But how real is this spectre of ethnic discrimination in the nation’s capital, believed to be the number one destination for North Easterners looking for jobs? The Reachout Foundation, an organisation dedicated to ending discrimination decided to try and find out.

“With frequent reports of alleged racist attacks in Delhi and the National Capital Region, Reachout Foundation perceived a lack of comprehensive data on the nature of alleged discrimination against people from Northeastern India in cities like Delhi," writes Kishalaya Bhattacharjee, director of the foundation in a new report that reveals the results of a survey. "Our emphasis thus has been to generate comprehensive and defensible empirical data on the extent and variation of racist attitudes and experiences, in order that they could inspire or guide anti-discrimination policies."

Workers from the foundation spoke to 1,000 people from the eight North Eastern states living across the National Capital Region, in order to gain an understanding of what it is like to be discriminated against. “Whether society can be shaken out of its apathy remains to be seen, but it cannot be allowed to inflict so much suffering in a smug trance. The first step must be to hold a mirror up to society, and to persuade it to look into it,” Bhattacharjee wrote.

First come the basic questions. Are you discriminated against, and how often does it happen? Nearly half of those surveyed said that they feel discriminated against because of their ethnicity sometimes, with 24% saying they had never faced such prejudice and 10% saying it happened often.

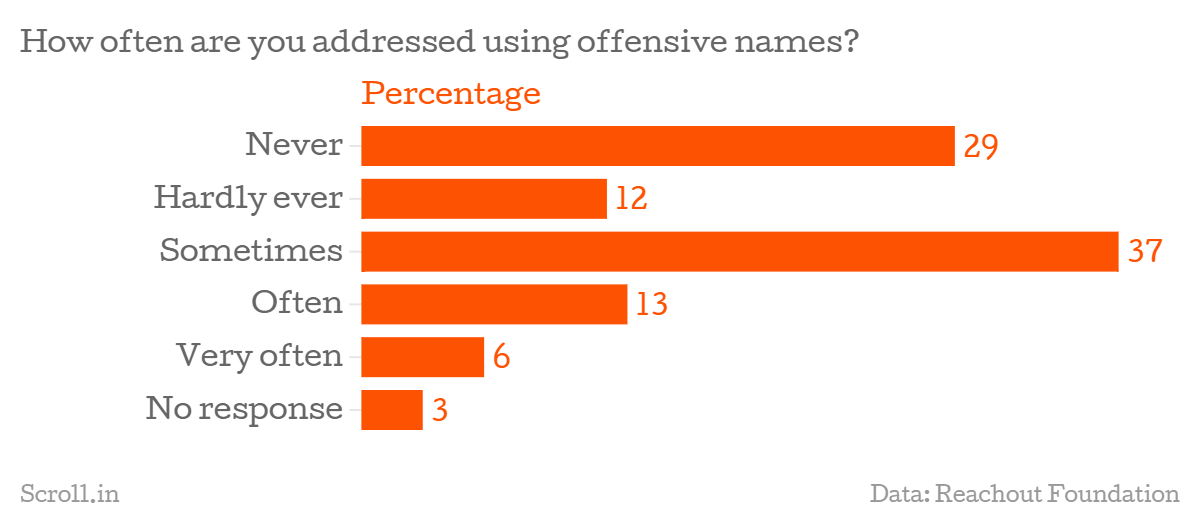

Considering one of the most common ways to demonstrate prejudice is through pejoratives, the survey respondents were also asked how often people using offensive names to call them. Here again, nearly half said it happened either sometimes or often.

