This was meant to be the presidential address at the annual conference of the Jat-Pat Todak Mandal (Forum for the Break-up of Caste) in Lahore. The Mandal, considered a “radical” faction of the Hindu reformist Arya Samaj, was founded in 1922 by mostly Hindus of privileged castes. Its annual conferences had previously been addressed by members of society whose names bore the entitlement of caste and privilege: Swami Shraddhanand, Motilal Nehru, Bhai Parmanand, Rameshwari Nehru, Sri Ramananda Chatterjee, Sri Satyananda Stokes and such. No Dalit had been invited till then.

What would Ambedkar end up saying?

In 1936, having invited Ambedkar, the Mandal’s leaders were unsure of what he would say. After all, in October 1935, at the Yeola Depressed Classes Conference, he had declared: “I had the misfortune of being born with the stigma of an Untouchable. However, it is not my fault; but I will not die a Hindu, for this is in my power.” The nation was in a tizzy. Ambedkar had effectively declared a spiritual war on Hinduism, disgusted as he was with the man Hindus had come to revere as a Mahatma ‒ Mohandas Gandhi.

And so the Mandal asked for Ambedkar’s address in advance, and predictably it found many portions of the text objectionable. Har Bhagwan, one of the Mandal’s men, wrote to Ambedkar on 22 April 1936: “You have also unnecessarily attacked the morality and reasonableness of the Vedas and other religious books of the Hindus…” They suggested he drop all references to “Veda”. More importantly, Ambedkar had said, in passing: “This would probably be my last address to a Hindu audience.”

As it turned out, Ambedkar had more or less anticipated such a conservative response from a group that was posing as a radical one. In the very opening of his speech, he had written:

I am sure they will be asked many questions for having selected me as the president. The Mandal will be asked to explain as to why it has imported a man from Bombay to preside over a function which is held in Lahore. I believe the Mandal could easily have found someone better qualified than myself to preside on the occasion. I have criticised the Hindus. I have questioned the authority of the Mahatma whom they revere. They hate me.

Ambedkar wrote back to Har Bhagwan without mincing words:

…I would not alter a comma, that I would not allow any censorship over my address, and that you would have to accept the address as it came from me. I also told you that the responsibility for the views expressed in the address was entirely mine, and if they were not liked by the conference I would not mind at all if the conference passed a resolution condemning them.

The speech was never given

Ambedkar’s speech was denied the audience it was meant for. When he published the speech at his own expense, he chose to make public his entire correspondence with the Mandal, thus offering a prehistory of the speech in the very first edition. He perhaps had hoped to shame the Mandal and Hindus who pretended to be reformers.

On reading this book, Gandhi began a “review” in his journal Harijan thus: “He has priced it at 8 annas, I would suggest a reduction to 2 annas or at least 4 annas.” Gandhi seemed to have no issue with the fact that primary membership to the Congress party also cost four annas.

AoC was soon reprinted (1937), and translated into six languages. The rest is history. And today, it is worth reflecting a little more on this history.

The struggle to publish

In his own lifetime, it was a struggle for Ambedkar to publish his writings. Though his usual publisher Thacker and Co. in Bombay published many of the books, it was difficult to raise money for works no-one seemed keen to publish. For instance, he did not have the resources to print The Buddha and His Dhamma, what may have been his last book. The story behind this, which I had recalled on another occasion, is still worth recounting.

On September 14, 1956, exactly a month before he embraced Buddhism with half-a-million followers in Nagpur, he wrote a heart-breaking letter to Prime Minister Nehru from his 26, Alipore Road residence in Delhi. Enclosing two copies of the comprehensive Table of Contents of his mnemonic opus, The Buddha and His Dhamma, Ambedkar swallowed his pride and sought Nehru’s help in the publication of a book he had worked on for five years:

The cost of printing is very heavy and will come to about Rs 20,000. This is beyond my capacity, and I am, therefore, canvassing help from all quarters. I wonder if the Government of India could purchase 500 copies for distribution among the various libraries and among the many scholars whom it is inviting during the course of this year for the celebration of Buddha’s 2,500 years’ anniversary.

Nehru replied to Ambedkar the next day, saying that the sum set aside for publications related to Buddha Jayanti had been exhausted, and that he should approach Radhakrishnan, chairman of the commemorative committee.

