If we actually had better things to do than gawk at celebrities, there would be no Elle Style Awards, and Zellweger wouldn’t walk the red carpet at such events. Strange how those who flourish within an industry based substantially on physical appearance can turn sanctimonious about the media’s preoccupation with physical appearance. But American celebrities faced with questions about their changed looks have no refuge except sanctimony because their culture worships two contradictory deities: the goddess of nature, and the goddess of youth and beauty. The great lie the culture lives by is the pretence that both divinities can be served equally. Women face the contradiction most keenly, since youth and attractiveness are tied more closely together in females than males. It is a deeply unfair, even tragic, state of affairs, but then nature, far from being the benevolent deity imagined by theologians of the New Age, is a cruel goddess, as this passage from Samuel Beckett’s Endgame makes clear:

HAMM: Nature has forgotten us.

CLOV: There's no more nature. …

HAMM: But we breathe, we change! We lose our hair, our teeth! Our bloom! Our ideals!

CLOV: Then she hasn't forgotten us.

The trick

The religion of nature forbids cosmetic surgery, but the cult of youth and beauty eventually demands it. The trick, which Zellweger failed to learn, is to betray nature in such small increments that the betrayal stays secret. This week, I finally watched Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider, in which Tabu played the protagonist’s mother, a role that has become familiar territory for her in recent years. Needless to say, male stars much older than her continue to play romantic leads. Tabu was always unconventional looking by the standards of Indian films, and always much more than blockbuster eye candy. She even let her under-eye bags show, and I admired her for it. There are no bags under her eyes in Haider. Perhaps it is careful make-up; or perhaps the goddess of youth and beauty has demanded surgery even of her. At any rate, it will remain secret, because nature, if betrayed, has been betrayed with finesse.

Unlike the United States and India, there are nations that owe little allegiance to the cult of nature. South Korea appears to be one of them, and, as a consequence seems not to taboo going under the knife. They say 5% of American women have opted for cosmetic surgery. The figure for South Korea is a staggering 20%. Not only do South Koreans, particularly women, change the way they look, they often change radically, and seem to do it without Ship of Theseus-type existential angst (I refer to the parable, not the film). The most common change they make is to their eyes, in order to obtain what they call a double eyelid. The procedure, known as blepharoplasty, is one that Renée Zellweger almost certainly had. It widens the eyes and creates a creased upper eyelid by removing or reshaping fat and skin, particularly the epicanthic fold characteristic of East Asian eyes.

Iran's nose jobs

I can’t end a column about plastic surgery without discussing Iran, where I discovered a refreshingly positive attitude to cosmetic surgery, specifically to nose jobs. Many Iranians possess disproportionately large noses, and with hijab compulsory, women in particular find that one organ consumes too much precious acreage. The solution is rhinoplasty, which is incredibly popular. Any tourist can tell it’s common because there are people walking around everywhere wearing post-operative masks. No shame-faced withdrawal from the public among Iranians; they feel no need to hide their betrayal of nature because they owe nature no fealty.

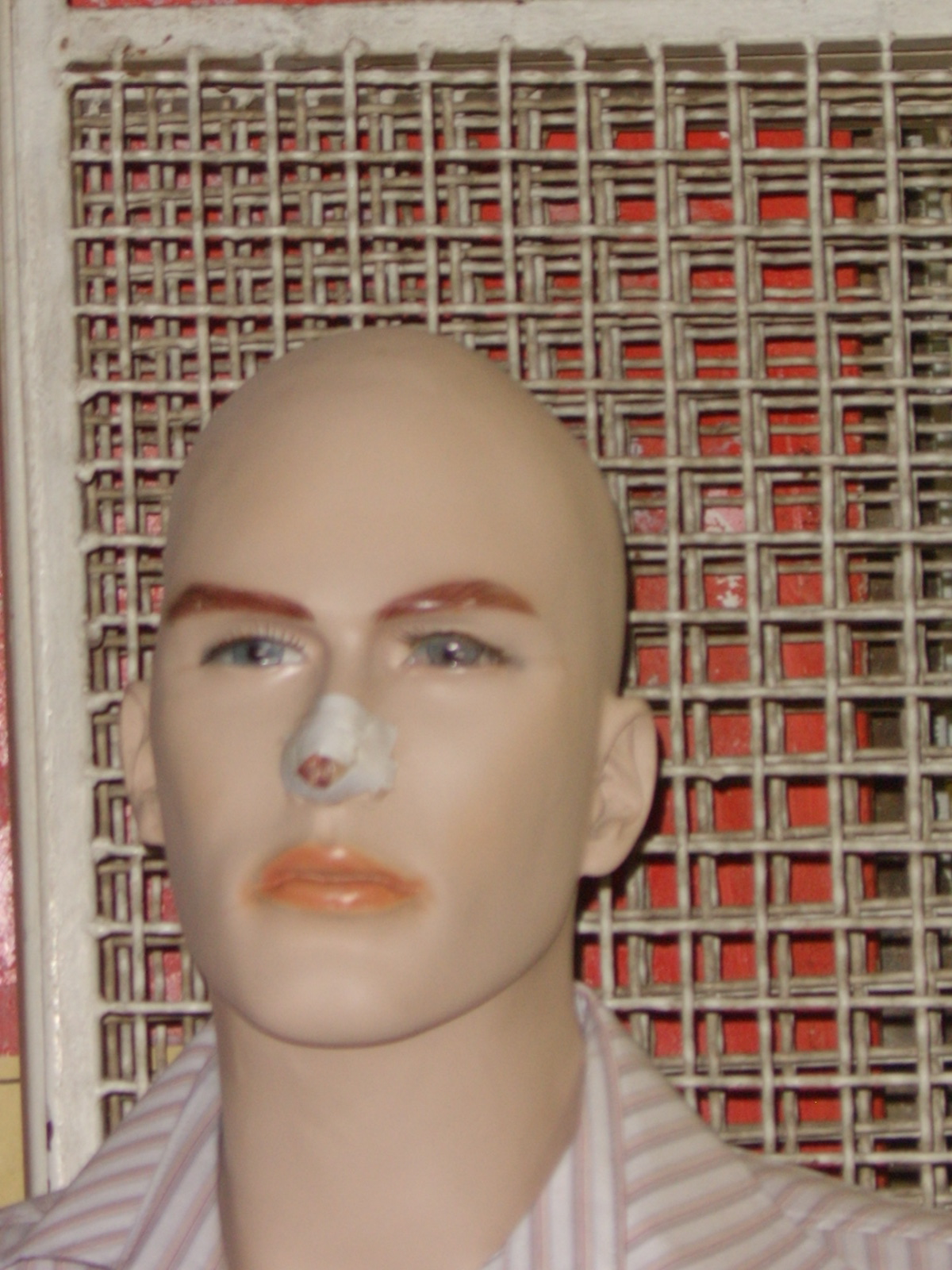

Since surgery is expensive, rhinoplasty has become a status symbol, to be flaunted rather than covered up. The final stage in the healing process, a simple piece of plaster stuck across the new, finer nose, is a fashion statement among youngsters in Shiraz and Tehran. And, just as Rolexes and Louis Vuitton handbags spur knock-offs, Iranians have invented the knock-off nose job bandage: worn by wannabes who have not had any cosmetic surgery done. You want the polar opposite of Renée Zellweger’s question dodging? I found it in the heart of the axis of evil in Esfahan, on the nose of a storefront mannequin who was apparently at the penultimate stage of post-rhinoplastic healing. It cured me of my residual loyalty to the cult of nature.