I read Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland around the same time the rest of you did – unless you were born in the 1990s, in which case I’m not even sure you read anything published before 1970 – which is to say I had a gorgeous blue and gold copy with full colour illustrations, and so on. But originally, my Alice came from the pages of a crumbling second hand “omnibus of children’s literature” where the Walrus shared a page with Lear and the Queen of Hearts held up a flamingo half torn because the page was coming off.

I remember the feel of the embossed cover in my hands, because I was a fussy eater, I was encouraged to eat with a book (I think that might be why I can only watch TV now if I’m also playing Candy Crush at the same time, call it a pre-programmed multitasking thing.)

Wonderland, yes, but Alice, no

But Alice for all her charm was never my thing. Oh, I liked Wonderland and Through The Looking Glass well enough, but it was only years later that I was to recognise why I didn’t take to it as much as I was supposed to: the dream narrative, the magical realism, all literary concepts that hopped, skipped and jumped right over my head as a child who demanded real life even from literature.

A child’s world is filled with magic and imagination to begin with, and maybe I only speak for myself, but I liked my books to stay put and not stray all over the place. However, I was far more open to the world of Wonderland as a little girl than I would be now – mad tea parties and white rabbits that talked and cats that disappeared leaving only their grins was par for the course.

I even had two imaginary friends of my own, called Sarah and Gaurav who regularly promised to teach me how to fly, and in my head, the whistle of the night watchman on the street outside turned him into a patrolling penguin.

Alice for the 21st Century?

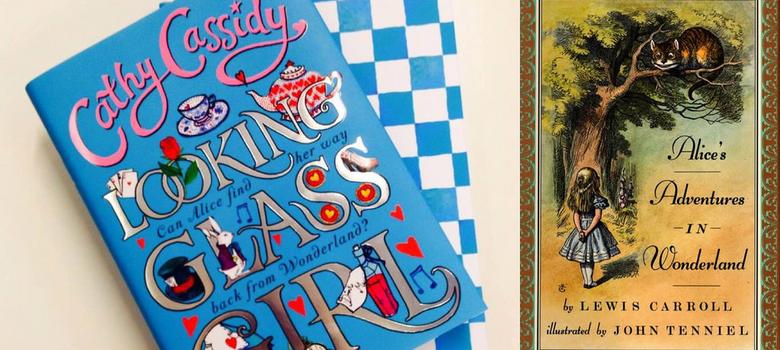

All this to say that I began reading Cathy Cassidy’s Looking Glass Girl with a certain amount of trepidation. Would her Alice be Disney’s blonde haired blue bowed waif? Or her Mad Hatter have Johnny Depp’s geisha mouth and wild red hair?

Neither, as it turns out. Looking Glass Girl is about that much loved trope in YA and kid lit, a girl who gets bullied.

Alice Beech, the titular character, joins a new school and her old friends promptly ditch her for the new more “happening” crowd. Sad and lonely, she drifts through most of the book wondering what went wrong.

Bullying is a common writing device for children’s literature authors – myself included as I work on my second young adult novel – and I got to thinking as I was reading it. What attracts us so much to the outside child, the one looking in?

Is it because that’s what we were like as children, everyone who grows up to be a writer today, or is it because in a child’s world, the biggest villain will always be the popular kids who make fun of the way you are? Does this mean the “popular kids” don’t read, or just that in every child there is an element of feeling like the person who no one really understands?

Cassidy is already a popular children’s author and this book – a hardback – has a cover that kids would love: pink and silver with embossed writing, and when you slip off the jacket, a plain checked book with no title that you could easily hide in your schoolbag and read during boring classes with no one being the wiser.

The characters are engaging too, but there are bits that I suspect Cassidy wrote just for herself, like the internal monologues of the mother or the doctor or the policemen, and those are quite a jarring break from the overall charm of the first person narrator.

Stretched parallels

But is it Through The Looking Glass? It is not. It is a reimagining, but there is a desperate attempt to put in parallels which you wouldn’t see for yourself.

Note to the author: if you have to explain “girls with Cheshire Cat smiles” in the blurb, then it’s probably not coming through very well in the book. Cassidy’s Alice has an accident and through her coma keeps imagining white rabbits and Tweedledum and Dee Esquire, but those bits of italicised prose take away more than they add to it.

