This simple lament of a lost harvest is a weapon the Chhattisgarh Police has recently deployed in its fight against Maoism. It is one of the several songs being performed by a first-of-its-kind troupe put together by the police in Sukma district, the Police Natya Chetna Manch. The authorities hope that the appeal of songs performed in local languages will achieve what the fear of the bullet hasn't – win back territory and minds from the left-wing guerrillas.

Local languages

This outreach programme is part of an effort started by the Chhattisgarh Police two years ago to make space for indigenous languages in its arsenal. It is an acknowledgement that relying on Hindi to relay the state's message to tribals has not worked.

How could it when Hindi remains a foreign language in vast areas of this state where it is the official language? While district-wise distribution of language data from the Census is not public, Hindi's limited reach here can be surmised through available data on literacy, given that education is offered only in Hindi in Chhattisgarh. The 2011 Census literacy data shows that Dantewada, Bijapur and Sukma districts, all of them at the centre of the Maoist maelstrom, have literacy rates in the low- and mid-thirties. While few outside the formal education system have a chance to learn Hindi, the abysmal education standards here means that even many who have attended school fail to learn the language. It seemed inevitable that the police would have to adopt tribal languages if they wanted to be effective.

Last month, the state police's first radio jingles in local languages went out on air. Six spots in Gondi, Halbi and Chhattisgarhi have started playing on All India Radio in the state, seeking to undermine the appeal of the Maoists. "Maoists have blocked development that should rightfully belong to you," one of them says. "Question them. You take a step, the state will take four."

Another provokes listeners to ponder on the cost of this conflict. "Maoists have been surrendering constantly… Maoism has no future," it says. "Think, the Maoists will go back along with their families to their villages with fat compensation money but who will pay for the lack of development that has come about because of them?"

Adopting local languages has also helped the police create a counter-narrative to the stereotypes associated with the security forces here, one that is built around their hauteur and swagger and, worse, recurring stories of encounter killings. The police are seeking to change some of that by presenting a more humane side. Performances have been organised at weekly haats, a central feature of the tribal economy and culture, and in interior villagers. Seeing cops sing and dance and that too in their languages has helped bring about some rapprochement. The response, claims Sukma Additional SP (Naxal Operations) Santosh Singh, has been "awesome". "People didn't expect us to have this softer side, didn't realise we could talk back with politeness," he said. "They now listen to us more attentively."

Song and dance

Police Natya Chetna Manch troupe

As it turns out, the police found inspiration for this dramatic strategy in a similar troupe run by the Maoists. In fact, some of their members are surrendered rebels who worked for the Maoists' Chetna Natya Manch. This troupe is a vital part component of the Naxalite public outreach machinery. Its repertoire includes songs that criticise the state's exploitation of tribals and their resources, and celebrate indigenous traditions. The police decision to ape the Maoists is recognition of the stunning success the rebel cultural troupe has notched up.

Dantewada, Bijapur and Sukma are areas where electronic forms of entertainment (even radio) are difficult to come by, and programmes in local languages even less so. As a result, performances by the Maoist manch fill an enormous entertainment void. In addition to the cultural performances in local languages, the Maoists also offer education in Gondi, a language that is spoken by close to three million people but not yet recognised by the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution. (Sanskrit, with just over 14,000 speakers, has that status.) "The Maoists have used tribal languages much better than we have," admitted Singh. "This explains their stronghold."

