On Earth, though, baobabs are quite the opposite. Anyone living in Africa where baobabs grow to enormous sizes would be able to tell you about the numerous benefits the trees provide for humans and animals.

They would probably describe the marvellous generosity of its trunk and its hospitality to many creatures, and extol the hardy and light fruit pod with its deliciously powdery pulp and nutritious seeds that remain fresh and edible over long periods of time.

The baobabs on Asteroid B612 From www.lepetitprince.com

But there is a mystery to baobabs, as they are also found in India. How did they get there? Our new research is starting to shed light on the answer.

Where baobabs are found

African baobabs (Adansonia digitata) are one of nine species of the genusAdansonia. The recently identified A. kilima, which occurs in the highlands of eastern and southern Africa, is very close to A. digitata and is sometimes considered within this broad species.

Outside mainland Africa, there are six baobab species belonging to Madagascar, and one species in the Kimberley region of northwest Australia (known as the boab). The African baobab, though, is most widely distributed both in its home continent and in the neo-tropics where enslaved Africans were brought to work.

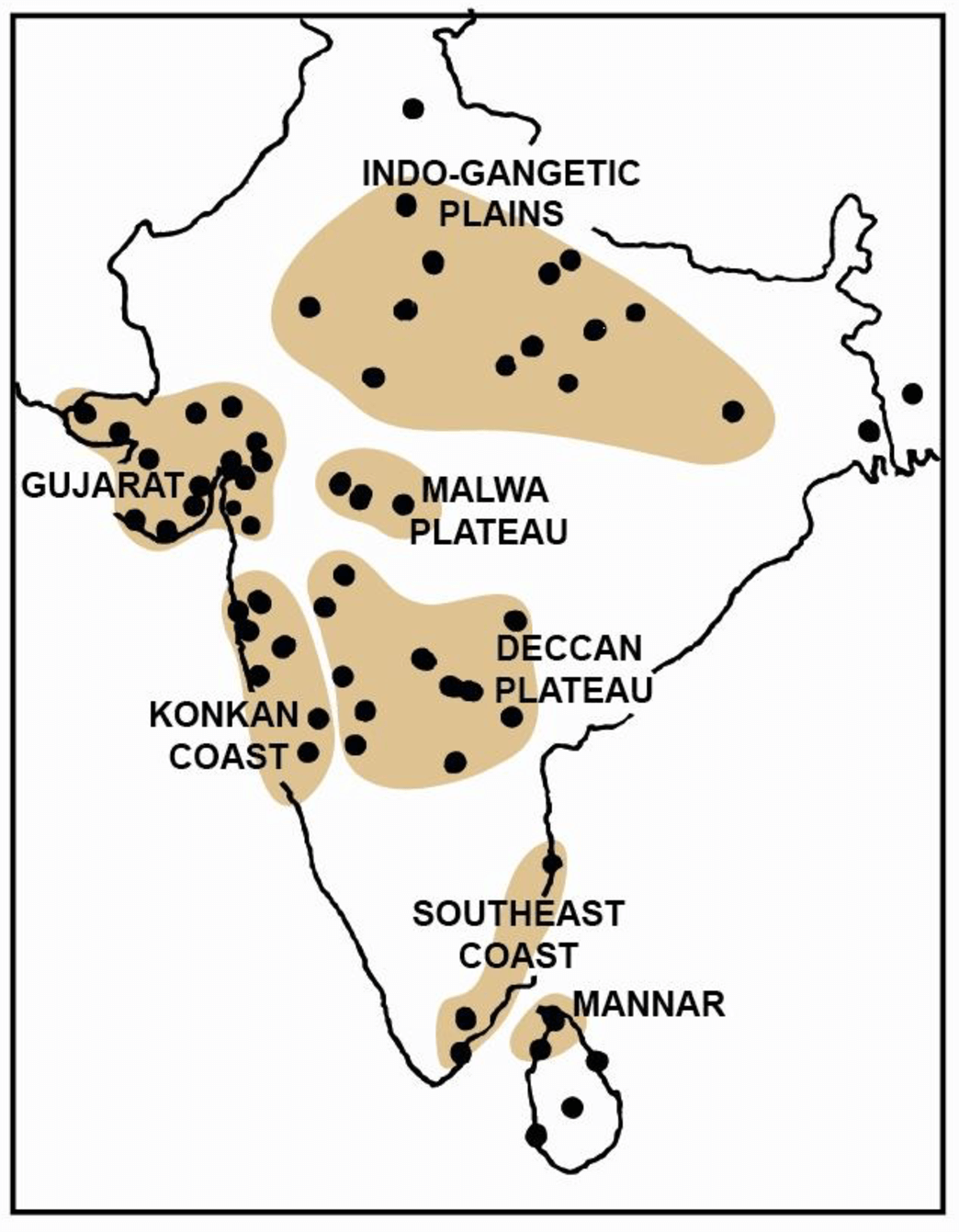

Baobabs are found in different parts of the Indian subcontinent, and many of them are so voluminous that they could easily be several thousand years old. No one knows how they arrived in these places. A few studies on baobabs in India have speculated that the fruit pods may have floated across from Africa on ocean currents and washed up on the shores, or that they may have been brought over by Arab traders.

How did they get to India?

In a recently published study, we investigated how African baobabs were introduced to the Indian subcontinent by combining genetic analysis of baobab trees from Africa, India, the Mascarenes and Malaysia with historical information about different periods of Indian Ocean trade.

