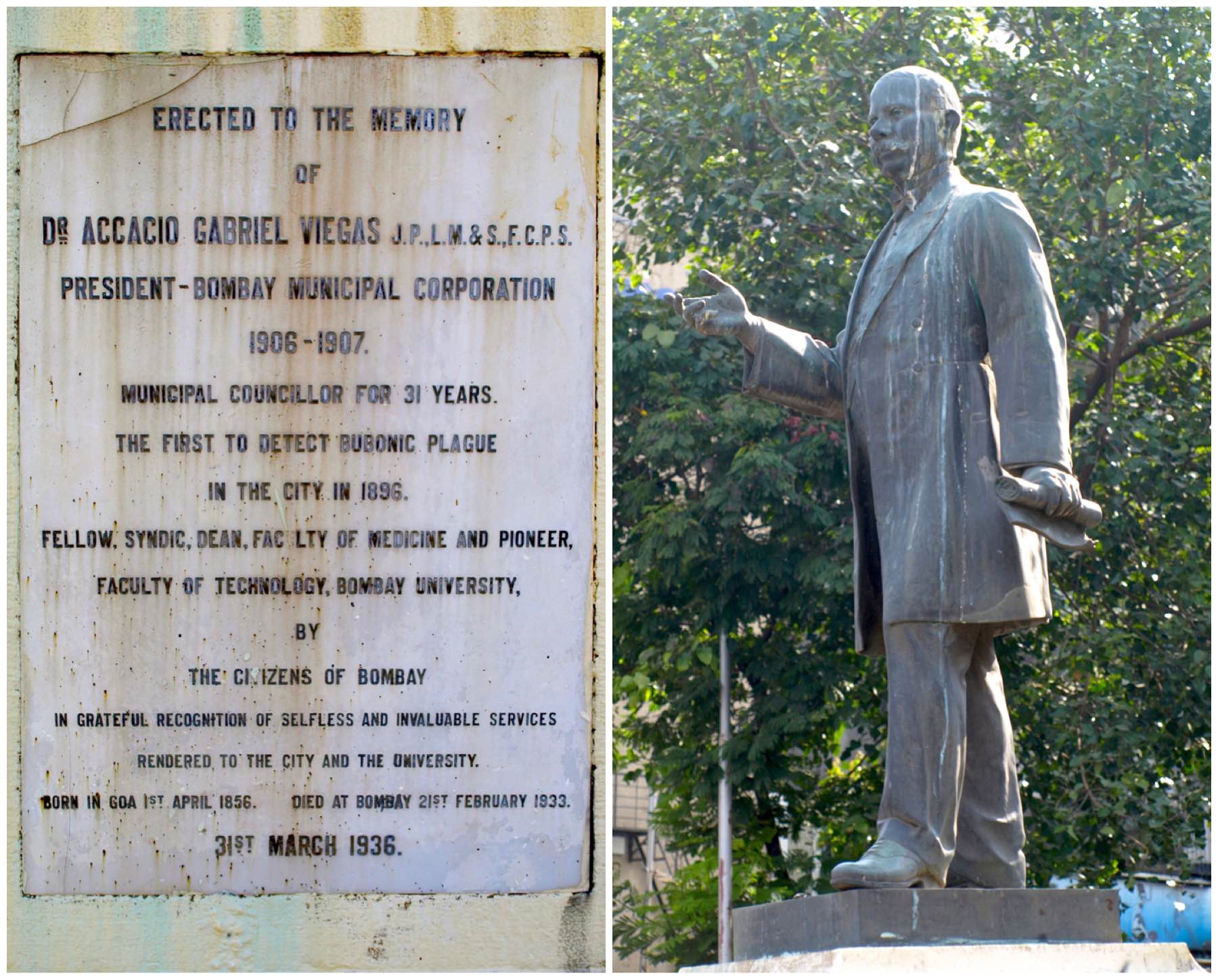

The statue has Dr Viegas in his sixties, a wiry man in a doctor’s coat. His face is difficult to define. He’s wearing the standard disguise of the Victorian professional man: a pince-nez and a bottlebrush moustache. The sculptor has captured a nervous edginess that, to me, explains the man. Restrained by a railing, he seems to shake a fist at the city that wheels heedlessly by.

