The infection, caused by the HepC virus, is a slow killer that destroys the liver but most people are unaware they are infected because there are no symptoms in the initial stage. In the long-term however the effects are life-threatening – cirrhosis, liver cancer and liver failure. Every year, chronic Hepatitis C takes 500,000 lives worldwide.

For months, Coelho, a resident of Gurgaon, tried hard to access Gilead’s life-saving medicine, which was then not available in India. He wrote to the company asking for a discounted rate through its patient support programme, he wrote to health activists seeking their intervention, and he wrote to government departments for permission to import the crucial drug. Sovaldi is the first oral treatment for HepC, a once-daily pill which, taken along with a certain class of antiviral medicines, offers a new lease of life. Earlier treatments, based on a combination of injections and pills, had to be taken over a year if not several, and caused terrible side effects.

Unable to procure the medicine, Coelho died in January this year. His death came around the time hope had appeared on the horizon. Gilead’s patent claim on sofusbuvir was rejected by the Indian Patent Office in January. Theoretically, this means that pharmaceutical companies can make hugely cheaper generic versions of the drug instead of waiting for the patent term to expire, which is usually a period of 20 years from the date of patent application. In practice, this is unlikely to make a big difference.

Pharmacy of the world

Generic versions of medicines like sofusbuvirare are critical for patients because they bring costs down and save millions of lives. A study by the humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières shows that generic competition in first line anti-retrovirals used to treat HIV/AIDS patients brought down prices by as much as 99% – from $10,000 per patient per year in 2000 to just $70 a decade later. And the prices are still dropping.

This stupendous reduction was possible because the anti-retrovirals were not under patent in countries with drug production capacity, primarily India, Brazil and Thailand. It was the rapid production and export of inexpensive medication during the AIDS crisis of the 1990s and 2000s that earned India the sobriquet of “pharmacy of the world”.

But with the new generation cancer and viral drugs, this is not happening.

In accordance with the World Trade Organization’s requirements, all members, barring the least developed countries, have enacted patent laws. That’s the primary reason. The other is that the innovator pharmaceutical companies have introduced tiered pricing. This means drugs are priced lower in different countries based on national income while the market price is charged only in developed countries. But WHO also warns that this marketing strategy variously described as ‘differential’, ‘preferential’ or ‘discounted’ pricing does “not necessarily result in affordability or equitable access to a product”.

A Gilead spokesman told this writer that currently Sovaldi is available in India only on a Named Patient basis as its compassionate use programme is called. “We hope to have Sovaldi available in India as soon as possible and we are working as quickly as possible to make that happen.” Gilead recently received approval for Sovaldi in India and it hopes to launch by mid-2015. The drug will be priced at $300 per bottle (28 tablets) here, which means the three-month course will cost $900.

Signing restrictive agreements

However, generic competition is not likely to bring down prices further because Gilead has entered into voluntary licensing agreements with Indian generic companies, effectively tying up the market although the company presents it as a humanitarian gesture. These agreements, it says, will provide the lower priced versions to more than 100 million people in 91 countries. The licensed companies are given Gilead’s technology to manufacture large volumes of sofosbuvir in return for 7% royalty.

So what this means is that although Gilead has lost one of its patent claims on sofosbuvir in India, as in Egypt which had also rejected it, the US drug major has pre-empted any real competition by locking top Indian producers into restrictive voluntary licensing agreements.

Gilead initiated this strategy about eight years ago when its patent claim on an HIV drug, Viread, was rejected by India’s patent office. It then entered into VL agreements with generic manufacturers although it held no patent on Viread.

Gilead’s strategy is “tantamount to a landlord offering to rent and receive payment for a property for which his ownership has not been determined,” according to lawyer Tahir Amin, co-founder and director at the Initiative for Medicines, Access and Knowledge or I-MAK, which is one of the four organisations that has challenged the sofosbuvir patents.

In the instance of sofosbuvir, Gilead signed VL agreements with several companies in September 2014 even before the patent challenge was heard. Its biggest coup came last week when Natco Pharma of Hyderabad dropped its patent suit against Gilead and instead joined the band of eight companies that had earlier signed up a VL agreement. This has shocked health activists and lawyers who believe there is a strong case against the sofosbuvir patents. Natco refused to answer questions asked on the reasons for this unexpected turnabout.

Natco’s move is also surprising because it has been in the forefront of legal challenges against the weak patent claims of innovator companies. But Natco insists there will still be competition. Company secretary M Adinarayana said: “There will be competition. Natco’s price is Rs 19,900 (for a bottle). We are free to choose our own price.”

Asked if the price would not have been lower without the VL agreements, given that the patents were revoked finally, the company said it had no comment. In just over a week of signing the VL deal with Gilead, Natco got the regulatory approval for sofosbuvir from the Drugs Controller General of India.

