The decision lent an aura of purposefulness to the new government.

Black money had featured prominently in the public discourse in the run-up to elections. As part of its election campaign, the Bharatiya Janata Party had promised to bring back black money stashed away abroad.

But experts say that shorn of its popular appeal, the singular focus on foreign-held funds is misplaced. These funds represent only a part of the illegal economy of India. But how large or small are they relative to the rest of the economy?

The trouble estimating the size of the foreign-held funds

There are no available official estimates for the size of the illegal economy in India. In 2011, the government had asked three institutions – National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, National Council of Applied Economic Research and National Institute of Financial Management – to study unaccounted income and wealth in India. At least one of the three institutes has submitted its final report but the ministry has not made it public.

In the absence of an official estimate, the media in India usually falls back on this report published in 2010 by a Washington-based think-tank, Global Financial Integrity.

It estimated that between 1947 and 2008, Indians had transferred $213.2 billion of illicit money abroad. If returns at the rate of short-term United States treasury bills were added, the value of the cross-border illicit transfers rose to $462 billion.

"This is a huge loss of capital which, if it were retained, could have liquidated all of India’s external debt totalling $230.6 billion at the end of 2008 and provided another half for poverty alleviation and economic development," writes Dev Kar, the economist who authored the GFI report.

Extrapolating from a study done in 1982, Kar says, "The size of India’s underground economy should be at least 50% of GDP or about $640 billion based on a GDP of $1.28 trillion in 2008. This means roughly 72.2% of the illicit assets comprising the underground economy is held abroad while illicit assets held domestically account for only 27.8% of the underground economy."

This is misleading, says Arun Kumar of the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at Jawaharlal Nehru University. In this article in the Economic and Political Weekly, Kumar points out that Kar has compared the stock at the end of a period (illicit assets transferred over six decades) to an annual flow (the annual gross domestic product for one year). "It would have been better to present the annual flow of savings going out of India as a ratio of the annual GDP," he writes.

Taking illicit transfers as a ratio of GDP, Kar estimated that black money sent abroad on an average amounted to about 1.5%-2.2% of India’s annual GDP.

His latest report, published in December 2013, based on a different methodology, however, revises upwards the estimates of illicit outflows from India. Based on the revised estimates, the black money sent abroad comes to more than 4% of India’s GDP.

Why Mauritius is more important than Switzerland

But black money sent abroad is not the same as black money held abroad. Funds are moved out of India not to be stashed away in Swiss banks but to be brought back as foreign investment, said an official with an investigative agency who did not wish to be named. This is called "round-tripping".

In the case of India, this mostly happens through sham corporations registered in Mauritius. While the money comes back as investments, the earnings on such investments are not taxed in India because India and Mauritius have a double tax-avoidance treaty.

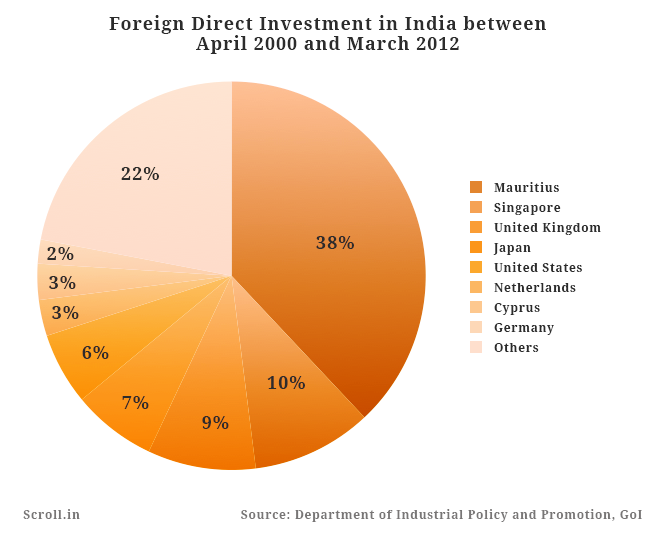

The primacy of the small island to the subcontinent is apparent from this statistic: Between 2000-2012, 38% of the foreign direct investment in India came from Mauritius, while only 6% came from the US. Mauritius accounted for $8,059 million of $18,286 million of FDI in India in 2012-'13.

If the government were serious about tackling the black economy in India, it would achieve more by closing the loopholes in the Mauritius route than by investigating Swiss bank accounts, said a government official on the condition of anonymity.

