“You must be getting shocked to hear the Prime Minister speaking of cleanliness and the need to build toilets from the ramparts of the Red Fort,” he said. “But this is my heartfelt conviction. I come from a poor family, I have seen poverty. The poor need respect and it begins with cleanliness…I want to make a beginning today itself and that is – all schools in the country should have toilets, with separate toilets for girls.”

The idea is simple: just like mid-day meals have given children a reason to stay in schools, the lack of latrines should not be the reason girls are staying away.

It has become quite common for the government to look at toilets as a way of empowering women. Whether it is the slogan of pehle shauchalaya, phir devalaya (first toilets, then temples) or narratives of violence like the gangrape in Badaun being the fallout of a lack of in-house latrines, there has been a big shift towards building toilets.

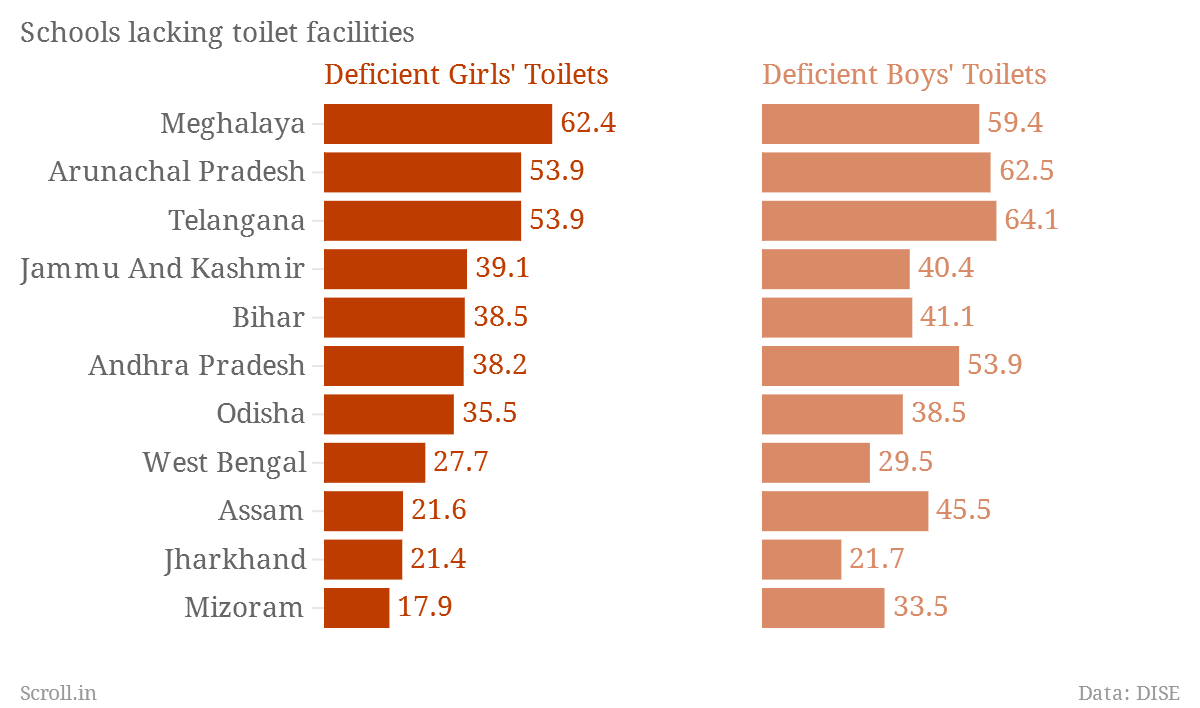

From a big-picture view, the state of toilets in government schools isn’t shocking. Up to 83% of schools have separate toilets for girls that are considered functional by the District Information System for Education survey. Breaking it down by state, the numbers get more problematic.

Surprisingly, matrilineal Meghalaya turns out to be the worst performer, with up to 63% of its schools either lacking girls’ toilets or having ones that aren’t functional. But there is little to suggest that this is a gender-specific issue. Meghalaya does equally badly in terms of the numbers of schools that don't have sufficient toilet facilities for boys, suggesting it might have more to do with infrastructure overall.

This holds true when looking at the numbers of schools with deficient facilities, either lacking toilets or dysfunctional ones, for boys. None of the states with the least number of girls’ toilets do much better with boys’ toilets; there is no great disparity. In fact, most states end up doing worse, having a higher percentage of schools that lack toilets for boys than for girls.

