This week, India’s largest collection of Baluchar silks will be on display at an exhibition in Mumbai's Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya titled Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silks of Bengal: 1750-1900.

Curated and researched by Eva-Maria Rakob, Shilpa Shah and Tulsi Vatsal, the exhibition will showcase what is perhaps the most definitive research on how the short-lived textile industry thrived and fell over the course of a century.

Several silks woven today derive patterns and weaves from Baluchar silks, but real Baluchar saris, say Shah and Vatsal, come only from Baluchar, a town near Murshidabad in West Bengal that no longer exists.

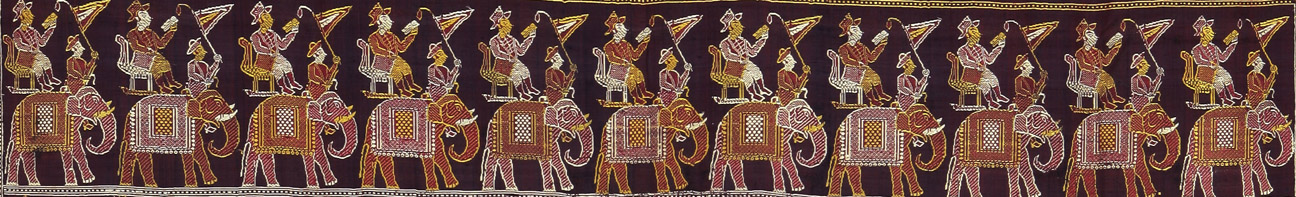

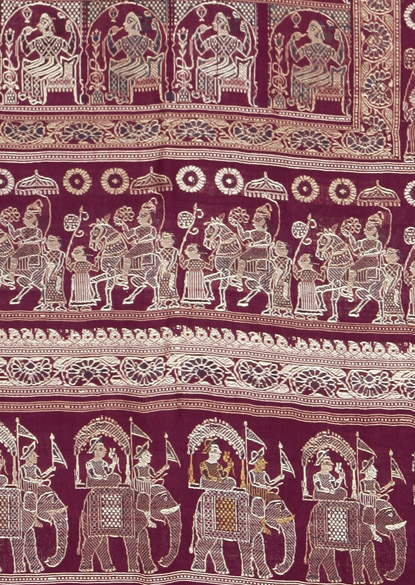

Baluchar silks were lavish textiles made for the wealthy between the 18th and 19th centuries. Unusually, they used no zari, relying instead on rich and intricate weaves that echoed the social and political preoccupations of their time. Common on them were images of steamers, women on horseback, Europeans on elephants, even cannoneers.

Baluchar sari with Nawab and sahibs in train; mid-19th century. Photo credit: Tapi Collection.

Baluchar motif with hookah-smoking Nawab and canonneers; mid-19th century. Photo credit: Tapi Collection.

Baluchar’s weaving industry was probably already present when the Mughal governor of Bengal moved the region’s capital from Dhaka to Murshidabad in 1704. The industry had begun to decline by the time the British moved their capital from Calcutta to Delhi in 1911. Between 1900 and 1903, Dubraj Das, “the last weaver who knew how to assemble and operate the complex Baluchar drawloom”, died – and with him, the old Baluchar weaving tradition.

Short-lived but popular

Shah has been gathering textiles for her Tapi Collection since the mid-1970s. By the end of the 1990s, she realised the collection had an important group of textiles that had stories that needed to be told. She organised a few exhibitions in India and abroad, but her first collaboration with Vatsal – on a history of Parsi embroidery – was published only in 2010. The Baluchar project, which they began working actively on only three years ago, is their latest together.

“We felt that the Baluchar silks of Bengal had not received the attention it deserved, though they reflected the times in which they were made” said Shah. They travelled well. Shah says she did not buy the majority of the 68 Baluchars she and her husband possess in Bengal, but in places such as Delhi, Agra and even Hyderabad.

Unlike other classical saris that relied on mythological art, Baluchar’s silks stood out for their strikingly secular patterns.

Sari with Nawab smoking hookah and European riding elephant; mid-19th century. Photo credit: Tapi Collection.

Their styles seem to draw from contemporary visual art, but Vatsal and Shah say there is no way of being certain which way the influence went. “There is so much we do not know,” said Shah. “We found it surprising that weavers would put male figures on saris meant for Indian women. But the art seems to have come from a common pool.”

Vatsal added, “Perhaps people thought it was fashionable.”

“Or perhaps these were to depict the people in power,” Shah continued. “That would explain why there are more male than female figures. But there you are. We don’t know who the patrons or clients could have been.”

There was obviously a luxury market for this kind of silk, Shah said, but by the end of the 19th century, it was replaced by Banarasi saris. The zari work on those saris was far more grand and cheaper than Baluchars.

Plugging the gaps

Uncertainty seems to be a defining feature of Baluchar’s silks. History is unusually silent on the subject. The primary source that forms the basis of much scholarship is an 1894 monograph by NG Mookerji, a collector in Murshidabad who was asked to report on and revive the textile arts of Bengal. Most subsequent work is based on speculation.

“There are many coffee table books and magazine articles without any real study of the materials, which had myths proffered and propagated,” said Vatsal. “But only two contemporary records actually mention Baluchars.”

Masterpiece with three figural motifs: Raja on horse, woman smoking hookah and sahib on elephant; mid-19th century. Photo credit: Tapi Collection.

The only real study of the silks they found was done in 1993 by Eva-Maria Rakob, a German scholar who came to India to study textiles for her Phd thesis. Her thesis was never published, except for an excerpt in the Art India magazine. Rakob had studied 370 pieces of Baluchar fabrics around the world for her thesis, including those then in the Tapi Collection. When Vatsal and Shah contacted her 20 years later, she agreed to update that research.

There were several gaps and unanswered questions in this text, which Shah and Vatsal attempted to fill with their own studies based on Shah’s collection.

‘It came and went like a meteor’

Given Baluchar’s responsiveness to its time, it might seem unusual that the style died so abruptly with the death of the last weaver.

“It came and went like a meteor, almost exactly coinciding with the nawabs coming from Murshidabad and the British moving to Delhi,” said Vatsal.

A bibi or courtesan smoking hookah; mid-19th century. Photo credit: Tapi Collection.

Other styles, Shah pointed out, were more adaptive. Banarasi weavers, for instance, were able to mimic other regional styles and were more alert to change. Today, they cater to designers from the west and to domestic markets, while still retaining their character. Banarasi saris might today come in cheaper silks and cotton or have synthetic zaris, but Shah and Vatsal have not yet found a single Baluchar in cotton.

“Baluchar was unable to adapt to the times,” Shah explained. “The designs were not classical, traditional or time-honoured. They were what you might today call trends that came from the imagination of the artists. Since consumers took to them when they were new, they therefore also had an expiry date.”

Exhibits from Sahib, Bibi, Nawab: Baluchar Silks of Bengal: 1750-1900 will be on display at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalay, Mumbai, from December 12 to January 11.