His venerable head is a little encrusted with bird droppings. On most days the plaque that tells his story is concealed by a hawker’s flashy display. But I suspect he wouldn’t mind a bit. That plaque would have embarrassed him. He would have found the hawker’s history more interesting. He was a man of the masses, they tell me. But that was long after he became a legend.

The Accacio Viegas I know was not quite as mellow. The year I met him the city had plunged headlong into chaos and he was at the helm of it.

That year, Accacio Viegas had just turned forty. His practice in Mandvi was booming, and he had been recently elected to the Municipal Council.

Accacio, after hours, was a very different man from the grave physician his patients knew. He was a dreamy-eyed romantic, inclined to music, a classicist who read Camões—but not Bocage. He was a sharp dresser with a luxuriant crop of curls he tried in vain to tamp with pomade.

On weekends, with social obligations to be met, he changed identity. Nothing was quite as embarrassing as being accosted by last week’s consumption or yesterday’s cirrhosis on one’s way to a tea party. This wasn’t Goa, where the hierarchy was absolute. There were no such niceties in Bombay, these Indians were a junglee lot. But he had his own ways of escape.

He had learnt the trick from Mr Arbuthnot, a dry wit who was supposed to lecture undergraduates on Botany. Instead, Mr Arbuthnot read aloud to the class essays that explored the quirks of human nature.

From him Accacio heard the story of the Sunday Gentleman. Daniel Defoe, bankrupt and likely to be arrested, would lie low all week. British law did not allow debt collection or arrest on Sundays, so on the Lord’s day, Defoe would strut about London confident of immunity. He died on 24 April 1731, still dodging his creditors.

As his practice thrived, Viegas, though far from bankrupt, found himself copying Defoe. He strolled out on Sundays confident none of his patients would recognize him.

The dark suit with its frock coat was put away with his weekday gravitas. Out came the racy Sack jacket to allow a swing in his step, and one of the new waistcoats that dared a glint of colour. With his spotless white gloves and ivory-topped cane, as he stepped into his phæton on his way to Church, not one of his patients would recognize him. For that brief day, safe from human tribulations, he could be quite the Sunday Gentleman.

Nothing set 18 September 1896 apart from other Saturdays.

Like any other morning, it was hot and crowded, but Dr Viegas was used to both heat and crowds. He abandoned his carriage at Pydhonie and picked his way through the labyrinth that led to Vor Gaddi. An unfamiliar name, an unfamiliar locality. Its civilized cognomen, Samuel Street, held no ægis over these twisting by-lanes.

He hurried, to keep his guide in sight. Luckily the man wore a red turban, and Viegas ducked and dodged coolies and carts, almost doubled in his haste to keep that flash of red in view. He would never find his way out of this place on his own.

The man in the red turban had been waiting at the gate when Dr Viegas reached his clinic at nine. He looked as if he had been waiting a long while. He was crouched on his haunches, compacted against the wall.

Viegas knew it was a serious case at first glance. He was long used to the native stance of despair. The man rose hastily, and greeted him with folded hands. That meant a house call, with no hope of a fee.

Viegas was used to that too.

He unlocked the clinic. Darab, the compounder, was late, as usual. Drunk, probably. No matter, a whistle would fetch a boy from the bakery to keep shop till Darab showed up.

The man in the red turban was badly frightened. He seemed ready to break into a run and expected Dr Viegas to run with him.

It was no use asking him what was wrong.

‘She’s very ill,’ he kept repeating. ‘You must come right away.’

‘Where?’

‘Vor Gaddi.’

‘Where’s that?’

‘Pydhonie.’

It was barely two miles away. But that was as the crow flies, and this city wasn’t planned from a crow’s perspective.

‘I’ll take you there,’ he urged as Viegas hesitated.

He ran alongside the carriage the whole way.

