The One Rank One Pension scheme will allow retired military personnel pension parity with those of the same rank who retire now. The OROP is expected to have a one-time cost of Rs 8,400 crore, with higher costs in the future. It will benefit 25 lakh retired military personnel. The BJP promised the implementation of the OROP in its election manifesto in 2014. Delays in implementation of the scheme a year after the government was formed, and lack of a deadline on its launch, has drawn flak from military veterans who have been protesting at Jantar Mantar grounds in Delhi for their demands.

The vacillation over higher pensions for ex-military personnel is being seen as an issue that could cost the BJP government politically. However, this and previous governments have done no better on social pensions for a large majority of the elderly in the country. Social pension amounts allocated by the Centre to families below poverty line are too small to act as a basic and regular source of income for those above 60, they cover only half of eligible beneficiaries, and have not been increased in a decade.

Social security beyond job security

The idea of social security, including pensions, originates from the notion that everyone must have protection against vulnerability and deprivation but in practice, it has come to be linked to job security, whether one has a job in the formal or the informal sector.

Under the Directive Principles Article 41, the State is expected to “within the limits of its economic capacity and development, make effective provision for securing the right to work, to education and to public assistance in cases of unemployment, old age, sickness and disablement, and in other cases of undeserved want".

Despite constitutional provisions, India spends only 1.4% of its Gross Domestic Product on social protection. China spends several times more at 5.4%. As per an Asian Development Bank study in Asia and the Pacific, even much smaller countries do better than India on the social protection index, with Sri Lanka spending 3.2%, Thailand 3.6% and Nepal 2.1% of GDP on social security.

Most of the pensions expenditure of the government is borne on account of civil servants that form a very small proportion of the elderly in India. Researchers Charan Singh, Kanchan Bharti and Ayanendu Sanyal have calculated that expenditure on social pension for the elderly in 2010–11 accounted for 0.1% of the Gross Domestic Product and 0.5% of the revenue receipts. The same year, civil service pension expenditure of the government for retired government employees was 3.1% of GDP and 15.3% of the revenue receipts.

Social pensions schemes

The government's largest pensions programme for the poor is the National Social Assistance Programme. Since 1995, the central government has provided small amounts of social pensions to those below poverty line who are above 60 years of age, to widows and the disabled.

Several studies have recorded how even these small amounts provide support to elderly poor in villages, allowing them to afford food, medicines, basic necessities. No large scale instances of leakages or scams have been recorded, with the scheme functioning reasonably well. In 2013, Public Evaluation of Entitlement Programmes survey by researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, recorded that among nearly 900 rural respondents selected at random from the official pension lists in 10 states, 97% were getting their pension and recorded only one case of “duplicate” pension i.e. one elderly person getting two pensions. However, 76% of the respondents said they received pensions in their post office and bank accounts after delays of over a month.

Kunti and Surajman receive monthly pensions of Rs 300 each in Sarguja, Chhattisgarh

Narrow coverage

Yet, the Centre's contribution per pensioner has remained a meagre Rs 200/month since 2006. For widows and disabled, this has stagnated at Rs 300.

In principle, the National Social Assistance Programme or social pension is meant to cover all eligible persons in the below poverty line population – those above 60 years old, widows over 40, and those with over 80% or multiple disabilities, but the freezing of the central allotment has meant that in many states even those eligible cannot get pensions.

Instead of following a universal approach, the Centre gives funds on the basis of the poverty line which itself is pegged extremely low at Rs 32 per person per day in urban areas and Rs 26 per person per day in rural areas. The actual pensions vary as per state policy. So, for instance, Tamil Nadu provides a pension of Rs 1,000, along with 4 kg of free rice. Himachal Pradesh and Rajasthan provide between Rs 400-Rs 750 per month, Madhya Pradesh provides only Rs 175-Rs 275 a month. While a few states such as Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan have allocated additional funds to widen the coverage, in states that do not prioritise this scheme, elderly and the destitute cannot get on the pensions list even if they are eligible. Officials say several states have long “waiting lists” as a result of this. “At present, because the Centre has frozen its allocations and not revised it in years, the pensions scheme does not even cover even half of the total population of those eligible,” said a senior official supervising the scheme.

Funds cut

When the government slashed social sector allocations in the middle of the financial year, pensions were the worst hit, with a reduction of 30%. The government had announced a budget estimate of Rs 10,546 crore for 2.3 crore pension beneficiaries in the financial year 2014-15. In January, in the middle of the financial year, the government slashed this to Rs 7,187 crore under the revised estimate.

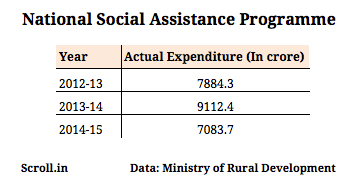

With funds cut, the Ministry of Rural Development did not allocate money for pensions in time to states. This created a deficit of more than Rs 2,000 crore at the state level, which translated into thousands of elderly dependent on these small pensions in poor states such as Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand not getting their pensions for several months, said officials. As a result, actual expenditure on the scheme fell last year from Rs 9,112.4 crore in 2013-14 to Rs 7,083.7 crore in 2014-15.

“The budget was reduced in the revised estimates stage, so there was no money to give to states,” said a senior official at the Ministry of Rural Development. “The second instalment for many states were given this (financial) year. Unless funds are allocated to wipe out the deficit, this will create a cascading effect.”

Modi government takes credit for creating new financial infrastructure – Jan Dhan, Aadhaar, Mobile – for improving subsidy payments including pensions, but a policy decision slashing funds for social sector schemes mid-year has disrupted otherwise functional schemes.

While the non-contributory social pensions schemes is in place, instead of building on it, revising pensions amounts and making it universal, the government has launched a contributions-based pensions scheme, the Atal Pension Yojana. Under this, beneficiaries will get payouts based on monthly contributions over a minimum of 20 years. For instance, a 40 year old must contribute Rs 291 every month for 20 years and a 35 year old will have to contribute Rs 181 a month for 25 years to get a pension of Rs 1,000. Only those between 18 years and 40 years are eligible for this.

Activists who have been demanding an enhanced, universal pension say the government is taking decisions that are designed to exclude the poor. They point out that the Atal Pension Yojana does not say what happens to those over 40 years of age, and it does not say how those working as casual labourers will maintain steady contributions for over 20 to 25 years.

If it is serious about assisting the elderly in fulfilling their basic needs, having a sense of security and well-being, the government will have to reconsider its policy approach and design towards the most vulnerable.