Thirty years later, photographer Raghu Rai returns to site of his iconic Bhopal images

Raghu Rai was one of the first photographers to capture the aftermath of the gas leak from Union Carbide’s pesticide plant in Bhopal on December 2, 1984. Three decades later, Amnesty International asked him to go back.

This victim was identified as Leela, who lived in the Chola colony near the Union Carbide factory.

I was in bed at home in Delhi when my editor at India Today magazine called me in the middle of the night. His call was swiftly followed by one from Magnum’s (photo agency) Paris office. Everybody was buzzing with the news – at midnight there had been an enormous gas leak at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal and thousands had been killed. I didn’t sleep, jumping on the next morning flight and was in Bhopal by 8 am.

From the plane, a huge crowd of press descended on the city. We ran towards the hospitals, looking for dead bodies. Afterwards I would feel guilty about that, but in the moment there was no time to think, just shoot. From the moment I touched down to the moment the sun set.

Mass cremation of victims held alongside the communal graves.

Bhopal, 2002. View of the town.

When we got to Hamidia hospital the chaos was overwhelming. I had never seen anything like it, it was as if a war had just ended or in the aftermath of an earthquake. The sick were being brought in and the dead brought out, people were running everywhere. I went about taking pictures – capturing everything and anything that came my way: bloated bodies and dead animals lying on the road. There was a strange kind of silence – the silence of death.

As a journalist, you avoid getting emotionally or sentimentally involved, but I experienced a strong suffocating feeling the whole time. The fallout was so huge, so unbelievable. I focused on capturing the tragedy and its emotional fall out – women crying as they tried to find their children. Parents watching their children fading into death.

I didn’t eat, didn’t stop until the light faded – it was now or never and no one knew what was waiting the next day. I stayed another three days before I left. It was an endless affair, but how many sick people and dead bodies can you photograph?

No matter how many shots I took one couldn’t capture the scale of it.

One always feels inadequate seizing only fractured moments, losing what is happening just to the left or right of your frame and the experiences you go through in those moments. When I looked at my pictures at the end of the day it had taken such an enormous pile of expression and intensity, but still you feel – oh my god, it was so enormous and I have only been able to get this much of it.

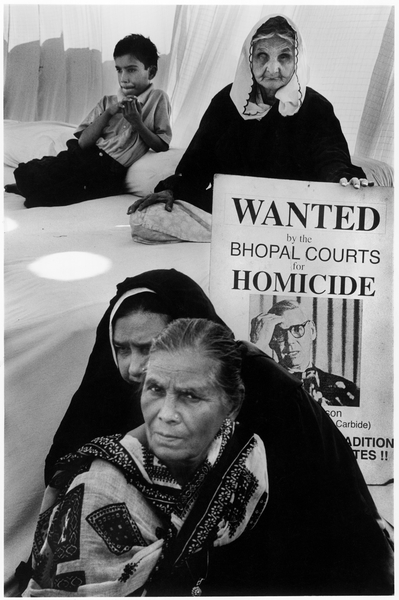

Bhopal survivors protest in New Delhi, to demand the extradition of Warren Anderson, former chief executive of Union Carbide. Anderson died last in September.

Survivors of the 1984 Bhopal gas leak protest outside the Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister’s residence, demanding proper compensation, September 2014. Abandoned to poor health care and paltry pay-outs, survivors have fought for three decades for the corporations behind the disaster to be brought to justice in one of the longest people's struggles in India.

Survivors of the 1984 Bhopal gas leak chain themselves in protest to the fence outside the Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister’s residence, demanding proper compensation, September 2014. Others stage a die-in, draped in sheets bearing the chilling image of a dead child – a photograph that has since become synonymous with the tragedy. Abandoned to poor health care and paltry pay-outs, survivors have fought for three decades for the corporations behind the disaster to be brought to justice in one of the longest people's struggles in India.

I went back after a few months, again after one year, and then here and there another 12 to 14 times. It was later that I was able to dig deeper and find out more about the disaster and the suffering.

Every trip there was another story. I remember being shocked that research had been done on this gas, but no cure and no antidote had been revealed because Union Carbide kept it secret.

Patients at Sambhavna Clinic, which runs free clinics for survivors of the gas leak. The clinic, set up by activists, provides vital care where government efforts have failed.

India is a country where anything is possible and a country that can be so chaotic that nothing is possible. For the following years there was a feeling that nobody gives a damn. I didn’t get the feeling that the people who were still suffering were being looked after or cared for, you couldn’t see a collective effort to improve the lives of these people.

It was frustrating to keep covering – like knocking your head against a wall, like nobody cares, even the ministers. They used to ask me, "Why do you dig up these skeletons, these people are dead and gone?" They didn’t understand that those people who inhaled less gas and survived, they were the worst off, dying a slow death. They were not ready to believe it, the politicians. And they didn’t care about these wretched of the earth.

Yet people somehow managed to live their lives despite all the chaos and the problems. They have accepted it, but you can make out the withered fatigue on their faces. These will never be people able to lead a happy life.

Now the factory is rotting and rusting, but all around it is fresh greenery, just amazingly green and colorful – children are playing there and people are grazing their animals. Then you see a fine layer of powder and it looked so fresh, I reached to touch it. The guard stopped me. It shocked me that 30 years later, potentially dangerous materials remain untouched. You would hope that there is some possibility of government intervention. But India is a country where everything is possible, and India is a country where nothing is possible.

A patient at Sambhavna Clinic, which runs free clinics for survivors of the gas leak. The clinic, set up by activists, provides vital care where government efforts have failed.

All images courtesy Amnesty International © Raghu Rai / Magnum Photos.