Chief among them is the expected BRICS Development Bank, which some are rather grandly projecting as an alternative to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is going to be lobbying to place the headquarters of the bank in New Delhi, but even if it ends up in Shanghai, the five countries are expected to contribute up to $100 billion in the new project.

If you go by some of the more hyperbolic analysis, this week could see the beginning of the end for the Western financial consensus – built around the IMF and the World Bank – that has dominated the globe since the Bretton Woods agreement signed in 1944.

But if we are to build an all-new global architecture around this BRICS consensus, it’s worth taking a peek at the foundations. How did BRICS come together after all? The answer to that question happens to be another age-old wing of Western consensus: the New York-based investment bank, Goldman Sachs.

Jim O’Neill, an economist for Goldman, coined the term BRIC for a report in the Global Economic Paper series in 2001. Thanks in part to the catchy acronym, the grouping stuck, with the convenient addition of South Africa as the ‘S’ in BRICS, a few years later, representing the African continent.

That’s right, a cleverly titled Goldman Sachs report is the origin for what has now become an attempt to reshape the framework of the global economy.

But surely that is just coincidental, right? Goldman might have brought the five countries together, but there’s plenty that connects them. After all, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa all have great histories and an outsized influence on their neighbourhoods (a point that can only be made by ignoring other emerging countries – Mexico, Iran, Turkey, Indonesia and Nigeria – that could say much the same, albeit without the aid of a fun acronym). Certainly, as developing countries, they have much in common, right?

Let’s take a look.

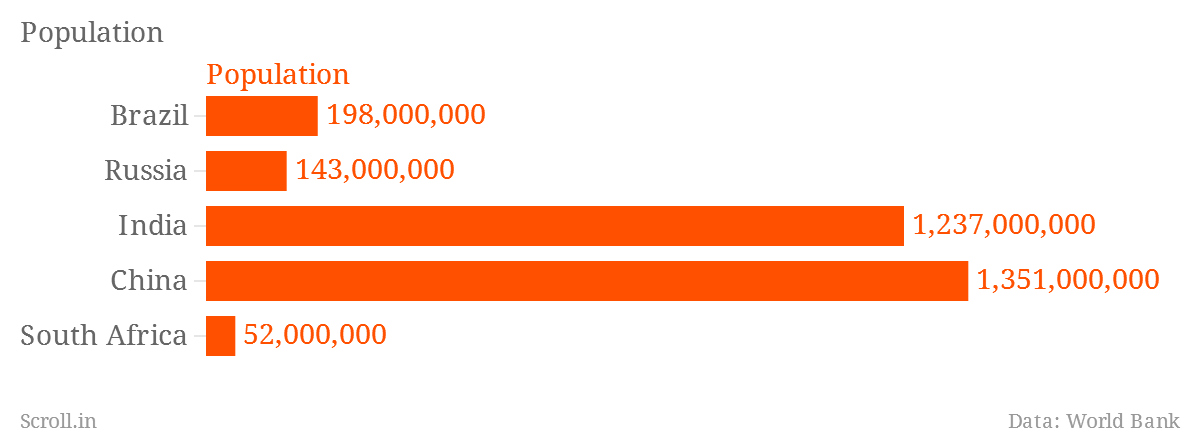

Where population is concerned, India and China are outsized, and will always be in a league of their own. Even so, the disparity here is worth noting. A problem affecting enough people to be considered a national crisis in South Africa would only demand regional interest in China.

Maybe populations are growing at a similar rate? Not exactly. They’re all actually slowing down, from a big picture view, but India and South Africa are still stomping ahead furiously while China has managed to really hit the brakes.

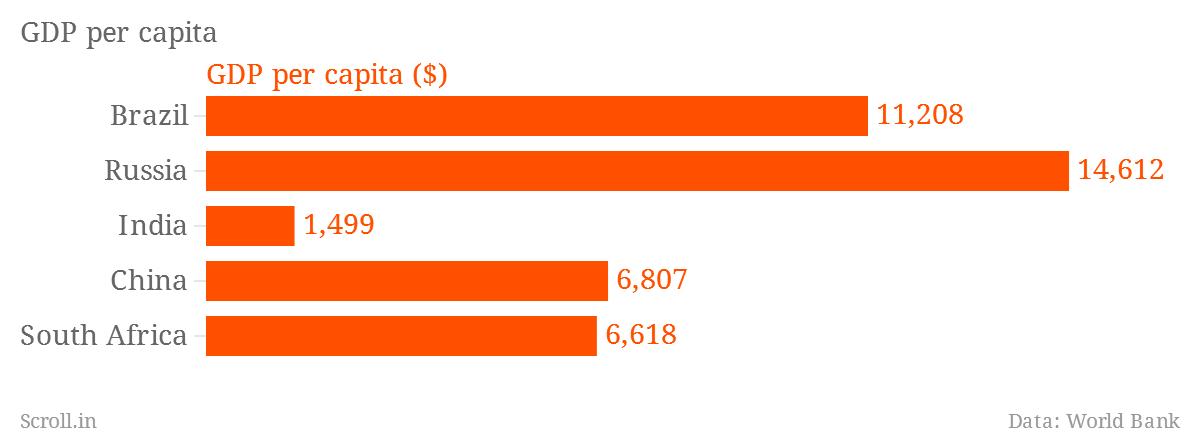

How about income levels? When it comes to per-capita GDP, Russia and Brazil far outstrip the other members of this grouping. India is a serious laggard in this department.

The BRICS countries can’t exactly count on GDP growths rates to be considered equals. Russia and South Africa maintain lethargic sub-2% rates, while China is far ahead at 7.7 per cent. India stands between those extremes.

