From the current solar power generation capacity of 4 gigawatt, it wants to produce as much as 100 GW by 2022 – with a target of attracting a staggering $100 billion into the sector over the next seven years.

On June 22, a fairly sizeable chunk of that goal was met, when Japan’s SoftBank, along with telecommunication major, Bharati Enterprises, and Taiwan’s electronic goods manufacturer, Foxconn, announced plans to invest $20 billion for setting up 20 GW of solar power in the country.

Other firms, including Adani Power, Reliance Power and SunEdison, have also committed investments worth more than $5 billion for setting up solar power plants in India.

But why exactly is the private sector so keen on ploughing billions into building up India’s solar power sector?

For starters, India simply needs more power. Between April 2014 and March 2015, for instance, the country had to deal with a 3.6% deficit in peak hour energy supply (the period when demand for power is significantly higher than

Power requirement in India is estimated to grow at an average of 5.2% during the 10 years between 2014 and 2024, according to a report by Tata Power (pdf). Currently, India requires 1,068,923 million units of electricity annually but the supply falls short by 3.6%.

All of this demand isn’t likely to be met by traditional energy sources. India’s coal-fed power plants – which contribute to nearly 60% of the total production – have been grappling with periodic fuel shortages. Domestic production of coal hasn’t quite kept pace with demand, which alongside expensive imported coal, has made things difficult.

Simultaneously, there’s been a steady decline in solar power prices – on the back of cheaper solar panel costs and lower financing costs – that has made the sector increasingly attractive to investors.

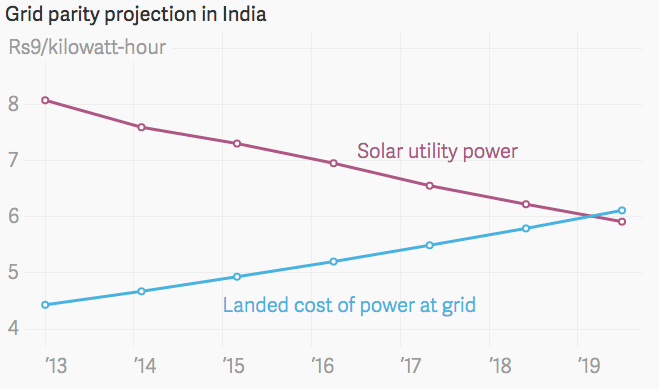

By 2019, according to some estimates, India could achieve grid parity between solar and conventional energy sources. That’ll mean that solar power will cost less than or equal to power from conventional sources.

Some 240 GW of this can potentially come from just two states – the western desert state of Rajasthan (142 GW) and Jammu and Kashmir (111 GW) in the north – while others like Madhya Pradesh and Maharashta could produce over 60 GW each.

The chart below lists the states with the most commissioned solar projects and the amount of power they can potentially produce.

Unlike a number of other infrastructure projects, there seems to be no dearth of land for solar power projects, with more than 467,021 sq km of wastelands in the country.

A report by consultancy firm Mercom Capital Group said that the government’s increased targets have “thrilled the sector, but the industry is pragmatic and realises that while 100 GW looks great on paper, the last five years have resulted in only 3,000 MW (3 GW) in solar installations, with last year’s installations at less than 1 GW.”

Between 2009 – when India had about 0.006 GW of solar power installation – and 2015, the country’s total solar power capacity grew exponentially. But much of that’s been because of the government throwing its weight behind the sector.

“By 2018 several states will achieve parity between grid tariffs for commercial and industrial users and the LCOP (landed cost of power) from utility scale projects, providing an impetus for further growth,” Tata Power’s report said (pdf). A utility scale power plant sells power to electric utilities and not end-use consumers.

“Thereafter,” the report added, “we expect that additions under central and state policies will decline with capacity additions being driven by parity.”

This article was originally published on qz.com.