These were mainly profiles of actors and others from Bombay’s film industry, people whom he had known personally when he was a scriptwriter in the city. After India’s partition, he left for Pakistan but soon ran into trouble with the authorities because he was marked as a “most dangerous progressive”. Broke and desperate, he turned to writing for popular journals, drawing upon his own memories and experiences...

A collection of his pieces, translated into English as “stars from another sky”, has profiles of big stars like Ashok Kumar, Noorjehan and Naseem Banu, long forgotten actors like Rafiq Ghaznavi and Kuldeep Kaur and one journalist – Baburao Patel.

The name will mean nothing to a modern reader but at one time, for a long stretch of nearly twenty years, Baburao Patel was the most feared journalist in the Indian film industry. Editor of Filmindia, a monthly magazine, Baburao’s comments, by way of columns, film reviews and his hugely read Q and A section were followed assiduously by his fans. He received letters in the thousands from readers all over the world. Rarely has an editor had such a connect with his public as Baburao had.

“Baburao wrote with eloquence and power. He had a sharp and inimitable sense of humour, often barbed. There was a tough guy assertiveness about his writing. He could also be venomous in a way that no other writer of English in India has ever been able to match,” wrote Manto…

Just who was Baburao Patel? What made him and his magazine so well-loved and detested at the same time? Why, if it was such a popular magazine, with subscribers in India and even far-flung places like Fiji and Africa, did it wither away and then eventually fold up?

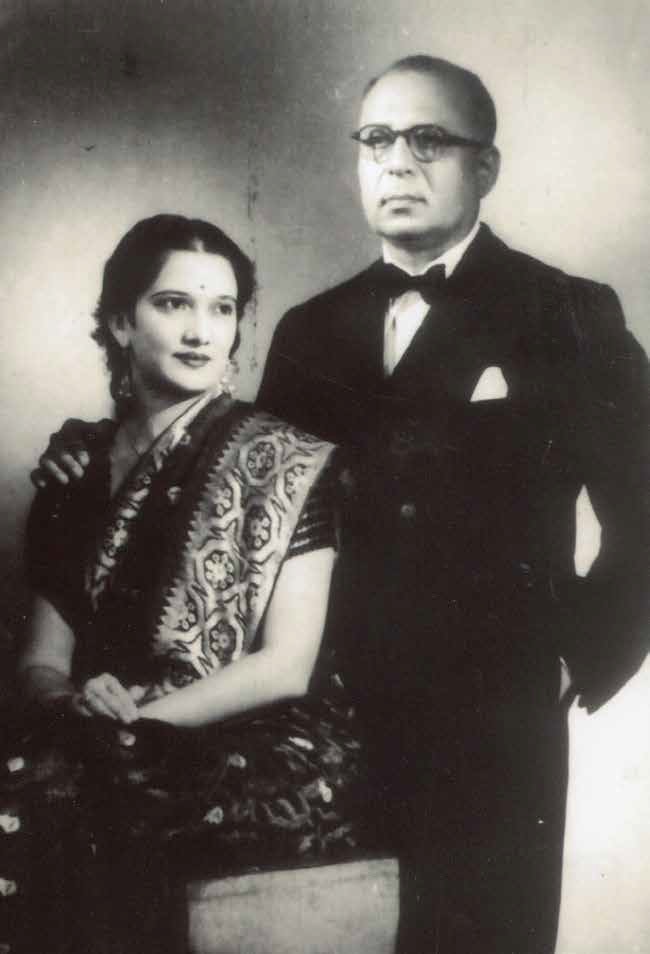

Sushilarani and Baburao Patel. Photo courtesy Estate of Sushila Rani Patel.

Baburao Patel was born on 4 April 1904, a happy confluence of numbers, in Maswan, a sleepy village about 100 kilometres from Mumbai, then called Bombay…Baburao’s father, Pandurang Vithal Patil, was one of the few lawyers from the Vanzara community and, indeed, in the village. The family name, Patil, got changed to Patel over the years, leading many to believe that he was a Gujarati. His mother, Jamuna, died when Baburao was just four, leaving him to be brought up by his uncle and father, who then remarried. The family shifted to Bombay and he was admitted to St. Xavier’s school. The young Baburao did not do well and left school without completing his matriculation. The lack of formal education always bothered him, and he had great respect for intellectuals and scholars, but it did not stop him from his pursuit of knowledge. Throughout his life he remained an avid reader of subjects ranging from Hindu philosophy and international politics to even alternative medicine.