A quick look at the District Information System for Education’s stats on female enrolment seems to suggest there is not necessarily a correlation between states that do badly on the girls’ toilets index and those that have enrolled a lot of girls. Although this might break down very differently if looked at on a district level, the state-wise stats somehow show those areas that have a high ratio of girls-boys enrolment (i.e. the relative proportion of girls enrolled in the school compared to boys) also overlap those areas that don’t have sufficient toilet facilities. Up to 40% of schools in Bihar, for example, don't have proper toilet facilities for girls, yet its girls-boys enrolment ratio, at 0.98, is better than most.

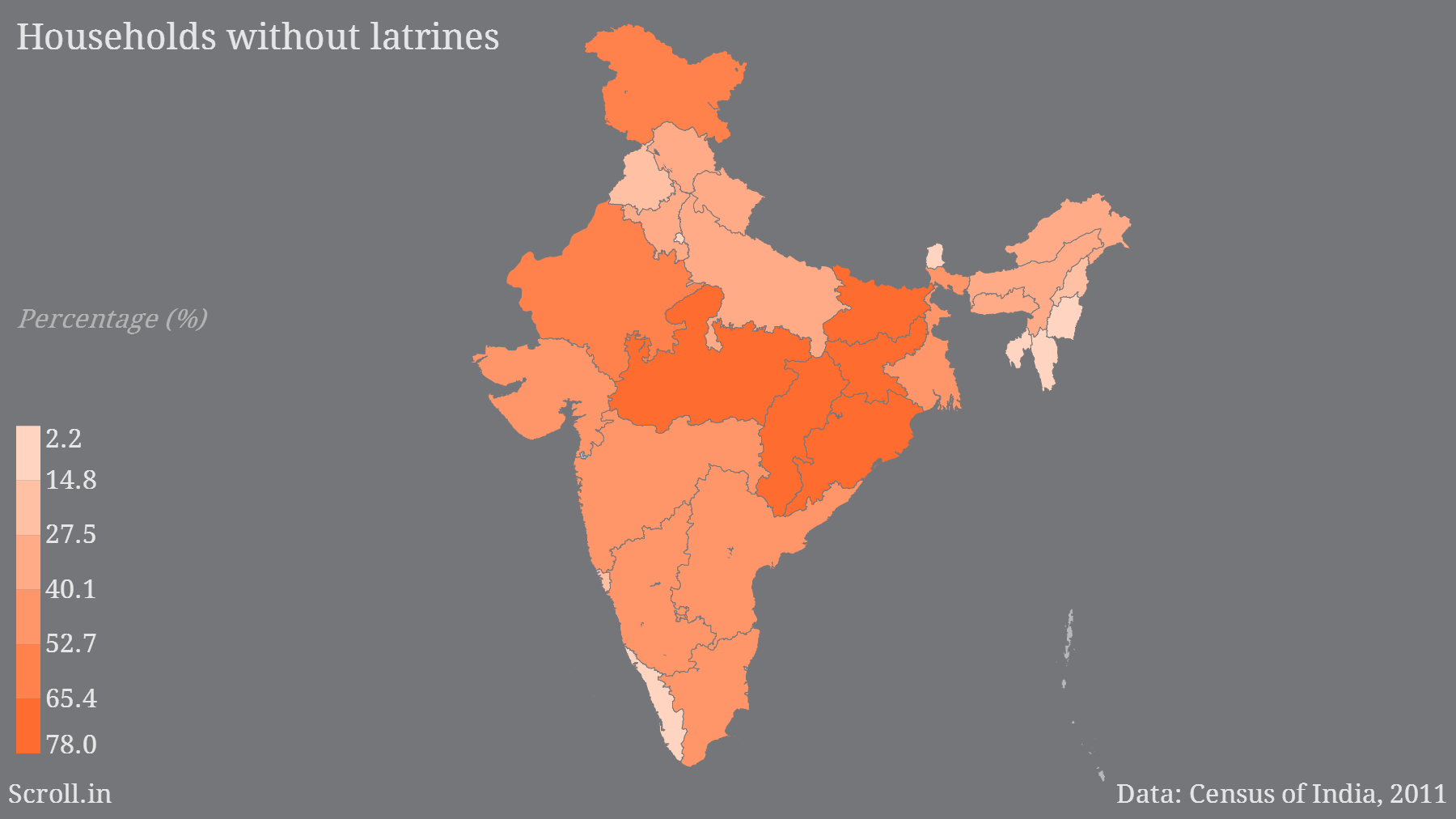

Another way to look at it is to see the census data on households with latrines. Bihar, again, does terribly here: more than 75% of its households do not have a latrine, according to the 2011 census. None of this is to argue the prime minister's call for every school in the country to have separate toilets for boys and girls by the next Independence Day. The lack of toilets also does tend to hurt girls more, but the numbers suggest that it might not fit into an easy narrative about gender discrimination.