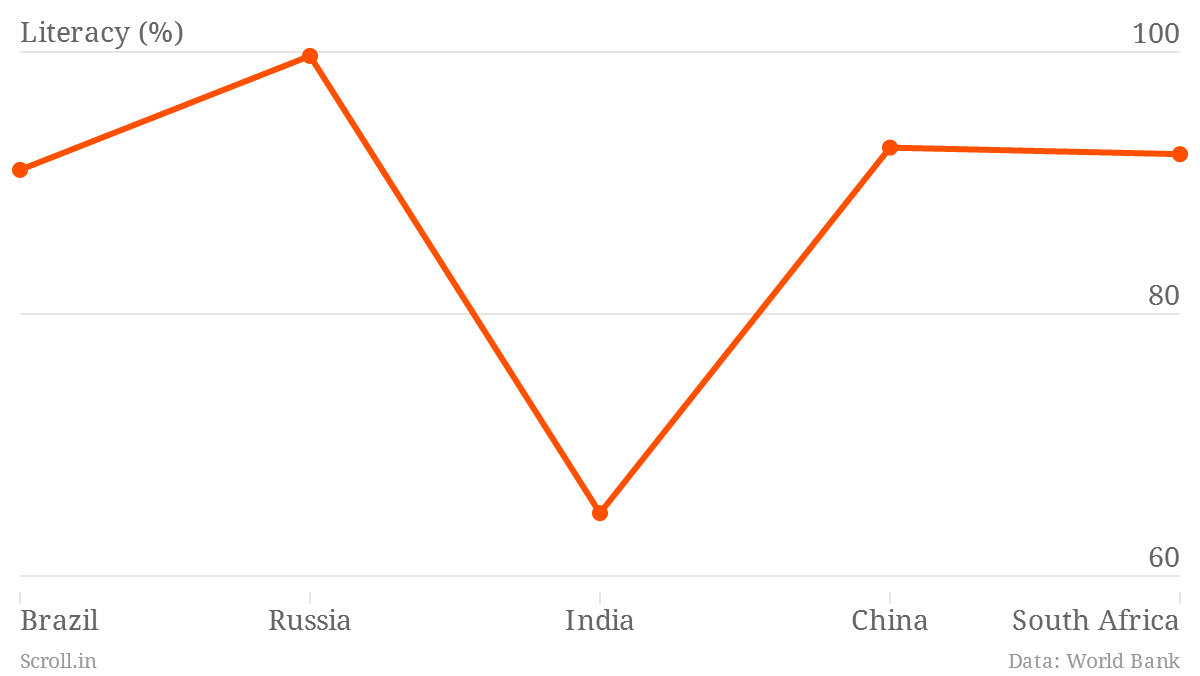

Do social indicators bring them together? All the five countries have tremendous health and education concerns, but they are by no means on the same page. India and South Africa have a much higher mountain to climb in bringing down infant mortality, for example.

There’s actually surprising unity on the literacy front, with all significantly high – at least as per World Bank estimates – except for India, which is struggling at around 65% literacy.

Inequality is also significantly different in each of these countries, as measured by the Gini Coefficient. This measures the disparity in incomes in a country and plots it on an index between 0 and 100, with countries closer to 0 being much more equal compared to those tending towards 100. India here is much less unequal compared with South Africa and Brazil, which have very significant disparities.

This is a Goldman Sachs grouping after all, so global trade and business ought to have something to do with the grouping of the countries. But of course, China is China and simply cannot be compared with any of the other countries on the list, as this chart of net FDI inflows demonstrates.

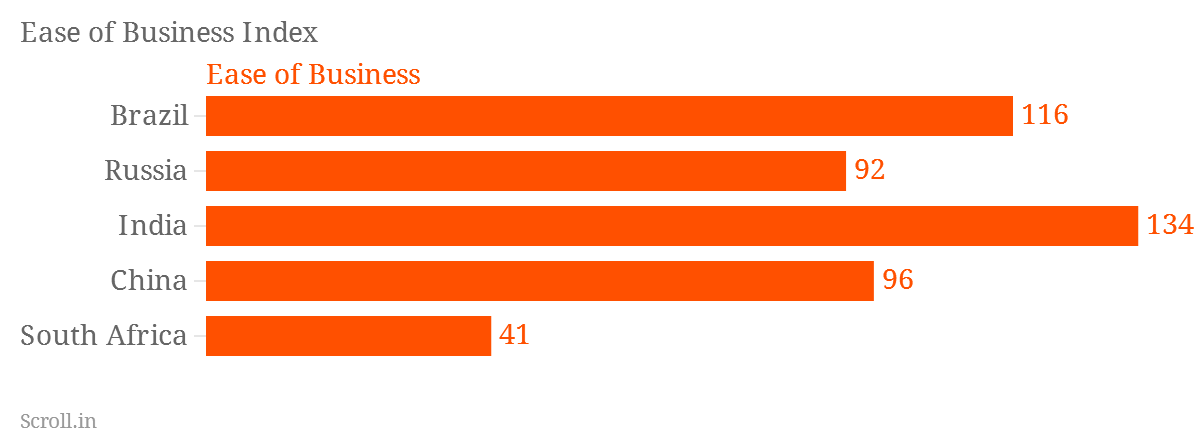

The countries also fall on very different sides of the World Bank’s ease of doing business index, which ranks nations based on the amount of red tape you have to wade through to be working there. The ranking is from low to high, meaning the World Bank considers South Africa significantly easier to do business in compared with India or Brazil.

Maybe it is a united approach towards dealing with global warming that brings these countries together. But the five nations have wildly different amounts of CO2 emissions per capita, with Russia and South Africa far outstripping the amount of greenhouse gases put out by Brazil and India, meaning their motivation and ability to fight climate change also differ substantially.