Everybody knows there are not enough female police personnel, but what is the state of those who have been recruited? That's what a new report on the status of women in the police by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative investigates.

“A male officer may be a fool of the highest order but will be taken as a good officer,” a woman quoted in the report said. “The threshold of credibility is much lower for men. Women have to prove themselves.”

In a series of interviews, surveys and discussions in four states, Rajasthan, Meghalaya, Haryana and Kerala, the report highlights the challenges for women that pervade the entire force.

Getting in

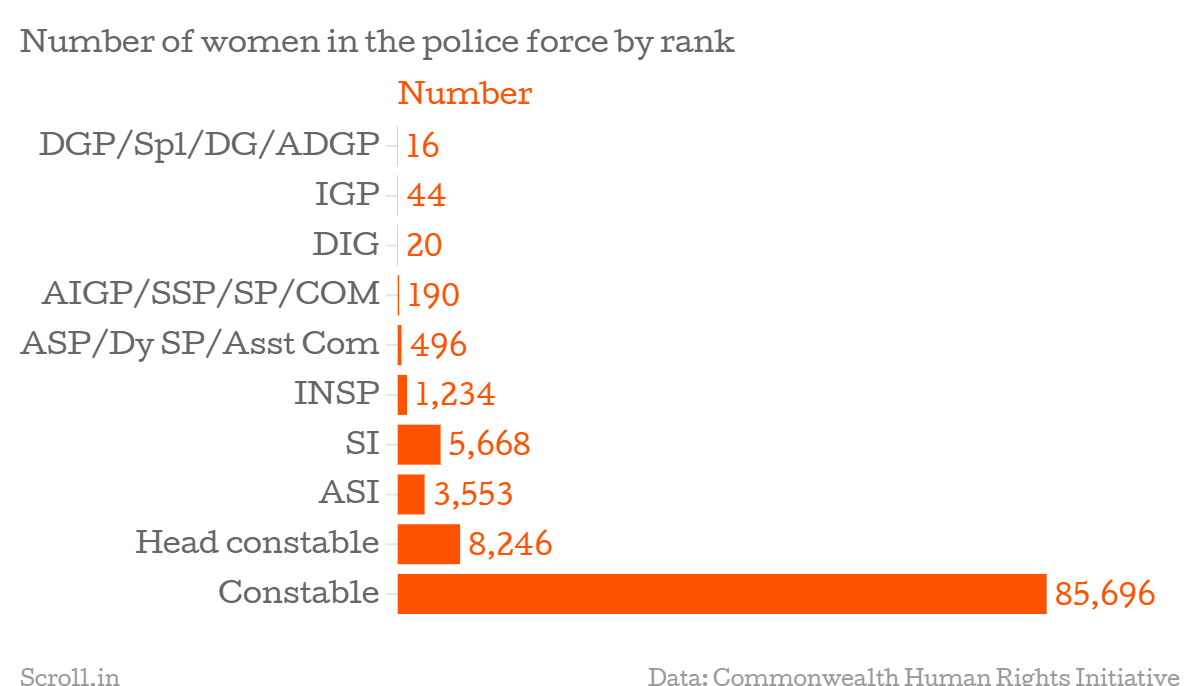

At first glance, the numbers of women by rank look promising.

But when seen as a percentage of the total, this image fades.

The gaps begins at the time of recruitment. Several states have separate cadres for recruiting men and women, leading to an imbalance in numbers, though this is slowly changing.

Andhra Pradesh, for instance, took a step towards erasing gender differentiation, when it made recruitment and promotion independent of gender. In 2012, Meghalaya instituted a Transparent Recruitment Process in which candidates do not have to reveal their names – or genders – in a computerised test and are judged solely on the answers entered.

A senior officer in Meghalaya said this had encouraged the number of women applying. The officer said that in the last round of recruitment for sub-inspectors, 40 people of a batch of 100 were women.

In Rajasthan, the report noted that districts with higher levels of literacy saw more women applying to join the police, even as the overall recruitment of women remains low, at 7.11% of the total force.

Kerala on the other hand lags behind, the report points out. Until 2014, the state did not permit women to directly apply for the rank of sub-inspector. Even now, it does not have recruitments at the same rank for women or the physically handicapped.

That said, there has been an overall relatively steady increase in women in the workforce over the years.

Even this might be too slow, according to a report by Bureau of Police Research and Development cited by the study. Working hours can come down only with increased recruitment – of exactly 337,500 police personnel.

These, the report suggested in a radical policy shift, should be only women, adding that “This step would, thus, serve twin purposes of introduction of shift system in police stations as well as enhancing women’s presence in the police for better policing.”

As for the report, it recommends against gender-segregated cadres, pointing out that it limits entry-level positions for women and restricts their promotions, while also inhibiting “considerations of merit between the genders”.

Work culture

Outside the force, women hesitate to report cases of sexual harassment to male police officials, sometimes because of their attitude. This seems to apply even to women inside the force. Senior leaders tend to not want to acknowledge or share information about the problem, the report says, even though women in group discussions and face to face interactions spoke out about it.

“Who can one complain to?” one woman police official asked. “Women feel reluctant to complain because they feel that the senior will take it out in another way – the woman will build image of a complainer."

In Kerala and Haryana, nearly 30% of women did not even know they could complain about harassment, even as over 90% said they had not faced any such issues. And even those who complained had no guarantee that action would be taken, even if internal inquiries confirmed the truth behind allegations.

Women also spoke out against a wider theme of discrimination in the work culture of the force.

Women are assigned to very narrow tasks, such as cases related to women and children, escorting female prisoners and assisting “men police” in their duties. They are also given desk jobs, as data entry operators and record keepers.

Another pointed out how leave is viewed differently.

“There is a mentality of discrimination…there is a lot of talk about women not working but there are so many male constables in line of duty who are useless, lying drunk, no one has an issue about that,” the interviewee said. “But if a woman asks for leave then everyone has a problem.”

Over time, women seem to internalise these discriminatory attitudes. The report quotes a study by M Natarajan in the International Journal of Police Science and Management, which points out how attitudes of women changed in Tamil Nadu, where both men and women police officers agreed that men are more effective at their jobs.

Access to amenities

Police stations, notorious for their lack of amenities, often do not have toilets. As an extension of that, there are very rarely separate toilet facilities for women. This leads to very specific problems.

“A female traffic constable in Rajasthan stated categorically that the toughest part of her job was unavailability of toilet facilities,” the report said. The discrimination is also hierarchical. Rajasthan, for instance, built toilets for women in its new headquarters. These are only for Indian Police Service officers, not for state cadres.

As for what women want, they were clear, the report said. “When asked what three things would make their work more comfortable, fixed shift work was a common refrain and there was almost unanimous agreement on the need for flexible working hours for all police officers.”

One respondent said, “In every thana one woman police has to be there for crimes against women. We do not have enough police officers to decrease the workload.”