When they got to Pydhonie, he shuffled impatiently as Viegas left his carriage at the chowki. When they started off again, despite having run for nearly an hour, he quickly outstripped the doctor’s brisk stride. These natives! One wondered where they got these sudden bursts of energy. Dr Viegas, surprising the thought, smiled at himself. He felt almost European on weekends.

Vor Gaddi was a maze of tenements built across a reticulum of open drains. The buildings faced each other across narrow galis that were little more than strips of brick. The tenements, most of them four or five storeys high, looked crazily askew. Huddled within a patchwork of balconies, each one was bright with washing. It looked as if a giant clothesline had bundled together all of humanity.

If only it were that simple. He had lost count long ago of the different types of native. Easier far to see them all as one distinct race. Or two. The rich and the poor. The rich were slowly growing civilized, but there was little hope for the poor.

The poor were everywhere in Vor Gaddi, the place exploded with them, a tangle of black limbs, white linen, and the occasional coloured turban, like his guide’s. It was not a turban at all, just the usual red towel natives favour, wound clumsily round the head.

The house of sickness was easily identified. An expectant knot of people crowded the narrow doorway, cutting off any stray breath of breeze from the narrow gali.

They parted respectfully as Viegas approached. Somebody relieved him of his bag. He handed his hat to another.

The dim interior did not take him by surprise, He had been in dozens of houses like this before. Like all natives of this class, the sick woman was bedded on the floor. She lay on a thin pallet, huddled within a confused heap of clothes. Every piece of clothing in the house seemed piled over her.

Swiftly, he organized space, light, co-operation.

The men left the doorway.

Only Viegas’ guide stayed, his face averted, his young shoulders tense, alert to the doctor’s command.

The sick woman was his mother, Viegas concluded. That alone could explain his panic.

These natives treated their wives with scorn. The delicate attentions of romance were alien to them, but the bond between mother and son was always passionate.

A young woman spread a sari across a clothesline, excluding the rest of the room.

Within that small space now, the light from the high window cast fewer shadows, and he took his seat on the low stool placed for him at the bedside.

‘What’s troubling you, ben?’ He didn’t expect her to understand his brand of Gujerati, but he tried. ‘What’s her name?’

‘Mother,’ replied the daughter.

‘How are you feeling now, Ba?’ he amended.

The young woman repeated his question in her dialect, and the patient responded by muttering a few words and pushing her hand away.

‘She says let me sleep.’

‘How long has she been sleeping?’

‘She hasn’t woken up at all today. I tried to give her some hot milk, but she wouldn’t drink it.’

Viegas felt the patient’s skin. The fever was moderate, about 102ºF, not enough to explain the drowsiness.

He tried rousing her again.

She stared at him briefly with bloodshot eyes and protested with an indignant sound, but her voice trailed away as she relapsed into stupor.

He lifted her head gently, smoothing away the hair from her damp forehead. Her slender neck was supple in his hand and offered no resistance. Not meningitis, then.

What could explain her drowsiness?

This was no ordinary fever. The bounding pulse meant a beleaguered heart. Toxæmia. Frowning, he went about the examination, concentrating every sense till the stuffy room, the street noises, the heat and cooking smells all disappeared and the only thing he was conscious of was this helpless body at war with itself.

One by one, Viegas travelled the body’s landmarks. The breath sounds were gentle and murmurous, the chest moved symmetrically, the lungs were fine. There was the systolic murmur expected of an overtaxed heart, but no specific cardiac illness. The liver was not enlarged, and neither was the spleen. The abdomen was soft, nothing there. No neck nodes, no skin eruptions.

‘Please look at this.’ The girl slid down the waist of her mother’s sari.

Viegas found himself staring at a swelling as big as a marble beneath the papyraceous skin of the groin. It was not inflamed, but he didn’t need to touch it to know it was exquisitely painful. The patient’s face was puckered already in agony.

‘It was smaller yesterday, and not so painful,’ the girl said.

A lymph node, just below the sag of the ligament, a femoral lymph node.

Lymph nodes were dustbins for the body’s periphery, stationed locally to siphon off infections before they could spread.

This node was enlarged because it drained toxins from a neighbouring area. And the genitals were well within its provenance, so Viegas’ first instinct was to suspect venereal disease.