After trying his hand at odd jobs, including selling cheap miracle cures, in 1926 Baburao joined a newly started film magazine, Cinema Samachar. Cinema was at its early stages and the need for a publication concentrating on this new, exciting medium was felt. No copies of this magazine remain, but it is believed that it came out in three languages – Hindi, English and Urdu. He then found himself drifting into the fledgling film industry as a scriptwriter and director. He made five films in the period between 1929-'35, beginning with Kismet (1929), Sati Mahananda (1933), then Maharani and Bala Joban (1935), and Chand ka Tukda (1933-'35)…

In 1935, Baburao joined hands with DN Parker, who owned New Jack Printing Press... The magazine, called Filmindia, was launched as a monthly in April 1935, at a price of 4 annas (annual inland subscription was Rs 3 and foreign subscription priced at Rs 5). It was printed on high-quality art paper and the cover was hand-painted, showing Nalini Tarkhud – an actress and novelist whose film Chandrasena, directed by Shantaram, is advertised inside… Inside, a lot of space was devoted to art plates of the stars of the time and scores of stills from the latest films.

The contents page not only listed what was inside, but gave an idea of what the editor’s viewpoint was: “American Producers and Anti-Indian Propaganda”, “Culture through the Eyes” were mentioned among the articles. The editorial said… “We don’t make any pretensions of having supplied a long felt want, but we certainly entertain an ambition of supporting this industry by honest journalism and constructive criticism of men and things and aspire to create a taste in our readers for Indian pictures (that) are representative of Indian culture and traditions.”

It was clear that upholding and promoting Indian culture was a very important part of Baburao Patel’s world view and Filmindia was to stake claim to be its custodian for years to come. As for honest journalism and constructive criticism, his detractors maintained that he had come nowhere near it but his fans felt otherwise through most of his career.

‘She has no face, figure or voice’

Baburao’s combative and take-no-prisoners style of writing becomes apparent right away. He wrote most of the magazine himself and certainly did the reviews, which he said would never be influenced or prejudiced by advertisers or by others. Advertisers who did not like this policy were welcome to stop their ads, he declared.

His review for the film Desh Dasi, produced by Ranjit Movietone, said it was a story “like an old pair of trousers made serviceable by bright and coloured patches”. Continuing in his colourful language, he said, “Direction of Chandulal Shah has certainly degenerated. An artiste at one time, in his hunt for money he has left his ideals far behind and in Desh Dasi we find him as the superintendent of the Mint rather than as a director.” He used the word “flopped” and ran afoul of the powerful Chandulal. Shah’s brother, Dayarambhai, told Parker frankly not to expect ads, but Parker stood by him.

The next review was of Fashionable India, where he was somewhat subdued in his criticism, but did point out that one of the girls, Johra Jan, had “no face, figure or voice”. From what was to come in later years, this was extremely gentle and understated.

The magazine was selling and subscribers were queuing up, but Baburao was broke – he became the first person in his family in “500 years” to go bankrupt. Getting out a magazine with no staff was not easy and Parker was lax with paying salaries. Baburao wrote of how his wife Shireen managed to feed the entire family, consisting of the couple and four kids, on “one rupee”. The editor had to take up assignments to write ad copy for films on the side, which brought in some income…

The issue has announcements of films that were in the cinemas as well as being produced at the time. Some of them include Painted Sin, Bahar-e-Suleimani, Orphans of Society and Mumbaya ki Sethani....

The ads are equally appealing to anyone interested in that period. Forthcoming films that are advertised include Toll of Love (S. Baburao, Shamrao, Zohra), Josh-e-Watan, After the Earthquake and the “first ever” detective thriller, Night Bird.

