But there is only one actor who once he became a lead has never relinquished that position. That, according to a new study of how interactions in Bollywood can predict actors’ success, is Amitabh Bachchan.

“None of our theories work for Amitabh Bachchan,” said Sarika Jalan, an associate professor at the Indian Institute of Technology in Indore, who led the study. “We cannot define whether he is a supporting or a lead actor because he always comes out as the lead and defies all predictions and theories. He is very different from others.”

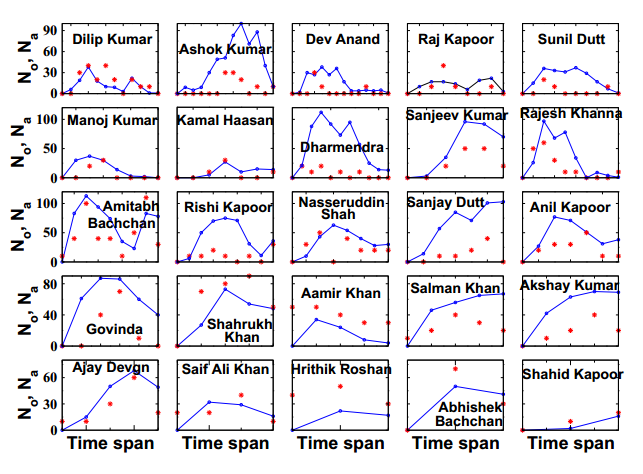

Plot of individual overlaps of lead male actors and their Filmfare award nominations across time. Image from PLoS used with author's permission.

All leading actors work in a certain limited number of projects, which enables them to remain successful, according to the paper, Uncovering randomness and success in society, which Jalan co-wrote with three PhD students, Camellia Sarkar, Anagha Madhusudanan and Sanjiv Kumar Dwivedi. Supporting actors, on the other hand, tend to work in either too many films, or too few, which then affects their careers.

Amitabh Bachchan, however, has worked in far more films than any other lead actor, but still manages to remain on top. He is the only exception to their theory.

Jalan and her team use the number of Filmfare awards an actor has won as a measure of success, largely because it has been around for so long. The first Filmfare award was in 1953 and it has been awarded regularly ever since.

The paper applies the random matrix theory, which originates in nuclear physics, to the social structure of Bollywood. The random matrix theory, which is about 60 years old, postulates that all complex systems, from brain cells to neurons, share some common property.

Others have applied the theory to interactions on Facebook and Twitter, but this, according to Jalan, is the first time anyone has applied random matrix theory tool for a real world social system.

“People have done work with Facebook or Twitter before, but these are small frameworks,” she said. “They do not represent everyone. Bollywood reaches everyone because everyone from rickshaw drivers to millionaires goes to see these movies.”

The team took four months to compile all the data, which ranges from 1913 to 2012 and covers almost 9,000 films. They used Bollywood film listing websites as their sources and then compared and culled out the duplicated names. They compared the cast lists of all the films. Lead male actors were classified as the ones who were billed first, but due to gender biases in billing, they found it difficult to similarly classify lead female actors.

Each actor is a node. If two actors have worked in the same movie, they are considered to be connected. The team then used a code to map connections over a period of time.

Jalan and her team realised that those who were most successful, or were able to maintain their careers over a longer period of time, were those who maintained their interactions at a certain level.

At present, the industry has 3,611 actors, with over 10,000 nodes and 60-70 lakh connections between them.

Films as social change

The team’s most striking finding was that the network of connections also seems to respond to social changes, particularly with the period from 1963 to 1967 and from 1948 to 1952.

“Our results do not apply to only these periods,” she said. “These were the years when India was at war. “When we found these periods were not fitting, we realised that India faced war in those periods, which led to a lower financial security.”

The study also reflects changes in Bollywood itself. In 1998, as producers and directors were going through major financial shortages, the government declared that Bollywood would be considered an industry. This meant they would be eligible for loans from banks.

“In early years, the networks were very random and you could not predict who would be successful in the next period,” said Jalan. “But once Bollywood got the status of an industry in 1998, the size of the network increased and there was also an increased regularity in behaviour.”

Jalan has not yet, however, extended her predictions to the next few years, so she does not know who will be the next round of successful actors. The study also does not look at more local variations in Mumbai to see how that might affect the popularity of actors.

Statistically speaking, Jalan believes that the industry is particularly strong as complex systems go.

“We might have economic problems and wars, but the industry never collapsed,” said Jalan. “Some amount of randomness is always necessary to keep the system robust. Too much control leads to fragility.”