A covert examination, a peep down the raised waistband was hardly conclusive.

Viegas’ suspicions were all with the husband he had noticed outside, a greying ruffian, a most likely source of venereal disease. He would question him later. Meanwhile there was nothing else really—no wound or infection on the legs—to explain that stray lymph node. And nothing except that lymph node to explain the fever and toxemia. Completely inexplicable.

Completely inexplicable, unless—

No, that was impossible!

Dr Viegas brushed the thought angrily away and picked up his bag. He asked the son to accompany him back to the clinic, at an easier pace, this time.

Darab was in, and the waiting room was packed. He got Darab to make up a diaphoretic powder and an infusion of quinine.

‘Let me know this evening if she’s any better,’ Viegas told the boy and turned away impatiently when the boy lingered for reassurance.

The day seized him. He had to clear the waiting room in time for the genteel practice that started at four.

There was no time for lunch, but he got Darab to fetch him a couple of bananas and a glass of milk to stave off heartburn. Anxiety had his stomach in a gripe by now—and what on earth was he anxious about?

Hastily, he blocked off the thought.

The last patient was on her way out now, with the clock edging towards half past three.

He looked at the bananas with distaste. He gulped down the milk, refreshed his face and neck with a damp towel, and considered a nap.

Eyes closed he let his brain play the second movement of the Chopin concerto he loved, but today instead of the oneiric drift of notes all he heard was the plutonic whump of a pulse, doomed, and close to terminus.

He was almost relieved when the bell rang.

The carriage at the gate was an ornate one. A rekla, but richly caparisoned, and with a cushioned interior that converted a ramshackle cart into a fairly decent conveyance. A rich Marwari, he decided, and pushing the remains of his hasty meal out of sight, patted his hair down with the towel and awaited his patient.

The rich Marwari was in perfect health, but his nephew, a boy of sixteen was not. The few steps from the gate into the waiting room had got the boy dizzy and he was stretched out on the bench.

‘Perhaps I could tell you the story of his complaints,’ the Marwari began, settling himself in Viegas’ office. ‘By the time I finish, he’ll feel strong enough to walk in here.’

The story, it developed, was merely high fever.

‘He’s my brother’s son. You understand, the responsibility weighs heavily on me,’ the worried uncle said. ‘Use the most modern medicine, Doctor. I cannot betray my brother’s trust.’

Assuring him it would take more than a simple fever to accomplish that, Viegas stepped out to examine the patient.

Why had he expected him to be stuporous? The boy was wide awake. He looked angry as he tried to rise and fell back, exhausted. His thin banian was soaked with perspiration. Good! He should be better by sundown.

The fever was very high—104º. The eyes were bloodshot, but as Viegas placed his hand on the boy’s chest, the stare of distress was slowly replaced by calm. Viegas talked to the boy gently as he examined him. He relied more on words of concern and encouragement than useless nostrums, but had learnt early that patients were quick to spot empty assurances and false cheer. Quite without intent he found himself examining the boy’s groin well in advance of anything else. He even surprised himself using the antiquated term in his case notes.

Bubo absent, he wrote. What had got into him to do that?

He prescribed the usual quickly and saw the patient off with hearty encouragement. To the uncle, he advised patience. Twenty-four hours, at least, must pass for the fever to disappear.

‘Let me know if he develops a swelling’—the words were out before Viegas could stop himself.

‘There?’ The uncle indicated the groin.

‘Neck, armpit, groin—anywhere.’

The first patient of the afternoon was here already, a bearded Mussalman grandee with his purdah-nashin wife. Viegas remembered that Ahmad Momin had requested this early appointment for his wife. It would not do to upset the lady by confronting her with two strange men in the room.

Viegas led the Marwari and his nephew out through the side door and lingered as the boy was made comfortable in the rekla. He stood there loth to go in till the cart vanished from sight.

It was past seven when he shut shop.

The lamplighter had come and gone.

Viegas was late. He was second violin in the orchestra, in rehearsals for Christmas at Gloria Church. The opening notes of Vivaldi’s Primavera were already unfolding in his brain as he hurried towards his phæton.

