The plan includes investing Rs 5,000 crore every year up until 2022 to provide vocational training to 400 million young people. This ambitious Skill India campaign of livelihood schemes operates at the central and state levels. It involves the efforts of more than 20 ministries coordinated by the newly established nodal ministry of skill development and entrepreneurship, more than 20,000 industrial training institutes and polytechnics, and more than 3,000 training centres set up by private sector partners of the National Skill Development Corporation.

But, despite such massive investment, vocational training may not alone be the answer to the country’s unemployment problem. That’s because a large number of students who are “placed” after graduating never actually join jobs – and many of those who do, quit soon after to return to their villages.

Partly as a result of such tendencies, a large proportion of rural Indians are underemployed – or in disguised unemployment – despite the official unemployment rate of just 3.6%.

At Pratham, India’s largest educational NGO, we tracked 2,300 vocational training students between April 2014 and April 2015 after they were “placed” – i.e. accepted offers from employers – with jobs. We discovered that 9% of the students went back to their villages directly after training, instead of going to the cities where they were offered jobs.

And of those who did take up jobs, only about half (48%) of the students were still at work three months later. A year later, only about one-fourth (23%) still employed.

The great divide

The fundamental problem is that while vocational infrastructure has been set up in remote areas to combat rural poverty, nearly all the jobs that students are trained for continue to exist in urban areas.

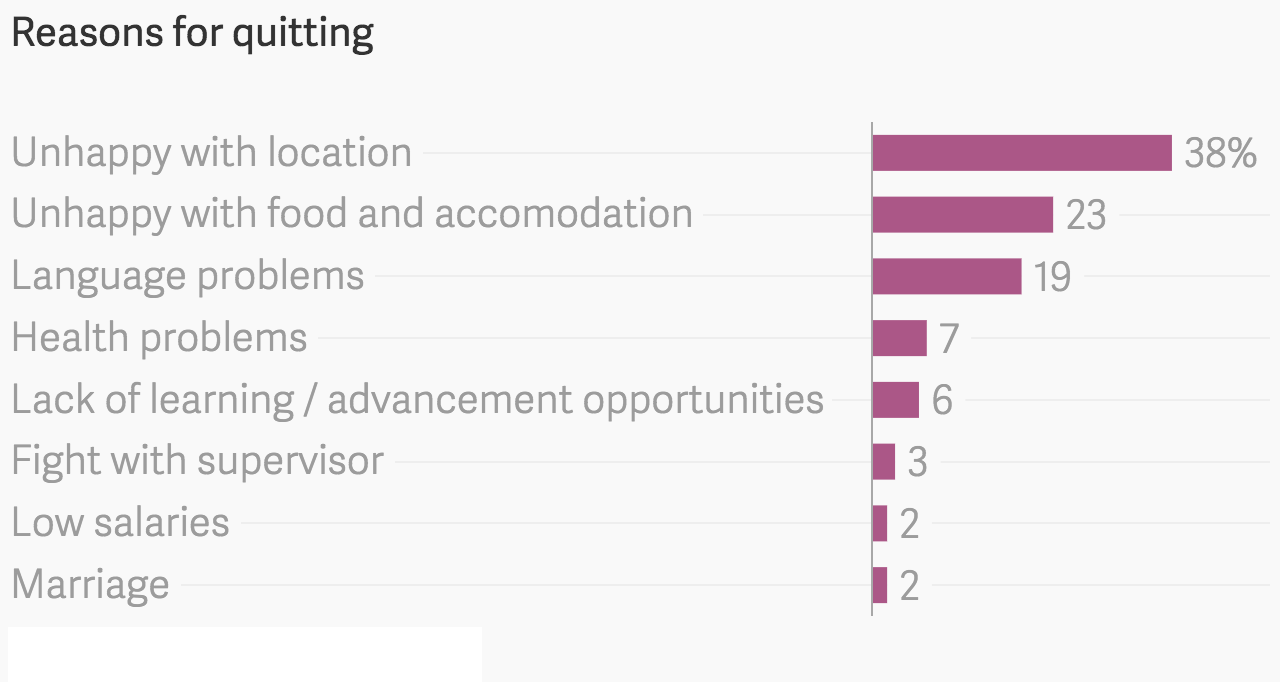

Many of the students we followed had never travelled beyond their village clusters, let alone their districts. So, when they were relocated for jobs, many of them fell ill or suffered from extreme homesickness. The result: Most came home to their villages.

Even though the primary earners of most rural families in India earn an average monthly income of less than Rs5,000 ($76), students willingly gave up jobs in urban areas that offered over Rs8,000 ($122) in order to escape seemingly inhospitable cities.

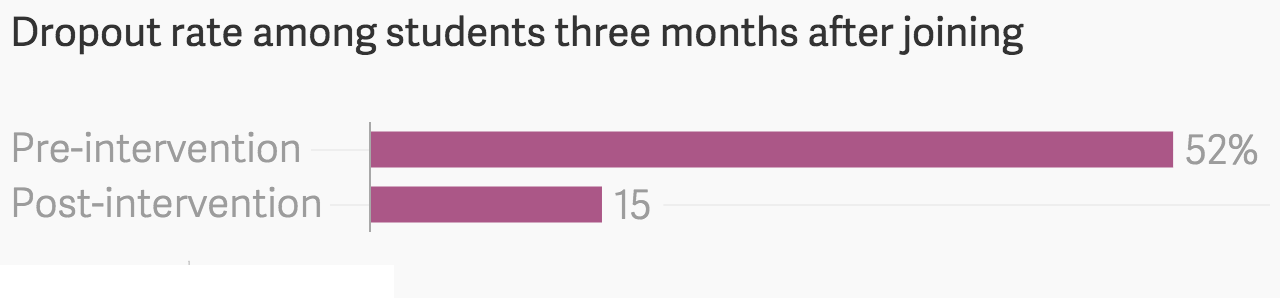

To beat this, Pratham created a network of placement and tracking associates to help students adjust and to reduce dropout rates. These associates did everything from contacting employers to solve problems, including helping students find credible doctors in the new city and sometimes even counselling them on matters of the heart.

The results were dramatic: After six months of setting in place the new process, the dropout rate for a batch of 300 students plummeted from 52% to 15%.

So, even though millions are planned to be ploughed into skill development, what the Modi government also really needs to focus on is mitigating the toils of migration. An army of youth aged between 18 and 30, who may or may not have even finished high school, is being prepared to relocate and join the workforce.

A focus on helping a smooth transition is needed, and attention on preparing the students and their families for the massive change is required. Low-cost urban hostels with cooking facilities for the first few months of relocation would help tremendously.

A first step may be to quantify this reality through a nationwide survey of youth, perhaps in the same way Pratham maps learning outcomes of children through the Annual Status of Education Report. Eventually, the focus needs to be on the number of youth added and retained in the workforce, rather than only trained or placed.

This article was originally published on Qz.com.