But it was his column “Bombay Calling” (written under the pen name “Judas”) that seemed the most promising. Full of gossipy snippets, it wrote about the general shenanigans of industry denizens in an entertaining way. “All these Bengalees have committed a great mistake in coming down to Bombay and create [sic] a new graft of culture in our industry. I do not think they have been received well and in fact some of them have been grossly insulted.”

He wrote about film production companies that were mere letterheads, fights between stars and directors, and shady producers who bought a car and acquired a pretty girl to impress financiers. It was no coincidence that film studios were far away from the city, because it offered a chance to the financier to offer a lift home to the heroine, he said mischievously.

The column ended with a note: “Dear Reader, if you have enjoyed these Tit-Bits write to us so and we shall put some more spice and pepper and serve you another plate next time.”

Bullets over Bollywood

There was not much competition in the market, except for some Urdu magazines in Lahore. But mainstream newspapers did have film reviewers, who eschewed gossip but were taken seriously by the industry.

One of them was Khwaja Ahmed Abbas. Abbas, who was to become famous later on for his scripts for Raj Kapoor, including Awaara, Shri 420 and Bobby, was then working for Bombay Chronicle and was a film critic. He had recently visited Hollywood and was a fan of European cinema, and thought of himself as a kind of superior film buff. Hindi films were below his tastes and he let it be known through his columns.

Shantaram’s film Aadmi (1939), however, impressed him and he dashed off a long review, praising it for being a “textbook on cinematic realism” and comparing it to the works of masters like Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Erich Von Stroheim. The director asked to see this young man, writes Abbas in his autobiography, I am not an Island. “That meeting, and the seeing of the picture together (I had already seen it four or five times), led to a friendship between Shantaram and me, with Baburao Patel’s ebullient personality and super-ego providing a link between the self-taught middle-aged Maharashtrian director and the young man fresh from a brief visit to Hollywood who vainly thought that he had got the whole world film industry by the tail.”

Baburao asked Abbas to write for Filmindia. “I had a sneaking admiration for Baburao and his magazine—they were everything that I wasn’t. They were glossy, opulent, popular, they hit hard when necessary and (not infrequently) when not necessary, and thus came to be a model of the ‘sledge hammer’ style of film journalism.” Baburao offered him fifty rupees per piece and complete editorial freedom.

Together, writes Abbas, they carried on a campaign against “anti-Indian” films in general and Gunga Din in particular. Other writers joined in, including Bakulesh, Jamil Ansari, Jitubhai and Saadat Hasan Manto, “the quickest literary writer who wrote remarkable short stories and humorous articles, as well as film reviews, straight on his Urdu typewriter”. Jointly they also formed the Film Journalists Association with “Baburao as the (inevitable) president”.

When Baburao Patel went to Hollywood for his own tour in 1939, he left the magazine in Abbas’s hands, with strict instructions not to tamper with the “Question and Answer” and the “You Hardly Believe” columns. “Though we differed on the fundamental ethics of journalism, and sometimes even quarrelled, a strange love-hate relationship developed between us. Baburao trusted and respected my integrity, and I had a sneaking admiration for Baburao’s guts in writing the sort of things he did, which were always spiced with gossip and scandal, and [were] occasionally libellous.”

Abbas’s own writings in the magazine were full of earnestness and righteous anger, as he launched into one target after another. He pilloried Hindi producers for copying foreign films, attacked anti-India films and let loose against “bogus critics”: “Pity the poor film critic – There is too much competition from the Viceroy, Governors, National Leaders, Society Ladies and studio publicity managers.”

Yet there was a difference in styles between Patel and Abbas and, for that matter, critics from other publications; Patel stood apart from all of them. A journalist, Jamil Ansari, analyzed them in the magazine: “Baburao Patel—if his pistol misses the target, he knocks you down with the butt end of it;” “K.A. Abbas – Never commits himself, even to himself”; “Miss Clare Mendonca (Times of India): Studio's publicity-officer's dream come true.” It was a fairly apt description of each one of them. And over the next few decades, Baburao continued to use the butt end of his pistol to devastating effect.