Baobab distribution in South Asia Rangan and Bell 2015

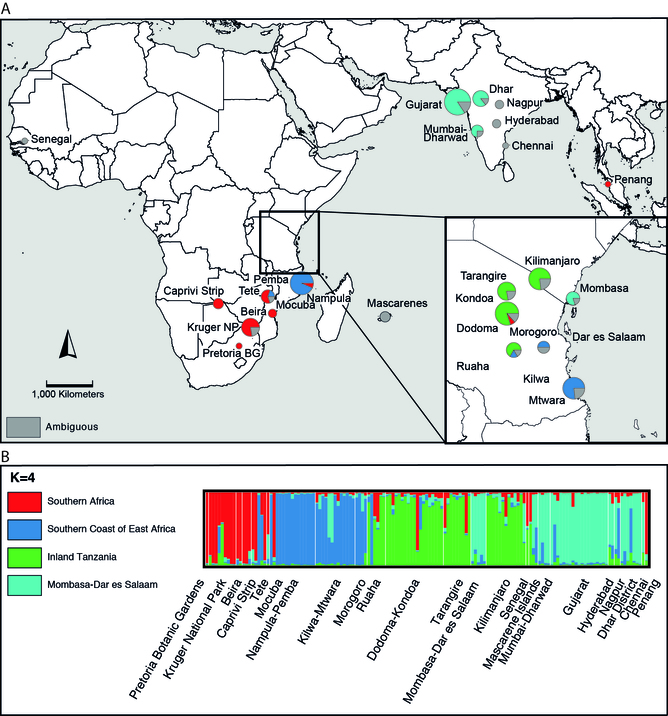

We looked at the genetic material to identify the population source regions in Africa and see how these were represented in the baobabs in India, the Mascarenes and Malaysia. We then compared the regional relationships revealed by the genetic analysis with historical accounts of trade and interactions between Africa and these places to infer the pathways of dispersal.

The genetic analysis produced very interesting results. First of all, it showed that the Indian baobabs were the same species as the African species Adansonia digitata, and that there was less genetic diversity in the Indian baobab populations compared to the African populations. This confirmed our hunch that the baobabs had not been in the Indian subcontinent long enough for the populations to diversify, and that their dispersal by ocean currents was less likely than introduction by humans.

However, it also showed some of the Indian baobabs had private alleles that were not present in the African populations. This implied that they could have been from other African baobab populations and brought by humans to the subcontinent much earlier than assumed.

Our second discovery was that there were multiple introductions of baobabs to the Indian subcontinent, and that these were not from just one, but several biogeographic regions of Africa.

Although many of the Indian baobabs showed close relationship with populations from coastal areas of Kenya and Tanzania, there were some that showed closer relationships with baobabs from coastal and inland Mozambique, and also, surprisingly, from West Africa.

The third revelation was that baobabs populations in particular places in inland Mozambique and coastal Tanzania belonged to different genetic clusters which meant that they had been brought to these places from elsewhere.