Real Estate is the big storehouse of black money

Where do the foreign funds that come into India go? A major destination is the real estate and construction sector. Between 2005 and 2010, FDI in India's real estate and housing market jumped 80 times. In 2010, nearly $5,700 million of foreign funds were invested in the sector.

The legal real estate sector accounted for nearly 11% of India’s GDP in 2011. But economists studying the black economy say the illegal real estate sector could be nearly as large, if not larger.

It is common knowledge that the sector generates black money when buyers and sellers of land keep the value of their transaction hidden from authorities to evade stamp duty. But as this ‘White Paper’ prepared by the Central Board for Direct Taxes in 2012 states, investment in property is also “a common means of parking unaccounted money".

Economists believe the infusion of black money has contributed to the sharp and sustained rise in land prices, which is making housing unaffordable for an overwhelming majority of Indians.

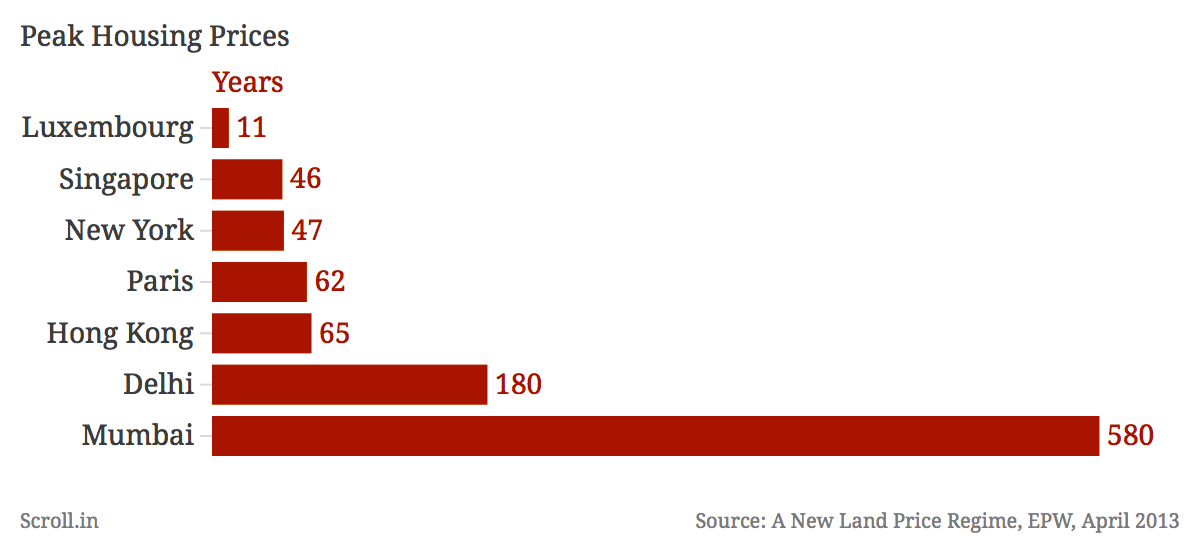

Urban land prices have risen five fold in the decade 2001-'11, writes Sanjoy Chakravorty, professor at Temple University. A citizen with an average national income would need to work for 62-67 years to buy property at the highest end of the market in Hong Kong, London, Tokyo and Paris. In contrast, it would take her 580 years to buy property at the highest end in Mumbai and 100 years to buy a modest 800 square feet flat at the metropolis-wide average rate.

In villages too, the prices of farmland have been showing puzzling spikes, as this report in the Economic Times said. It found that even villages far away from cities, highways and industrial projects were seeing inexplicably high land prices.

A CBDT report prepared in 2012 said, “Land and real estate are possibly the most important class of assets used for investment of black money.” Of the undisclosed incomes that the IT department detected in 2011-'12, the largest chunk – amounting to 40% – came from the real estate sector, PTI reported.

A private consultancy firm, Liases Foras, estimated that 30% of transactions in the property market in the first six months of 2012 went unaccounted. Speaking on the condition of anonymity, government officials said they believe the ratio is much higher – which means a larger portion of India’s GDP could be parked undisclosed in real estate deals within India than in secret bank vaults abroad.

There is another reason why cleaning up the real estate sector in India could be more fruitful than trying to bring back black money from abroad: despite signing hundreds of bilateral treaties to compel tax havens to share information on secret bank accounts, even the powerful G20 countries have failed to do so.

The second part of this series will look at the international debate on tax evasion.