‘Doctor Sahib!’

It was the young man from Vor Gaddi.

Viegas took a moment to place him because he was without his red turban. His mother was better. The fever was going down. She had accepted a few spoons of kanji and was now sleeping peacefully.

Viegas almost sang out in relief. How absurd his foolish terrors seemed now. He clapped the young man on the shoulder and sent him on his way.

Music failed to soothe him that evening. Sleep eluded him.

First light flickered over the coconut trees when he was woken up by the dog. Captain was barking—a tentative, questioning, bark. There was someone at the gate.

Viegas slid out of bed and padded barefoot like a native, careful not to wake the sleeping house. Sundays were slow and lazy in the Viegas family.

It was still misty, but even from a distance he recognized the figure at the gate.

It was the young man from Vor Gaddi. His mother had worsened during the night. He had been wandering for more than an hour trying to locate Dr Viegas. Finally a gharrywallah had directed him to the house. Now they must hurry—

How? Viegas looked hopelessly at the mist-shrouded street. His horse was stabled near his clinic. His carriage would arrive only after lunch, cleaned and gleaming for the children’s Sunday outing. Not a gharry in sight at this hour—which left only one alternative.

Assuring the anxious man he would be with him soon, Viegas dived back into the house. He dressed noiselessly and crept across the back garden to the shed, praying the creaky door wouldn’t wake his wife.

There it was. It gleamed in the half-light like a beloved’s glance. His new bicycle—a silver Raleigh Safety. Secondhand, yes, but he suppressed that hastily. To him the bicycle was still virginal, untried. His wife had declared she would kill herself before she let him venture out on ‘that contraption.’ He pointed out ‘that contraption’ was all the rage on the Esplanade on Sunday afternoons. That drove her to an even higher pitch of protest. Paloma was less of a lady on weekends. Sometimes she even spoke like a native.

Of course he had kept from Paloma the real facts in the case. The previous owner had taken a toss. Scalp laceration, twelve stitches. No underlying fracture of the skull—thanks to the pneumatic tyre. What an invention—one was quite literally riding on air!

Through the sleeping streets Dr Viegas sailed along like Montgolfier, with his guide panting after him. At Pydhonie he alighted without too much loss of dignity and parked the bicycle at the chowki. They knew him there.

They were still an intersection away from Samuel Street when Viegas’ guide abruptly abandoned him. He darted forward in anguished haste, leaving the doctor far behind.

Not for the first time Viegas marveled at native intelligence. It seemed triggered by a completely alien set of stimuli. What had warned this man there was already a crowd at his doorstep?

As Viegas neared Vor Gaddi, he noticed the street was awake but frozen in the rigor of sudden death. People stood arrested in mid-chore, pail or lota in hand, staring at the crowded threshold, unable to look away, intent on absorbing the impact of what had happened there.

A wail burst forth as Viegas’ guide entered. A few minutes later the crowd parted to let the doctor in.

The woman had been dead more than an hour. Her features were contorted in agony. There was a trace of bloody froth on her slack lips.

Viegas went through the formalities with mechanical precision. He advised the husband to let him know if anyone else in the household developed a similar fever. The young man knelt at the bedside, an immoveable effigy of grief. There was little point in talking to him.

Viegas hurried back. Forgetting his Raleigh, he jumped into a gharry instead and urged the man to whip his horse. What was he hurrying for?

The answer awaited him at his gate.

The Marwari was back. His nephew was worse. He had developed a swelling in the very place Doctor Sahib had asked him to look out for.

Viegas rushed into the house for supplies. When he returned, he found the Marwari had paid off the gharry. His own carriage was at the doctor’s disposal, he said. Not the rekla this time, it was a carriage drawn by a pair of magnificent greys. Viegas got in gratefully.

As they set off at a brisk canter, the Marwari leaned forward earnestly. ‘Fevers come and go. But people don’t die like this.’

‘What do you mean?’ Viegas was startled.