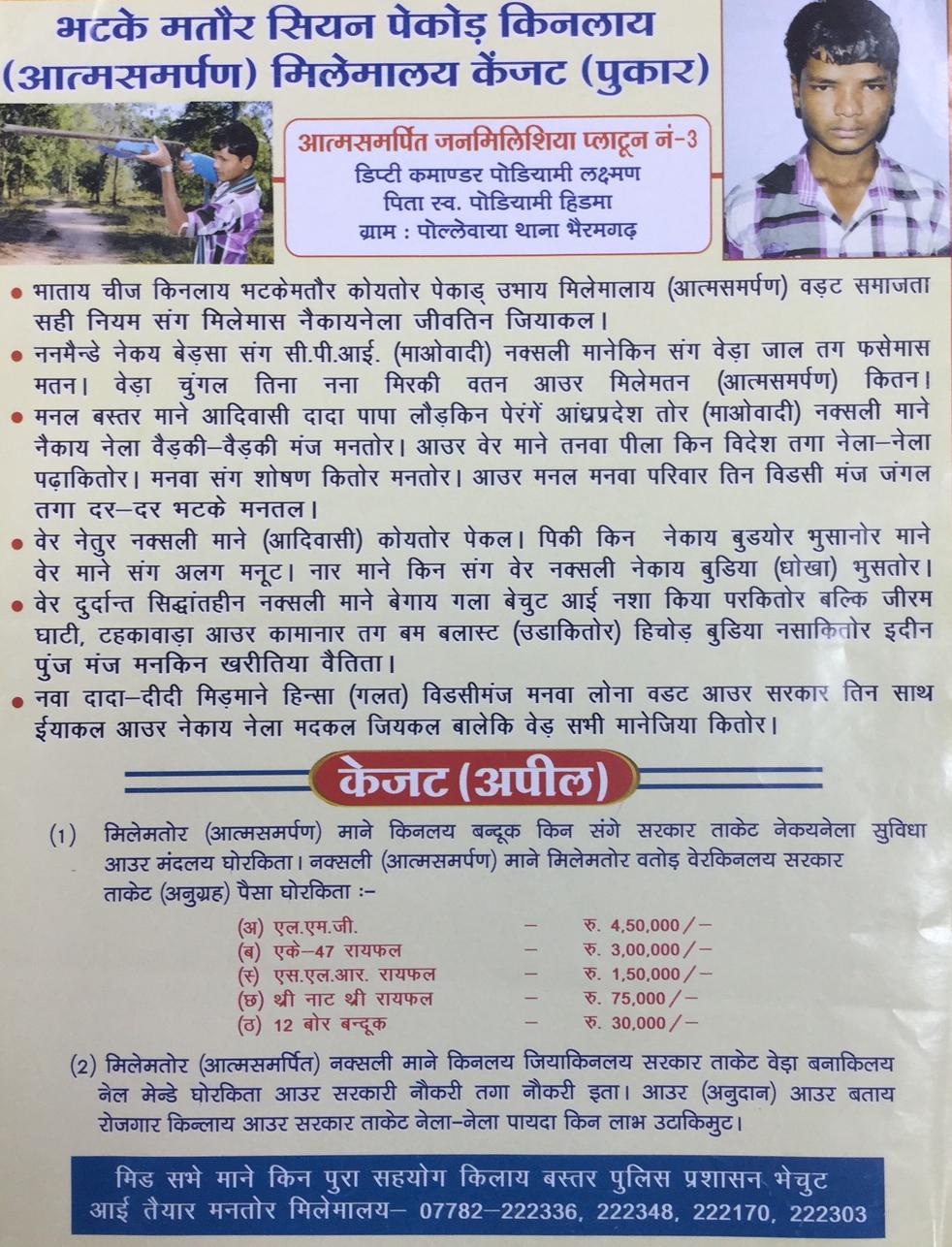

To attempt to loosen that hold, local languages such as Halbi, Gondi and Dorli have been part of the curriculum at training institutions for both constables and officers over a year. Anti-Maoist posters featuring appeals by surrendered guerrillas are also being printed in local languages. They are accompanied by recordings of such appeals in faraway villages.

But does the adoption of local languages represent a real change in the relationship between the police and adivasis in Chhattisgarh? Many will say no. If the relationship has to change from one of fear and disdain, sincere steps need to be taken to make the law and order machinery more just and accessible for tribals. However, the recognition of tribal languages and cultures by the police, which often is the only state representative in these areas, is a step forward to giving adivasis greater rights.

Debarshi Dasgupta is a National Foundation for India Media Fellow, working on the linguistic aspects of the Maoist conflict.