It is another shame that Ambedkar was kept out of the committee to observe the 2500th birth anniversary of the Buddha. Nehru also offered Ambedkar some gratuitous business advice: “I might suggest that your books might be on sale in Delhi and elsewhere at the time of Buddha Jayanti celebrations when many people may come from abroad. It might find a good sale then.”

The Prime Minister was asking his former Law Minister, the man who oversaw the drafting of the Indian Constitution, to set up a stall and hawk his own books. It is for such arrogance, too, that Nehru is much loved by India’s court historians. Radhakrishnan is said to have informed Ambedkar on phone about his inability to help him.

Posthumous sales

[Ramesh Shinde, collector of Ambedkariana, with the first edition of the The Buddha and His Dhamma.]

It is not surprising that Ambedkar’s posthumous publications easily outstrip the works he could manage to publish in his own lifetime. Among these are Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Ancient India, Philosophy of Hinduism, and Riddles in Hinduism. When the last-mentioned work was published, the Shiv Sena protested and the Maharashtra government banned the work in 1988.

In all subsequent editions of Volume 4 of the Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches series, the Maharashtra government, which claims proprietorial rights over all Ambedkar’s works, carries this caveat: “Government does not concur with the views expressed in the chapter.” The chapter in question is titled The Riddle of Rama and Krishna. To this day, the Maharashtra government damns its own publication while damning Ambedkar.

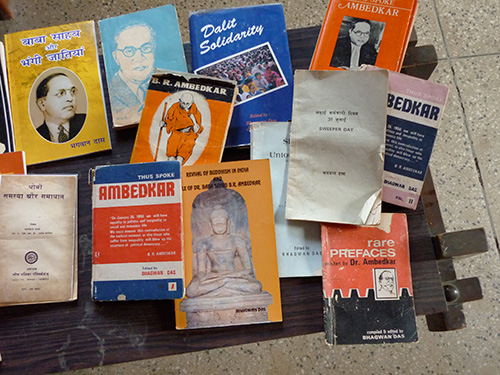

In such circumstances, how have Ambedkar’s writings been kept alive? Several Dalit writers and scholars, and Ambedkarite publishers in small towns and cities of India, many of whom have, with no resources other than passion and political will, strived to make public the writings of Ambedkar after his death in 1956. Among them two are worthy of special mention: Lahori Ram Balley and the late Bhagwan Das.

Balley established Bheem Patrika Publications in Jullundar, and since 1958 he has been publishing Ambedkar’s works well before the Dalit movement in Maharashtra coaxed the state government into doing so. Balley’s efforts were documented in Outlook newsmagazine a few years ago:

[Balley] has joined every single campaign directed at getting more access to Ambedkar’s writings for people. He counts among his achievements the rescue and publication of scores of his speeches and writings, many previously unpublished, that were locked in six trunks and in the custody of the Bombay High Court for almost two decades after his [Ambedkar’s] death. “We appealed to the courts and to Ambedkar’s warring children to let us have access to those precious papers which had begun to deteriorate. The All India Samata Sainik Dal, founded by Ambedkar in 1927, had launched a movement to get his unpublished writings published and as a member of the Dal, I joined the effort. The Maharashtra government eventually published the manuscripts in 1979,” he [Balley] says. But by then Bheem Patrika Publications had already brought out several translations of Ambedkar’s classic essay, Annihilation of Caste, based on his undelivered speech for the annual conference of Jat Pat Todak Mandal of Lahore in 1936. (Ambedkar’s family filed a case against him for doing this.)

Bhagwan Das was another man who made it his life’s mission to take the writings and message of Ambedkar to a wider public. Das had worked with Ambedkar as a research assistant in the last years before Ambedkar passed away. He was among the few people I met who had known Ambedkar personally. At Navayana, I published his memoir, In Pursuit of Ambedkar (which comes with an hour-long documentary feature on DVD), and the first of four volumes of his pioneering series, Thus Spoke Ambedkar.

When we remember this day in history, we must also remember those who kept this history alive for us.

S. Anand annotated the critical edition of Annihilation of Caste, featuring an introduction by Arundhati Roy, published in 2014.