‘Sahib, I’m not a doctor like you, and I should not presume to tell you what you already know. In the past month more than fifty have died in my neighbourhood. Hale men and women, every one of them. Rich ghee-fed Marwari Jains like myself, not pathetic starvelings of the bazaar. Then, there are rumours.’

‘Rumours?’

‘From the docks. The godowns are full of dead rats.’

‘Stop the carriage!’ Viegas’ voice cracked like a whip and the horses jolted to a halt. Collecting himself, he spoke rapidly. ‘I have my suspicions—have you heard of the bubonic plague?’

‘I read the newspapers, Sahib. And the port has news from Hong Kong.’

‘I’d like to consult Dr Blaney—he’s our senior-most physician.’

‘By all means.’

‘Wait! Today’s Sunday. Dr Blaney doesn’t consult on Sundays. I can confer with Dr Cowasji instead. If we can call at his residence—’

‘Direct me!’

Dr Cowasji was midway through a very British breakfast when Viegas was admitted by the bearer. Courtesy demanded he join his host in a cup of Darjeeling, although he had no stomach for pleasantries this morning.

Mrs Cowasji handed him a cup with a judging look. Did she expect him to ‘saucer and blow’ like a native? Her smile was enough to chill the tea.

Dr Cowasji sized up the fee with a glimpse from his window and graciously agreed to confer. As they walked to the carriage, Viegas mentioned his suspicion.

‘Plague?’ Cowasji laughed. ‘My dear Viegas, have you had a drop too early in the day? Germs are all the fashion, I hear. You know my nephew—’

‘Yes, Dr Surveyor. He’s another reason for my wanting your opinion on the case. I hear he’s doing marvelous work at the College.’

‘Marvels? You can call it that, if you like. Fiddling around with glassware in a laboratory! All this talk of germs hasn’t got us any closer to curing a fever. Yes, my nephew is an intelligent fellow.’

It was a couple of miles to the patient’s house. Before Dr Cowasji’s regal calm, the Marwari’s conversation dried up. Cowasji thawed a little as they stopped before an imposing villa. Rather grandly, he waved Viegas ahead. It was his patient, after all.

The boy was worse, much worse.

The fever had raged relentlessly all night, he was delirious now and his responses were slurred and incoherent. Viegas didn’t need to turn down the bedclothes, the boy’s bubo glared at them, angry crimson from the recent application of a redhot iron. But the boy was past feeling even that inhuman cruelty. All his discomforts were subsumed in a torment that he could no longer locate.

Viegas felt the kind of awe he usually reserved for the overture to Handel’s Messiah, when every note of his violin brought expectation and alarm.

The boy’s heart raced in a gallop that would tire very soon. Already his breathing was shallow.

Viegas placed his hand on the boy’s forehead. For a moment the tortured eyes engaged his own. In that split second the haze lifted and the boy focused on Viegas a look that would haunt and torment him for the rest of his life. There was no pain in those eyes, no piteous appeal for relief. There was only—command. Viegas felt a burden lift. All he had to do was obey.

He took the boy’s hand and felt the fingers curl weakly over his own.

Viegas was about to speak when he heard Dr Cowasji pontificate over the branding of the bubo. ‘An excellent measure,’ he said. ‘As you can see, that’s a septic gland.’

Viegas bit back his words. Yes, it was septic, but—

‘Do not, I beg of you, mention that dreaded word, my dear chap,’ Cowasji said in an undertone. ‘For heaven’s sake don’t call it a bubo.’

‘I would still like Dr Blaney’s opinion.’ Viegas drew the Marwari aside. ‘Will you send your carriage for me at eight sharp—if your nephew should survive the night?’

The boy’s mother, overhearing, shrieked in anguish. It took several minutes of earnest patter from Dr Cowasji to reassure the family.

Viegas looked in vain for a gharry, then walked home in the stifling heat. The rest of the day mocked him with its frivolities. Feigning a headache, he shut himself in his study. He refused dinner and stayed up long after the household was asleep. He walked through the silent house, knowing its tranquility would shatter before Sunday came around again. He knelt at the children’s bedside and tried to pray, but no words came. Instead, the notes of the Messiah welled up in his brain.

