On a bracing summer morning in Lucknow last week, after a brief round of haggling over fares, I sat in Raju Yadav’s auto rickshaw, and within a few minutes, he had given me an outline of his life: as a child, he had run away from his village near Haldwani to come to Lucknow, where he worked in a hotel, graduated to riding a cycle rickshaw and finally learnt to drive. He is now married and his daughter is old enough to go to school. But he can't afford to send her to an English-medium school because his auto is a hired one. Of the Rs 800 he earns on an average every day, Rs 300 goes to the auto owner.

The conversation soon turned to elections, as we headed for Ambedkar Park, the sprawling and controversial memorial built by the former Bahujan Samaj Party government. With its larger-than-life sandstone elephants and towering statues of dalit leaders, the park has been compared with London’s St Paul’s Cathedral, Cambodia’s Angkor Wat and Egypt’s Karnak Temple. “Only the pyramids are starker; only the Parthenon itself more monumental,” wrote The Financial Times, in a report that tried to understand why the government of one of India's poorest states would spend billions of rupees on it.

Who are you voting for, I asked Raju.

"I vote for Behenji," he said.

BSP leader Kumari Mayawati is respectfully called Behenji by her followers.

But wasn't that unusual for a Yadav, I asked. Yadavs are traditionally known to vote for Samajwadi Party, the party currently in government led by Akhilesh Yadav.

"I vote for Behenji because she gave me a roof of my own," he said, "while Akhilesh cannot even give me electricity."

What do you mean, I asked.

"Chaliye hum aapko dikhaate hai."

The sandstone elephants had come into view but we headed off in another direction.

***

In the five years of Mayawati’s government in Uttar Pradesh from 2007, the massive memorials she erected in the heart of Lucknow drew steady attention. But the small homes she built for the poor on its outskirts went largely unnoticed.

Launched in 2008, the Manyawar Kanshiram Shahri Garib Awas Yojana scheme aimed to construct 100,000 low-cost homes for the urban poor every year. Of these, half were reserved for scheduled castes and tribes.

At the time Mayawati was voted out of power, the first round of construction was over – more than 90,000 homes had come up in towns and cities across the state - and a second and a third round were underway.

Within two months of winning elections in 2012, the SP government scrapped the scheme. No new construction would be undertaken, it announced, once the existing construction was wrapped up.

Work was completed on half a dozen housing colonies in Lucknow in the summer of 2013. People moved into their homes, only to find there was no electricity.

"There are poles on the road but there is no connections in our homes. Summer is coming soon. How will we manage?" Kunti, who lived in the Kanshiram colony in Chinhat, a semi-urban area on the eastern edge of the city, had wasted no time in briefing me when I got off the auto.

As we had turned into the colony, Raju’s auto had driven past neat rows of four-storey buildings, painted in white and blue, with handbills of a Mayawati rally and a computer institute stuck on the walls. We stopped near a small candy shop made of wood and plastic, where Kunti sat with her husband, Ram Narayan Gautam. A mistri, he worked in people’s homes, and lived from day to day on uncertain wages.

“Zindagi humari poori guzar gayi madiye mein. My life went by under a tent,” said Kunti. Before they had moved here, the dalit couple and their two children lived in Daliganj, in the centre of the city, in a shanty town.

How did they find a house here, I asked them.

In response, Ram Narayan pulled out a small tattered notebook from his pocket. He opened it to a torn page where a number was scribbled against the name of Manani Mukhyamatri'. Honourable chief minister.

“This is Behenji’s number. Unke saath jo baithate wo khud hi uthate hai. Her assistant picks it up.”

It was an extraordinary story: A relative who worked for the BSP had given Ram Narayan the number, and one time when they had trouble in their shanty town, he had called on it. The man at the other end, he claimed, told him “Jhopdpatti mein mar rahe ho, kahe na colony paas karwa lete. Why are you dying in the shanty town? Why don’t you apply for a home in the colony.”

The same evening, an officer was at their doorstep. “He came at the time we had sat down for dinner,” said Kunti. “He took pictures of our house. And later we came to know our name was on the list.”

"Behenji was very clever to put the names of the poor beneficiaries on the internet," said Ram Narayan. "Else the next government would have eaten up our homes.”

The home itself was matchbox sized. Two tiny rooms, each not bigger than a double-bed.

“Here's the bathroom," said Ram Narayan, as he showed me around with a sense of quiet pride, "and here's the toilet”.

What about water supply, I asked.

"No problem at all,” he said with much emphasis. “We get water twice a day. For at least an hour.”

Grateful for the government’s small mercies, their only grouse was the lack of electricity.

“We went and met the officials who asked us to wait until the elections,” said Ram Narayan. “Depending on who wins, they said, we would either get or not get the connection.”

***

"We are currently busy with elections," said Raj Shekhar, the district commissioner of Lucknow, when I called to ask him about the lack of electricity supply to the Kanshiram colonies. "You should check with the electricity supply authority."

Officials at the authority's office did not respond to calls.

In earlier media reports, the officer in charge of the housing projects has blamed electricity officials for demanding money for providing connections, while electricity officials have said the financial condition of the board did not permit free connections. Meanwhile, on January 27, before the crisis could be resolved, the Akhilesh government issued an order asking officials to freeze spending under the scheme.

***

"2 June 1995. Grih Aththi Kaand. The Guest House episode.”

I had asked Mahesh Satyawadi, a middle-aged social worker who lived in the colony at Gheru, 20 kms from Lucknow on the Kanpur road, why the Kanshiram housing colonies were being denied electricity.

In response, he evoked the events of 1995, when a mob of SP workers stormed a government guest house in which Mayawati was staying, intent on punishing her for withdrawing support from their government. The police managed to reach just in time to rescue her from the mob. This was the start of a deeply acrimonious politics in the state, which the residents of the Kanshiram colonies believe explains the present government’s khundas (resentment) towards them.

“You have personal scores to settle but what is the fault of poor people? Do only BSP supporters live in these colonies?” said Satyawadi.

On cue, the nameless crowd gathered around us began to break up into individuals with distinct identities.

“Ali Ahmad.”

“Sanjay Agarwal.”

“Horelal Pasi.”

“Manoj Yadav.”

“And there’s a Mishra, who sells chaat,” said Satyawadi, who identified himself as anusochit jaati.

Raju had introduced him as netaji, but Satyawadi clarified that he was not a politician. “I am a social worker,” he said, walking me up to his home on the fourth floor, to show me all the letters, press clippings and RTI documents that he had collected during his struggle to first get homes and then electricity for the people of his neighbourhood.

"I sat on a hunger strike in 2008, as soon as the scheme was announced, because I felt that the homes would be taken away by others, and the deserving would be left out," he recalled.

“I have been working for the community for more than 20 years. But I did not take up a political post isliye kyunki humein dalali nahi karni (because I don’t want to be a broker).”

As he pulled out papers from a broken suitcase, I noticed an old BSP letter dating back to 1996.

“The party workers who have reached high positions are all known to me. Ram Avtar Mittal. Mewa Lal Gautam.” Reminiscing of the early days of the party, he said, “That was a different time. Dalits were being oppressed, the party was working for dalit uplift, and people like me volunteered for it. But things changed. Kanshi Ram died. Party leaders became obsessed with making money. They forgot the old slogan, Tilak Tarazu aur Talwaar…”

In the elections of 2007, the slogan that attacked the symbols of the upper castes, and by extension, the caste system, was replaced by one that embraced them: Haathi nahi , Ganesh hai Brahma Vishnu Mahesh hai.

This, coupled with the rising trend of wealthy candidates being favoured over long-time workers, had led many old timers to quit the BSP.

Chastened by its defeat in 2012, the party appears to have made an attempt to strike a balance this time. In Lucknow, Nakul Dubey, a wealthy Brahmin leader and a former BSP minister, is in the fray against the BJP President Rajnath Singh. In Mohanlalganj, the outer Lucknow constituency in which the Kanshiram colonies fall, the party has fielded RK Chaudhary, a founder-member of BSP, who left the party in 2001, only to return to its fold last year.

Would he be voting for Chaudhary, I asked Satyawadi.

“I would vote for whoever has a clean image.”

As we went back downstairs, the crowd gathered on the road had grown larger and more restive.

"Please write: Life here has come to a standstill. Children's education is suffering. Crimes are taking place with alarming frequency. We need to get electricity with immediate effect," said an old woman, Uma Sheel Messi, who identified herself as "a Christian and a former president of the woman's wing of the CPI(ML)".

"We will march to Parliament if the government does not give us electricity," she said, adding that she was hopeful there wouldn't be a need for that. "Once our sister Mayawatiji wins this election, she would set things right."

But the coming elections were for the Lok Sabha and not for the state assembly, I said.

"So what. They will impact even the state."

Since when has she been voting for Mayawati, I asked her.

“From the time Mayawati gave me a house. Wo humari humdard hai. Hum unke humdard hai. Only she can come and give us electricity."

But what if the SP government gave them electricity before the elections – would she vote for them?

She paused. The answer lay in her confusion.

But for the dalits in the crowd, there was no such confusion. An old man, Vinod Kumar Gautam, broke into the slogan: “Vote padega haathi pe chahe goli lagagi chaati mein. Shoot us in the chest but we will still vote for the elephant."

***

As we drove away, I asked Raju who would he be voting for.

"It all depends on the electricity situation," he said. "If there is no electricity, I would vote for Behenji."

And if there is electricity, would he vote for SP?

"Why not. Whoever does good work should be rewarded...Waise people nowadays are talking a lot about Narendra Modi. They say he is forming the government in Delhi.”

Does that mean he is considering voting for the BJP?

"Let there be light first. Only then would we know who is good and who is bad."

***

"We have always voted for the BSP. Whether it wins or loses," said Kunti.

"Have you heard the name of Narendra Modi?" I asked her.

“Even if I may have heard, I have forgotten. I keep forgetting names. But he would know. Ask him," she said, pointing to her husband.

But Ram Narayan was too busy to listen. He was scribbling down a number on his tattered notebook.

It was a number advertised on a poster of the Association for Democratic Reforms pasted on the back of Raju's auto.

The poster exhorted people to give missed calls to the number if they wanted to know more about the assets of their local candidate.

While the number was in bold, the rest of the message was in fine print. Ram Narayan had missed reading it.

"Kabhi zaroorat padegi to batiyaenge to kuch na kuch to fayada milega. If a need arises, we would call, and surely there would be some benefit," he said.

His trust and confidence stemmed from the picture on the poster: A man with an intense look on his face stood with folded arms.

"He has been coming on TV and asking people about their problems. People have been taking their problems to his baithak. Even officials come there. There is no electricity here, but at our earlier residence, we used to watch him with great interest. Inko hum bahut chav se dekhte the. Now that we have his number, we can call and tell him about our problem."

"Would you vote for him if he stood for elections?"

"Of course. Bilkul."

"What's his name?"

"Oh, I keep forgetting names," said Kunti. "Kya naam raha inka...haan...Aamir Khan."

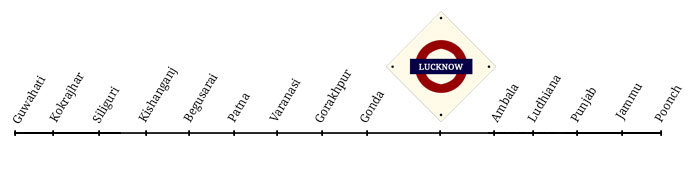

Click here to read all the stories Supriya Sharma has filed about her 2,500-km rail journey from Guwahati to Jammu to listen to India's conversations about the elections – and life.