Rajender Bhatia was sitting in his ground floor apartment in central Delhi on Sunday morning when his neighbour turned up. Kartik, who lived on the second floor of the same building, had come to pick a bone with Bhatia about the parking situation around their building. The argument quickly escalated and, according to the police, a couple of other men also joined the fracas that turned into a proper scuffle.

Then suddenly the 55-year-old Bhatia collapsed, prompting the others to run away and his family to take him to the hospital. The doctors there declared Bhatia dead on arrival and a case was registered against Kartik and the other men, who have since been arrested and booked with culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

Bhatia, unfortunately, is not the first to have died in an argument over parking in Delhi: there have been seven other violent incidents related to it this year alone. And, considering the state of parking in the capital, it’s unlikely Bhatia’s case will be the last.

Police records suggest that 15 people have died in the capital over parking-related issues in the past five years, with many more incidents of violent clashes. Other than the capital’s generally high stress levels, which have given it the reputation of being particularly prone to violence and spats, the huge number of cars being added to the roads combined with limited space is mainly what is behind this unique category of crimes. It isn’t uncommon to see car tires being slashed or a parked car being keyed by angry residents who see it as a way to complain about parking.

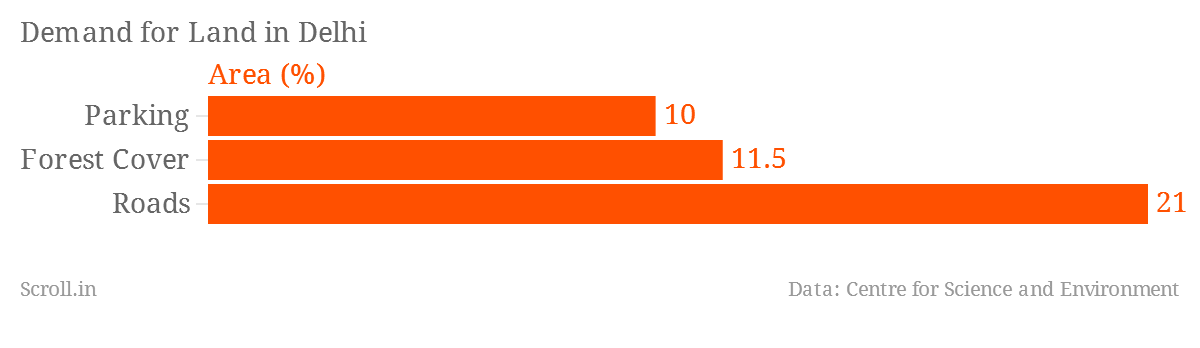

The problem according to urban planning experts, however, isn’t one of inadequate space for parking. A 2009 study carried out by the Centre for Science and Environment concluded that, based on standards laid down by the Delhi government, about 10% of all land in the capital is used by stationary vehicles — just a little less than the forest cover in the city, which is about 11.5% of all land.

Instead, it is a question of incentives and planning. Delhi gives far too much leeway to car drivers even though under 15% of all trips in the capital happen in cars, with the metro, buses and other modes of transport moving much more of the city’s population around.

Yet much of the city has completely free parking — using public land that could otherwise have been given over to other uses — and in the places where you do have to pay to park, the revenues don’t even come close to what the land might otherwise be able to generate.

“Today parking policy in Delhi is only about supplying parking space, all the building bylaws and everything is all about providing space for parking,” said Anumita Roy Chowdhury, executive director at the Centre for Science and Environment. “People have begun to think as if parking is their right that the government should provide for, which is absolutely wrong.”

The city’s transport policy is also terribly weighted in favour of car drivers, as the cancellation of the Bus Rapid Transit corridor showed. The city expects up to 69 sq m to be available to a single car per day, presuming it will park in at least three different places, compared with its standard allotment of just 25 sq m houses for the poor.

“Delhi, in other words, allots more public land per day for parking cars than it does to house its poor. And all this for only 20 per cent of city's population that has a family car, based on figures of the 2008 Household Survey by the Department of Transport,” wrote the Unified Traffic and Transportation Infrastructure (Planning and Engineering) Centre, in a study in 2010.

A study by the Central Road Research Institute also pointed out that the average car stays parked for more than 95% of the time. Yet policy favours cars, provides cheap parking and encourages the buying of vehicles to the extent that car owners have come to expect convenient places to park — something that will be harder and harder for the capital to provide every year to come.

A change in the nature of residential areas is also playing a huge part. As car ownership per person grows, it has become common to see roadsides not meant for parking being occupied by vehicles of all sorts. This ends up obstructing carriageways and entrances, increasing frustration among residents and leading to incidents like Bhatia’s.

“Numerous disputes over parking in residential neighbourhoods with serious law and order consequences have become common in Delhi,” the CSE study into parking policy pointed out. "Parking in residential areas is not managed well, norms are not enforced. Most of the time it is left to the vagaries and negotiating skills of individual car owners. In many residential areas, one is free to park as many vehicles as one wishes on the road and that too at no cost.”

Roy Chowdhury said that it was this conditioning, leading car owners to believe they deserve a parking spot by right, that leads to confrontation and violence when they don’t get it. Because supply is finite, however, she argues that the only way to deal with it is to change the way people think about parking.

“The research clearly shows that parking demand is insatiable. You can never satisfy the insatiable demand for parking. The city doesn’t have enough space to park the cars,” she said. “At one level we should be able to improve the alternative to park, we need to be improving public transport and at the same time you have to manage the usage of cars better. People must pay the right price for using the roads and using public space.”