He was despised and rejected of men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief. Surely, the words of the prophet Isaiah applied to him alone.

He was certain that if the boy lived, the Marwari would call Cowasji and not him. Viegas was just as certain the boy would not survive. He would have to find out in the morning. And then, no matter what, he would have to act.

The clock had struck three when he finally fell asleep.

Captain’s frenzied barking woke him. It was still dark, just past six. The Marwari’s carriage was at the gate.

The man emerged heavily. With folded hands he said, ‘The plague is with us.’

He remained by Viegas’ side all morning. Funeral arrangements had been made, his brother had arrived late last night. He was no longer needed at home. His flabby face was set in granite obstinacy.

‘There’s no time for grief,’ he said coldly, averting his eyes when Viegas murmured his condolences. ‘It is the plague and what are we going to do about it?’

Neither of them mentioned the number of deaths in Canton, in Hong Kong. Neither of them had encountered plague before.

There was no time to lose. The plague must be brought to public notice.

‘That’s not going to be easy with people like Dr Cowasji,’ the Marwari said. ‘What about this Dr Blaney you spoke of? Will he understand?’

Viegas shrugged. ‘Nobody will understand. Not without proof. No doctor in Bombay has ever seen the plague, not even Blaney.’

‘What kind of proof? We must produce that proof. Now! Quickly!’

Viegas nodded. It was the only way.

At eight o’clock, he sent the Marwari to the Petit Laboratory.

The Marwari did not return till nearly ten.

‘Dr Surveyor is with me,’ he said. ‘And there is another case for you, doctor, so perhaps—’

Viegas was in the carriage before the man stopped talking.

Dr Nusserwanji Surveyor was a serious young man with gentle eyes behind very thick spectacles. After his polite greeting, he fell silent. His principal interest seemed to be his beard. He kept worrying it as if to encourage it to greater exuberance. One arm protectively circled a large leather box, which Viegas concluded, was his portable laboratory.

Viegas was surprised by their destination. He had imagined the patient belonged to his guide’s community, another ‘rich ghee-fed Marwari.’

The carriage had stopped near the Port Trust Bridge. Just beyond was a group of lean-to shanties. Into one of these wretched hovels, the Marwari stuck his head. Dr Surveyor had opened his portable laboratory and was impassively setting out syringes and test tubes.

For the first time, Viegas gave voice to his worry. ‘Do you believe the plague is caused by a germ?’

Dr Surveyor’s eyes shone. ‘I’m going to find out.’

‘But, are you certain about germs? Bacilli? Do they definitely cause disease?’

‘Cholera was not enough to convince you, sir? Did you not vaccinate your patients?’

‘I? No, no. Never! We don’t see so much of it in the city, never do. It’s made the Russian quite famous, though.’

‘Professor Haffkine’s work is not nearly as well known as it should be,’ Dr Surveyor responded warmly. ‘It would be a great privilege to work with him.’

‘He is no longer welcome in Paris, I hear. Nor in his native country.’

‘For the service he has done us, I consider him my countryman.’

‘I honour the sentiment,’ said Viegas, ‘but surely one cannot ignore—’

‘A scientist must ignore everything irrelevant to science. Dr Haffkine is not a good scientist, he’s a great one.’

Viegas smiled. A hard case of hero worship, if ever there was one.

The Marwari returned, looking doubtful. ‘The patient is very badly off from what I gather. I’m not sure if the test can be done.’

‘Leave that to me,’ Viegas picked up his bag and set off towards the hovel. Surveyor followed him.

The Marwari was not wrong.

The woman was in extremis. Two frightened children were huddled in a corner, sobbing in quiet misery. The man at the bedside busied himself with changing the damp cloths on the sick woman. Viegas placed a hand on his shoulder. He rose, and again Viegas was startled to see in his eyes that same look of cold command he had noticed in the dying boy.

I must be losing my mind, he thought. Aloud he said, ‘Your wife is dying.’

‘Have you brought medicine to save her?’

‘I have brought medicine, but it may not save her.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because I don’t know what is making her sick. I can give her the right medicine only if I find out.’

‘Find out, then.’

‘The disease is in her blood and in this painful swelling.’

‘I don’t need to hear that from you, I know that already.’

‘So I will have to look at her blood and at the swelling.’

The man nodded and stepped out of the hut, taking the children with him.

The bubo, about the size of a lemon, was red and shiny. When Surveyor plunged in a needle Viegas expected a gush of pus, but all that appeared in the syringe was a clear, mildly blood-tinged fluid.

The Marwari had joined them, and he bent eagerly over Surveyor, watching as he made smears of the fluid on glass slides.

Viegas had lost interest. He did not think anything would show up on the slides. The woman would die without anything to relieve her. The trust in the husband’s eyes made him feel a thorough charalatan.

‘How long since the children have eaten?’ he demanded roughly.

The man flinched, but answered sullenly, ‘They’re all right.’

‘No. They’re not. Get them a meal now, and feed yourself as well, if you don’t want to get the same fever as your wife.’

‘The money’s for her medicine.’

‘So you’re the doctor now? Come back with some food in five minutes and I’ll have the medicine ready.’

The man took the rupee unwillingly, but the children’s faces had brightened. They were the same age as his own. He reached into his back pocket—he usually stored some candy there for his children to discover, but with all the confusion over the weekend, he had forgotten all about their little game. There—his fingers closed gratefully over a couple of lollipops, and he held them out to the two children.

When they made no move to take the sweets from him, he bent down and lifted them up, quite forgetting his natty shirt. They clung to him, burying their heads in his shoulder. How thin they were, how frightened. If the plague hit them they wouldn’t last a day. Suddenly, Viegas wanted to flee with them, to spirit them away from this hut and its dismal occupant.

The father came back with some food and Viegas set the children down gently. This time they took the lollipops, and trotted off, clutching their treasures.

‘Come around at three if you’d like to see the slides,’ Surveyor said.

Viegas went through the morning in a daze. At three he was in Surveyor’s laboratory, peering into the microscope.

‘Plague bacilli,’ Surveyor said. ‘Note the shape. Bipolar, like safety pins.’

Viegas nodded, but silently thought the pictures in last month’s Lancet had been much more convincing. ‘I better notify,’ he said uncertainly. ‘What do you think? You’re convinced these bacilli cause the plague?’

‘Yes.’

Viegas shook his head. These scientists had no idea what an outbreak meant. They had nothing to do with human lives, all they knew were specks of red and blue that they believed caused disease. Alone, his word stood for nothing. He would never get it across the Indian Medical Service.

‘I’ll talk this over with Dr Blaney,’ he said.

Surveyor looked at him with dislike. ‘Dr Blaney will judge his own patients, sir. You’ve diagnosed three cases. I’ve proved one. More than fifty people have died of the same symptoms in this locality. What more are you waiting for?’

Dr Viegas flushed angrily, and left.

The truth was, he had written the letters of notification already. They were waiting on his desk. He had meant to send them in irrespective of Surveyor’s bacilli. Not for an instant had he doubted his clinical diagnosis. It was this ‘germ business’ he was skeptic about, cholera or no cholera.

The Marwari looked up eagerly as Viegas returned to the carriage. ‘Did you see it? The plague germ?’

There was little point in explaining his worries to this man who only wanted to help. ‘Yes, it is the plague, beyond question. I will make the official complaint. I have the letters ready. Will you take them?’

‘I am at your service. Today and every day until we’re rid of this pestilence.’

They drove in silence, each man seething with fears he dared not voice.

The letters were delivered.

Five days later, on 23 September 1896, a Standing Committee reviewed Dr Viegas’ findings.

On 29 September, Lord Sandhurst, the Governor of Bombay, sent a telegram to Lord Elgin, the Governor General of India, notifying him of an outbreak of plague in Bombay city.

Excerpted with permission from ROOM 000 - Narratives of the Bombay Plague, to be published by MacMillan in January 2015.

Surgeons Ishrat Syed and Kalpana Swaminathan write together under the nom de plume of Kalpish Ratna

Photographs by Ishrat Syed