Ultimately, should your kid – or you – read this book? I’m not sure. There are loads of other, better books about being an outsider and being bullied (for instance, The Outside Child by Nina Bawden, while not about bullying, has lovely soliloquys about this very fact).

There is also the original Alice, published 150 years ago, which is a childhood classic that should last the ages, whether or not you like it, just for the nonsense that goes on through the book, and because everyone should stay in touch with that wild, surreal inner self that it celebrates.

“We’re all mad here,” says the Chesire Cat in Wonderland. The problem with Looking Glass Girl is that it isn’t mad enough.

We welcome your comments at

letters@scroll.in.

I remember the feel of the embossed cover in my hands, because I was a fussy eater, I was encouraged to eat with a book (I think that might be why I can only watch TV now if I’m also playing Candy Crush at the same time, call it a pre-programmed multitasking thing.)

Wonderland, yes, but Alice, no

But Alice for all her charm was never my thing. Oh, I liked Wonderland and Through The Looking Glass well enough, but it was only years later that I was to recognise why I didn’t take to it as much as I was supposed to: the dream narrative, the magical realism, all literary concepts that hopped, skipped and jumped right over my head as a child who demanded real life even from literature.

A child’s world is filled with magic and imagination to begin with, and maybe I only speak for myself, but I liked my books to stay put and not stray all over the place. However, I was far more open to the world of Wonderland as a little girl than I would be now – mad tea parties and white rabbits that talked and cats that disappeared leaving only their grins was par for the course.

I even had two imaginary friends of my own, called Sarah and Gaurav who regularly promised to teach me how to fly, and in my head, the whistle of the night watchman on the street outside turned him into a patrolling penguin.

Alice for the 21st Century?

All this to say that I began reading Cathy Cassidy’s Looking Glass Girl with a certain amount of trepidation. Would her Alice be Disney’s blonde haired blue bowed waif? Or her Mad Hatter have Johnny Depp’s geisha mouth and wild red hair?

Neither, as it turns out. Looking Glass Girl is about that much loved trope in YA and kid lit, a girl who gets bullied.

Alice Beech, the titular character, joins a new school and her old friends promptly ditch her for the new more “happening” crowd. Sad and lonely, she drifts through most of the book wondering what went wrong.

Bullying is a common writing device for children’s literature authors – myself included as I work on my second young adult novel – and I got to thinking as I was reading it. What attracts us so much to the outside child, the one looking in?

Is it because that’s what we were like as children, everyone who grows up to be a writer today, or is it because in a child’s world, the biggest villain will always be the popular kids who make fun of the way you are? Does this mean the “popular kids” don’t read, or just that in every child there is an element of feeling like the person who no one really understands?

Cassidy is already a popular children’s author and this book – a hardback – has a cover that kids would love: pink and silver with embossed writing, and when you slip off the jacket, a plain checked book with no title that you could easily hide in your schoolbag and read during boring classes with no one being the wiser.

The characters are engaging too, but there are bits that I suspect Cassidy wrote just for herself, like the internal monologues of the mother or the doctor or the policemen, and those are quite a jarring break from the overall charm of the first person narrator.

Stretched parallels

But is it Through The Looking Glass? It is not. It is a reimagining, but there is a desperate attempt to put in parallels which you wouldn’t see for yourself.

Note to the author: if you have to explain “girls with Cheshire Cat smiles” in the blurb, then it’s probably not coming through very well in the book. Cassidy’s Alice has an accident and through her coma keeps imagining white rabbits and Tweedledum and Dee Esquire, but those bits of italicised prose take away more than they add to it.

Ultimately, should your kid – or you – read this book? I’m not sure. There are loads of other, better books about being an outsider and being bullied (for instance, The Outside Child by Nina Bawden, while not about bullying, has lovely soliloquys about this very fact).

There is also the original Alice, published 150 years ago, which is a childhood classic that should last the ages, whether or not you like it, just for the nonsense that goes on through the book, and because everyone should stay in touch with that wild, surreal inner self that it celebrates.

“We’re all mad here,” says the Chesire Cat in Wonderland. The problem with Looking Glass Girl is that it isn’t mad enough.