such as the Bern Convention and the Habitats Directive – has given these animals at least some legal protection across Europe.

In addition, the large numbers of herbivores such as deer and bison needed to sustain carnivore populations have made a comeback. And large numbers of people have moved to cities, lowering human impact on wildlife in the countryside.

But Europe’s conservation model is the real key to its success. Europe has developed a model of co-existence of people with predators – and sustainable populations of large carnivores are now reappearing in places where people live.

The lynx is Europe’s largest cat. Miha Krofel

“In the US conservation is based on the principle of wilderness”, says Chapron, “which is the idea that wild animals such as large carnivores are supposed to be out there far away in unspoiled, undisturbed areas.”

But if this model was applied in Europe, the continent wouldn’t have any large carnivores; the protected areas are simply too small to allow for self-sustaining populations.

“In the past there was a big push for conservationists to use the protected area approach, where they believed that wildlife could only really exist away from humans,“ said Niki Rust, a researcher in human-wildlife conflict. “But the study clearly shows even species that might seem annoying – such as large carnivores – are coexisting with people.”

What about Britain’s bears?

So with mainland Europe witnessing a shining conservation success story, will the UK – currently home to no wild large carnivores at all – be next? It’s tricky. Though people may be largely supportive of reintroducing wild predators, there are several serious concerns.

Fear is a big factor, says Robert Young, a wildlife conservation expert at the University of Salford. Says Young: “It doesn’t matter where you go in the world, people are scared of having large carnivores nearby.”

Young thinks this fear, escalated by the headlines any attack by a wild animal inevitably brings, makes people lose perspective. “The road system is probably thousands of times more dangerous than co-existing with these carnivores and yet we don’t have people saying we must fence off the roads,” said Young.

There are also differences from mainland Europe. Britain has an extremely high human population density and also eradicated its large carnivore population far earlier than many places in mainland Europe.

Says Rust: “People have lived without them for so long that they don’t know how to exist with them. I don’t think that in the next 50 or 100 years we will see large carnivores come back to the UK.”

But Young is more optimistic: “Many countries in the world deal with livestock and with having these carnivores around so I don’t think these problems are insurmountable.”

And there could be advantages to reintroducing these animals in the UK. Deer can have a big impact on native forests due to their selective browsing on young trees. As well as helping to control numbers of deer, the presence of wolves may encourage deer to steer clear of forested areas where they are more vulnerable to wolf attacks.

New questions raised

Now we know modern Europe can sustain populations of large carnivores, the inevitable question then becomes: how many are actually wanted? Is the minimum amount to provide a sustainable genetic pool ideal? Or should it be as many as possible?

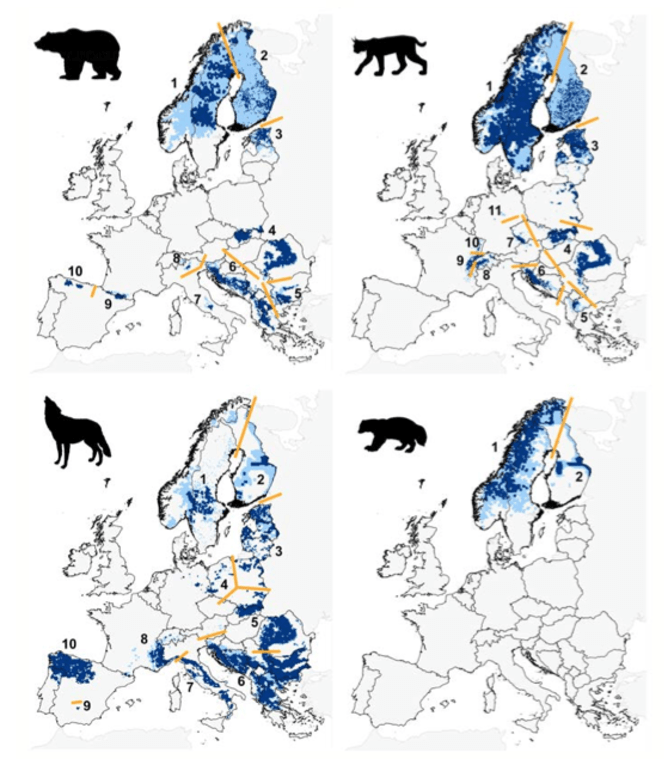

No bears in Britain – distribution of Europe’s large carnivores in 2011. Sciencemag

“Obviously it will be different for different groups of people,” said Rust. “So trying to work out how many we want is going to be very tough.”

Large carnivores can be costly to sustain. In an effort to gain sometimes reluctant acceptance of them, governments have set up various schemes, such as compensation for livestock killed or financial rewards for the number of predators in an area. Between 1992 and 1998, the European Union paid out €1.37m in compensation for livestock damage by predators.

“Carnivores can be troublesome neighbours,” said Chapron. “So we have conflict: we have conflict with livestock farming, hunters – it can be difficult to co-exist with predators.”

The study raises another question: the abandonment of agricultural land in parts of Europe may be good for carnivores – but, as Young says, the continent’s increased reliance on imported food suggests that: “as agricultural land increases in developing countries, it’s obviously going to reduce the capacity of animals such as carnivores in those countries to survive.”

So maybe the comeback in carnivores in parts of Europe is coming at a cost to wild animals in other parts of the world. But the key message of the study remains a promising one: there’s no need to choose between humans and wildlife – you can have both.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation.