In March 2012, the Samajwadi Party won the Uttar Pradesh assembly elections, ending five years of Bahujan Samaj Party rule.

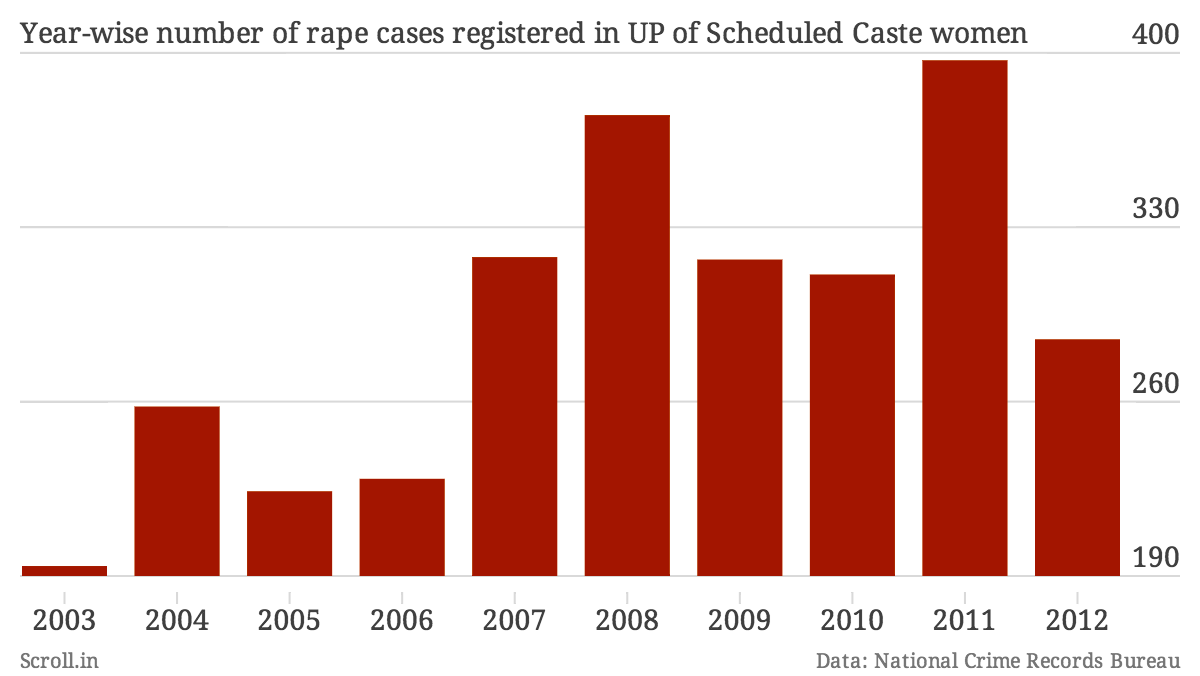

Among other things, the regime change was reflected in the state's crime statistics. The number of rape cases of Dalit women dropped from 375 cases in 2011 to 285 cases in 2012.

A drop in the number of rape cases usually shows a government in good light. But in Uttar Pradesh, the interpretation is different: it isn't the actual number of rapes of Dalit women that may have gone down but the number of cases filed by the police, say scholars and Dalit activists.

"Under Mayawati, the police had strict instructions to file a case whenever a Dalit woman came to complain," said Badri Narayan, professor at the GB Pant Social Science Institute, Allahabad. The increased responsiveness of the police could have led to a rise in the number of cases filed during the BSP regime, he says.

As the chart shows, there is a striking difference in the number of Dalit rapes registered under the SP and the BSP. In 2002-’07, when the SP was at the helm of power, the number of rape cases ranged between 194 in 2002 and 258 in 2004. In 2007-2012, with the BSP in government, the number rose to a high of 397 cases in 2011.

Another possible explanation for the rise in the number of Dalit women rape cases during the BSP regime, says Narayan, could be that Dalits faced a caste backlash from Yadav men who were upset with the shift in political power and wanted to re-establish their social dominance.

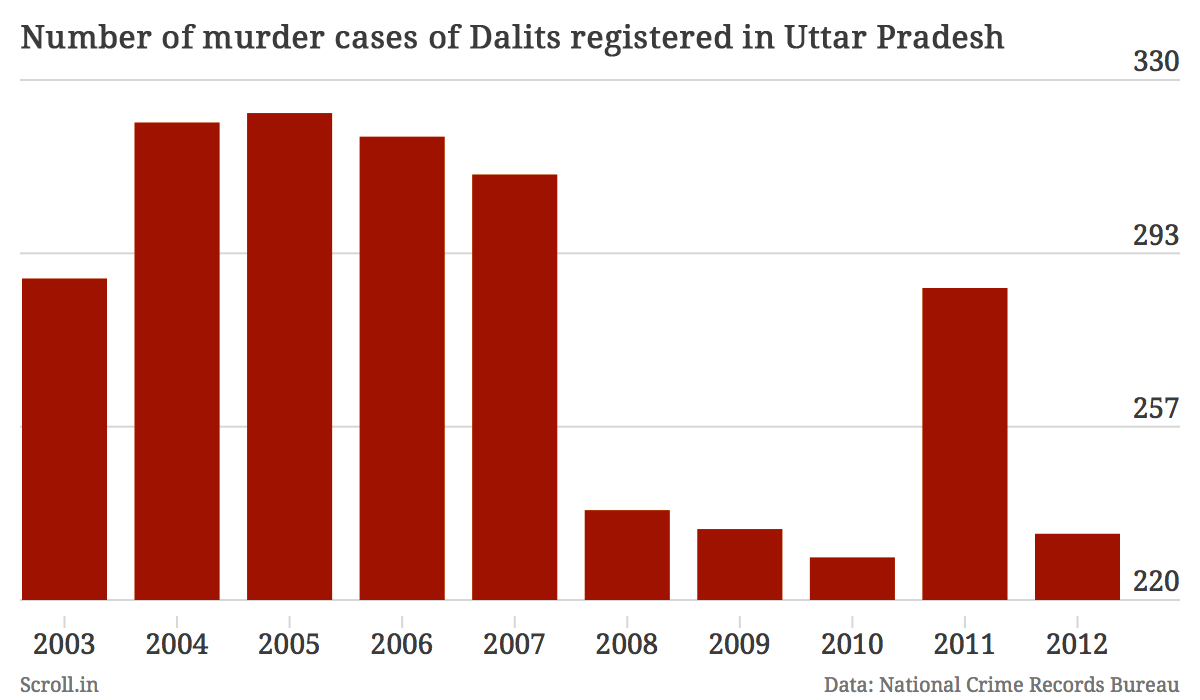

However, this argument is weakened by the decline in the number of Dalit murders during the BSP regime. Unlike rape cases, murder cases are hard for the police to ignore, or keep out of the records. More Dalits were killed during the SP regime as compared to the BSP regime, which indicates the level of violence faced by the community declined under the BSP.

With the SP back in power, the police has gone back to the old ways of ignoring complaints by Dalits, says Ram Kumar, Dalit activist and founder of the Dynamic Action Group. "The change in power at the top is instantly felt at the grassroots in Uttar Pradesh," he said.

With the BSP failing to win a single seat in the recent Lok Sabha elections, dominant castes like the Yadavs would feel "emboldened to carry out more attacks on Dalits", he added.

In Badaun, the evening the two girls went missing, the policemen, Sarvesh Yadav and Chatrapal Singh, refused to file a complaint. When the girls were found in the morning, they refused to go to the crime scene. They threatened the kill the families if they insisted on filing cases, the Indian Express reported.

Although the girls belong to a community which is not listed as a Scheduled Caste, Kumar said that their families, in conversation with reporters and activists, have identified themselves as Dalits.

"They belong to a caste group listed under 'most backward caste'," said Badri Narayan. "The social confrontation is no longer between upper castes and others. It is between SCs and MBCs on the one hand and Yadavs on the other.”

Unlike the Yadav-led Samajwadi Party, which is pointedly antagonistic to Dalits, the upper caste- dominated Bharatiya Janta Party has long been attempting to woo them.

The number of Dalit rape cases registered was consistently high between 1997 and 2002, when the state was ruled by the BJP. In fact, the highest number of Dalit rape cases – 412 cases – was registered in 2001. This was under the chief ministership of Rajnath Singh, the upper-caste leader who is currently India's home minister. This could either show upper caste assertion over Dalits, said Narayan, or a well-functioning police force that did not overlook the complaints of Dalits.

In the recent elections, the BJP is believed to have won a considerable chunk of votes among both SCs and MBCs. However, senior party leaders failed to show up in the village in which the Dalit girls were murdered, while BSP's Mayawati made a visit. Political observers believe it is a sign of BSP trying to wrest back support among the lower castes.

Ram Kumar, the activist, sees the portents of increased caste violence in the state in the run up to the 2017 assembly elections. "The only good news,” he said, “is that Dalits and lower castes are ready to die but not without a fight."

We welcome your comments at

letters@scroll.in.

Among other things, the regime change was reflected in the state's crime statistics. The number of rape cases of Dalit women dropped from 375 cases in 2011 to 285 cases in 2012.

A drop in the number of rape cases usually shows a government in good light. But in Uttar Pradesh, the interpretation is different: it isn't the actual number of rapes of Dalit women that may have gone down but the number of cases filed by the police, say scholars and Dalit activists.

"Under Mayawati, the police had strict instructions to file a case whenever a Dalit woman came to complain," said Badri Narayan, professor at the GB Pant Social Science Institute, Allahabad. The increased responsiveness of the police could have led to a rise in the number of cases filed during the BSP regime, he says.

As the chart shows, there is a striking difference in the number of Dalit rapes registered under the SP and the BSP. In 2002-’07, when the SP was at the helm of power, the number of rape cases ranged between 194 in 2002 and 258 in 2004. In 2007-2012, with the BSP in government, the number rose to a high of 397 cases in 2011.

Another possible explanation for the rise in the number of Dalit women rape cases during the BSP regime, says Narayan, could be that Dalits faced a caste backlash from Yadav men who were upset with the shift in political power and wanted to re-establish their social dominance.

However, this argument is weakened by the decline in the number of Dalit murders during the BSP regime. Unlike rape cases, murder cases are hard for the police to ignore, or keep out of the records. More Dalits were killed during the SP regime as compared to the BSP regime, which indicates the level of violence faced by the community declined under the BSP.

With the SP back in power, the police has gone back to the old ways of ignoring complaints by Dalits, says Ram Kumar, Dalit activist and founder of the Dynamic Action Group. "The change in power at the top is instantly felt at the grassroots in Uttar Pradesh," he said.

With the BSP failing to win a single seat in the recent Lok Sabha elections, dominant castes like the Yadavs would feel "emboldened to carry out more attacks on Dalits", he added.

In Badaun, the evening the two girls went missing, the policemen, Sarvesh Yadav and Chatrapal Singh, refused to file a complaint. When the girls were found in the morning, they refused to go to the crime scene. They threatened the kill the families if they insisted on filing cases, the Indian Express reported.

Although the girls belong to a community which is not listed as a Scheduled Caste, Kumar said that their families, in conversation with reporters and activists, have identified themselves as Dalits.

"They belong to a caste group listed under 'most backward caste'," said Badri Narayan. "The social confrontation is no longer between upper castes and others. It is between SCs and MBCs on the one hand and Yadavs on the other.”

Unlike the Yadav-led Samajwadi Party, which is pointedly antagonistic to Dalits, the upper caste- dominated Bharatiya Janta Party has long been attempting to woo them.

The number of Dalit rape cases registered was consistently high between 1997 and 2002, when the state was ruled by the BJP. In fact, the highest number of Dalit rape cases – 412 cases – was registered in 2001. This was under the chief ministership of Rajnath Singh, the upper-caste leader who is currently India's home minister. This could either show upper caste assertion over Dalits, said Narayan, or a well-functioning police force that did not overlook the complaints of Dalits.

In the recent elections, the BJP is believed to have won a considerable chunk of votes among both SCs and MBCs. However, senior party leaders failed to show up in the village in which the Dalit girls were murdered, while BSP's Mayawati made a visit. Political observers believe it is a sign of BSP trying to wrest back support among the lower castes.

Ram Kumar, the activist, sees the portents of increased caste violence in the state in the run up to the 2017 assembly elections. "The only good news,” he said, “is that Dalits and lower castes are ready to die but not without a fight."