Still unaffordable for millions

Given the terms of the licence, analysts say it is unlikely that prices will dip below the $300 per bottle price. Tahir Amin said, “Gilead is using the VL model to co-opt all its competitors by giving them a small slice of the pie.” Amin points out that many, if not most, of the 91 countries in the licence agreements do not even have a HepC programme or would not be able to afford the drug unless it is sold for around $200 for the full 12-week course. “Gilead is keeping the bigger middle income markets for itself, where it will charge approximately $7,000-9000, and these are the countries where the burden is highest, more so given the poorer populations in these countries,” said Amin.

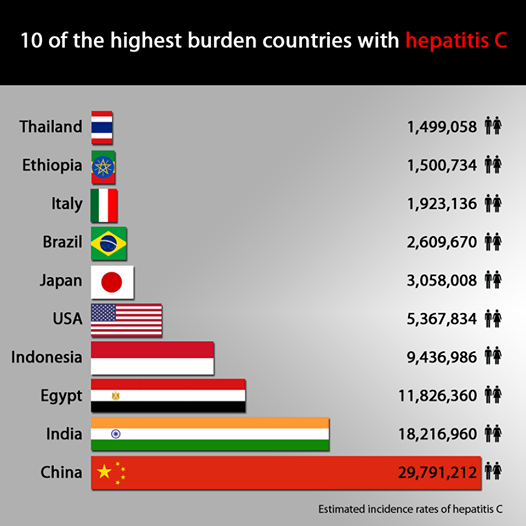

Amin is referring to countries such as China (see chart below), which has the highest incidence of HepC cases, close to 30 million, but is excluded from the VL ambit. In all, 50 million infected people in 51 middle-income countries will be denied the generics made by Indian companies. “It’s also worth noting that many of these 91 countries included in the licence don’t even have patents,” Amin said. “So that is why India is important for Gilead to control because that is where its competition will come from.”

Credit: MSF Access Campaign

It could be argued that the $900 price is a tremendous discount on the eye-popping $84,000 tab in rich countries. But these prices have once again ignited a critical debate about the morality of drug patents and the pricing of new life-saving medicines, a debate that first erupted in the 1990s when the AIDS epidemic peaked. In the US senators have been critical of Gilead’s pricing because it has accounted for the single largest jump in costs in Medicaid, the nationalsocial healthcare programme. In the UK, the National Health Service has put Sovaldi on hold because it will be unable to the foot the £1 billion bill for every 20,000 people treated.

“Even $300 is too expensive for the average India, let alone the poor,” pointed out Eldred Tellis, director, Sankalp Rehabilitation Trust, a patient group that joined the patent opposition litigation in January. He argues that if people living with HepC virus across the world are to access affordable treatment “Gilead should not be allowed to manipulate competition to further their profit motives”.

Hope and disappointment

There are around 12 million HepC patients in India, and most cannot afford even part of the discounted price. Ask Shadaab Hassan of Kolkata, who has been put through the wringer on account of his acute HepC condition. Hassan is a good example of the trauma that HepC patients suffer, when their condition deteriorates rapidly and medication to control it is unaffordable. Hassan’s downward spiral started in 2006 when as a 26-year-old he was diagnosed with HepC. It was a bombshell for the young call centre employee. There were weekly injections of pegylated interferon, which set him back Rs 14,000 a shot, apart from costly screening tests.

But weeks of that drug did not help and he got really sick and slipped into a coma. That is when doctors discovered he had liver cirrhosis. With friends and family rallying round, Hassan had a liver transplant in November 2011 although “the cost was obscene”, he said. His brother donated part of his liver and Hassan pulled through, only to find that HepC was back in three months’ time. “There is always recurrence of the infection; it’s just a matter of time. But the doctors never tell you that.”

Yet, Hassan has been more fortunate than Coelho because he is now on Gilead’s compassionate use programme, which provides free medication. That took a huge effort. For the past five years he had been hearing about new drugs called direct acting antivirals that promised a cure. He applied to several companies developing these drugs but got no answer. In desperation he wrote to hospitals in the US to take part in clinical trials of the drug but was told that all spots were filled.

Speaking to me, midway through his current treatment with sofosbuvir, a delighted Hassan said, “It’s magical. It’s a new lease of life for me.” He is now working as a marketing professional after a long, long hiatus and is expecting to lead a relatively normal life soon.

But for millions of other HepC patients here, there may be little reprieve.

As the patent case winds its way through the legal labyrinth, there is both hope and disappointment. The hope springs from the belief that patent challenge to sofosbuvir is strong. The pre-grant opposition filed by I-MAK says the drug is not new and that the patent is based on old science that was disclosed in a 2005 application made by Gilead to India’s patent office. The disappointment stems from the fact that India’s top generic companies have caved in and opted for the safer option of VL agreements.

The saddest part is that sofosbuvir can in future be manufactured at a fraction of the costs charged by Gilead. A study by Liverpool University shows the drug could be produced in India for as little as $101 for the full three-month treatment. As Andrew Hill, senior research fellow at the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics who led the study, emphasised: “That’s roughly $1 per pill, which is a big improvement over the $1,000 per pill Gilead is charging in some countries.” Indeed, it is.