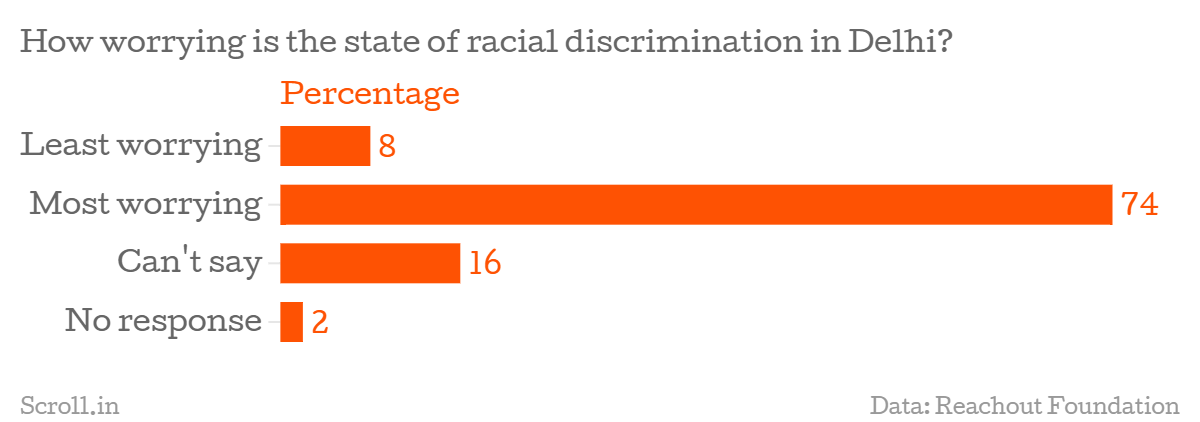

And even for those who did not feel discriminated against personally, prejudice was a problem. The survey included a question on how worrying the state of racial discrimination in Delhi is, and three-quarters of respondents said it is “most worrying”, with only 8% saying it is “least worrying.”

Although this might have been skewed because of the spread of population of North Easterners in the national capital region, who tend towards the young, either students or professionals, the survey also showed that the perception of discrimination was drastically higher for those in their 20s as opposed to either the younger or the older.

That said, it’s not all bad news. When asked whether they believed it is possible for Delhi to be rid of discrimination, or at least if the problem can be addressed, almost half of the respondents said it could be done. A third, however, said it was not possible, while the rest were ambivalent.

As to how the city must go about it, the respondents were clear that the best way to address racial discrimination was through education. This applies on both ends. Education, in their minds, would not only reduce the likelihood of being prejudicially treated the survey also found that North Easterners with education were more likely to report problems if they have been discriminated against, and therefore do something about the issue.

The onus, in the minds of the survey respondents, is squarely on the government and the police to take charge of the problems. But after them, 30% of those surveyed said social workers need to be doing more to address discrimination with another 17% saying it should be the ethnic groups themselves that should work to address these issues.

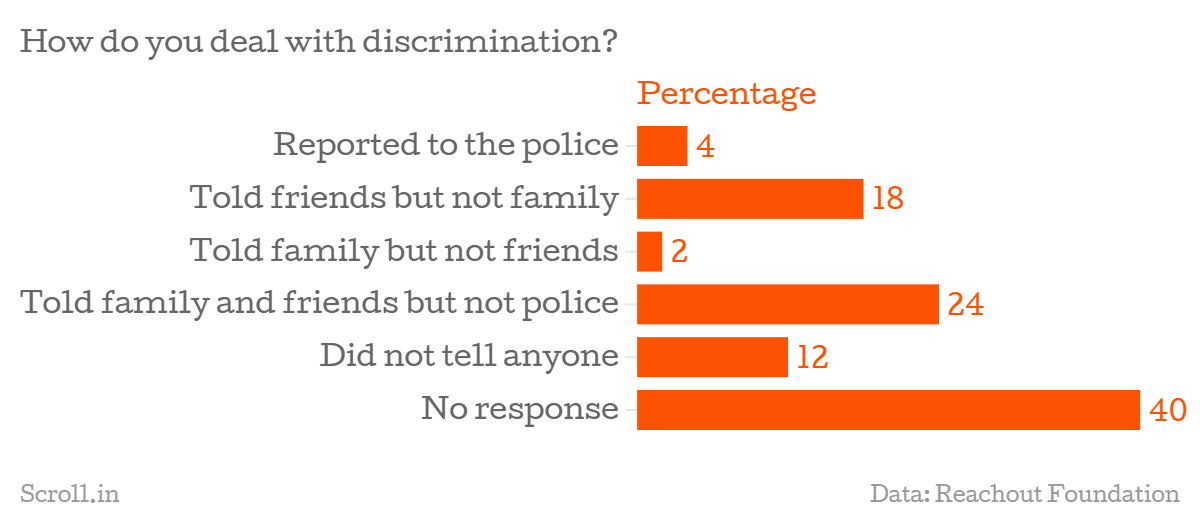

Despite this expectation that the issues have to be sorted out by authorities, though, only 4% of those who had faced discrimination said they reported this to the police, with many more saying they were more likely to tell friends and family about such incidents instead of law enforcement.