Earlier in the month, on June 6, 18 Uttarakhand cops were convicted for killing an innocent man in custody in 2009. Of these, 17 were sentenced to life imprisonment.

The last major case of convictions in a case of police violence was in March 2013, when eight policemen were declared guilty 31 years after they shot 12 innocent villagers and one senior police officer in a fake encounter in Uttar Pradesh’s Gonda district.

These convictions are especially noteworthy because the Indian government’s official crime records claim to have just a handful of cases of human rights violations by the police.

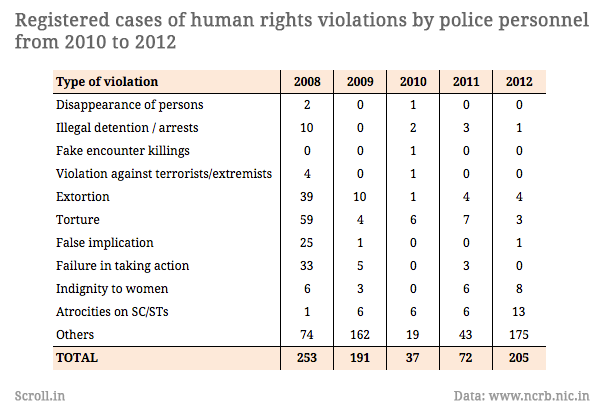

If the statistics provided by the National Crime Records Bureau are to be believed, there were just 205 cases of the police violating citizens’ human rights across all of India in 2012, just 72 cases in 2011 and a mere 37 cases in 2010.

The different types of violations listed by the NCRB include fake encounter killings, torture, extortion, illegal detention, atrocities against Scheduled Castes and even indignity to women. While very few cases are usually registered under these categories, there is an undefined category of ‘others’ under which most violations are registered.

According to these figures, there was one fake encounter case in India in the five years from 2008 to 2012, and just 22 cases of the police misbehaving with women during the same period. In fact, the many zeroes in NCRB’s tables on human rights violations by the police would make it seem like India is almost blissfully free of police atrocities. Here is a section of the NCRB data from 2010:

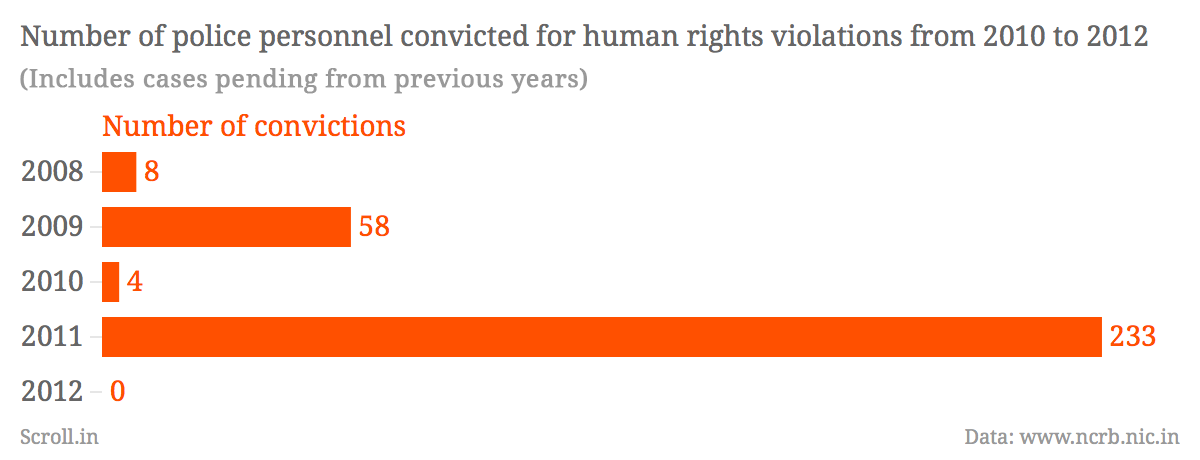

Meanwhile, conviction figures in these cases tend to fluctuate wildly. There are some years in which several pending cases are pronounced upon by the courts. In 2012, the last year for which the NCRB has published data, there were no convictions at all:

For lawyers and activists working in the field of human rights, these official figures are grossly unrealistic, but not surprising. The low numbers of cases registered against police personnel reflect the unwillingness of the force to implicate itself in these crimes, as well as the reluctance of victims, for various reasons, to complain about atrocities.

“If the police do not consider certain kinds of human rights violations as violations, they are not likely to register those complaints,” said Shabnam Hashmi, the founding trustee of Anhad, a non-profit human rights forum. Every time there is a terror attack, says Hashmi, several innocent youngsters are picked up and tortured in custody.

“It is done in the name of terrorism and the police do not recognise this as any kind of violation," she said. "If those youth are let off years later, they don’t go back to change the official statistics on police atrocities.”

On several occasions, however, victims do not even attempt to file cases against police personnel who violate their rights. At times, this is because of ignorance.

“Torture in custody is a norm across India, even for minor cases like theft,” said Mumbai-based social activist Vernon Gonsalves. “But the opposition to police torture is not very strong, because many people think men in uniform have the right to abuse them.”

Similarly, it is illegal for the police to detain a citizen for questioning for more than 24 hours, but people are routinely detained without arrest for days across Indian police stations. “The vast majority of people are unaware that this is illegal, and some are too scared of the police to complain,” said Gonsalves.

The fear of reporting police crimes is not unfounded. Gonsalves says that any complaint against the police is investigated by the officers of the same area, often at the same police station where the violation may have occurred. Complaints can be made to the State Human Rights Commissions, but most victims have neither access to good legal aid or knowledge about these commissions.

Despite this, several complaints against police crimes are directed to various Human Rights Commissions. In March, the chairman of the National Human Rights Commission stated that the NHRC received around 1.1 lakh complaints of human rights violations across the country in 2013, of which 34% were cases of violations by police personnel. This would mean that the NHRC received more than 36,000 complaints against the police in just one year, a figure that is completely incongruent with the average figures put out by the NCRB each year.

The problem, according to some activists, is the process of data collection itself. The NCRB gets its data by writing to the home departments of different states, who then write to the state police chief, who in turn asks for the data from each district. The coordination between different levels up and down this chain is very poor.

“The NCRB has no mechanism to verify the figures it receives, but it still has to publish them,” said Maja Daruwala, director of the non-profit Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. “The figures may therefore be doubtful, but they are all we have to rely on.”