Map showing the regional genetic clusters of African baobabs and their proportions in individual samples Bell, Rangan et al. 2015

Tracing connections and pathways

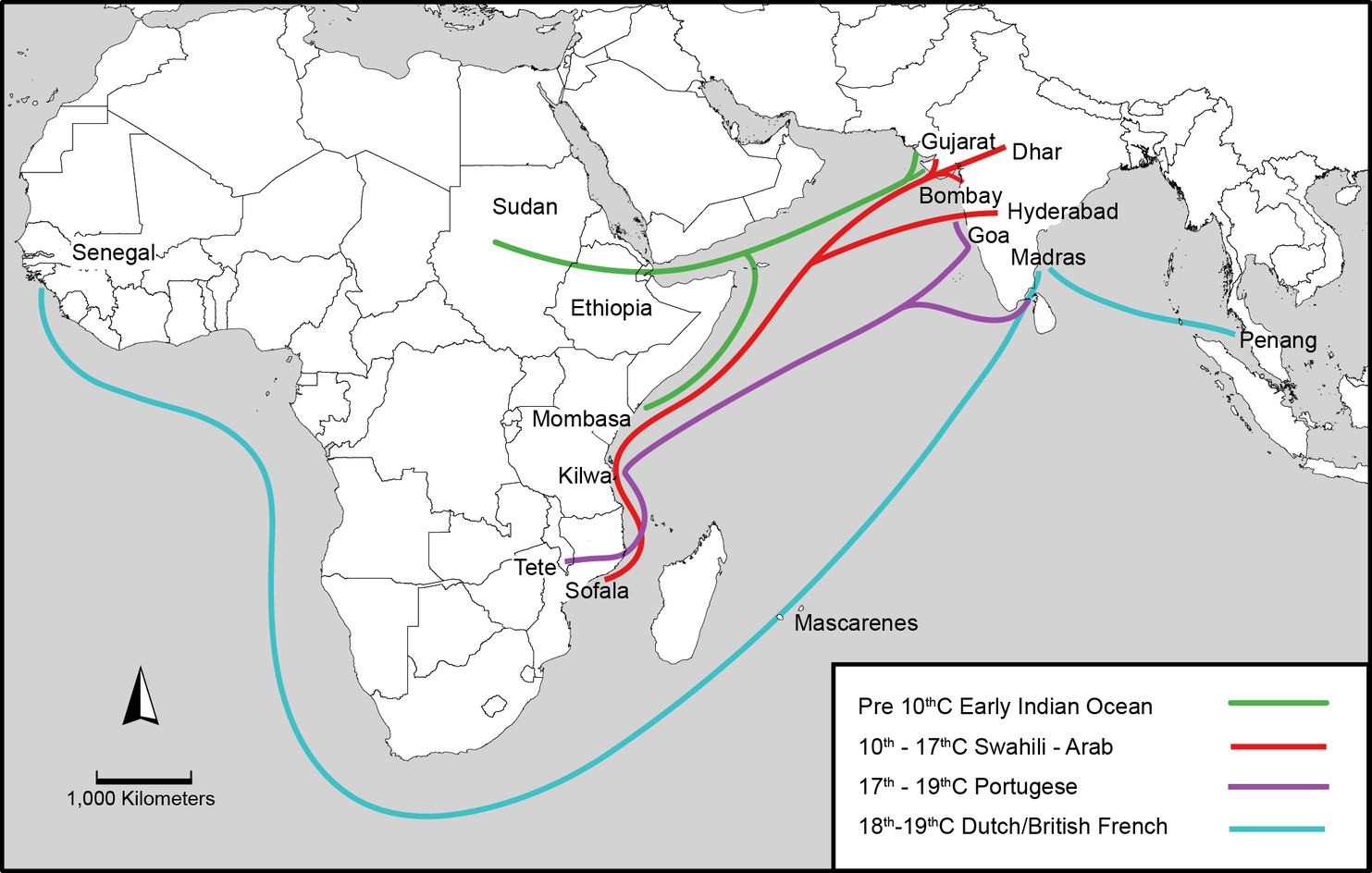

When we combined these findings with archaeological and historical accounts of Indian Ocean trade, we identified four major periods during which Africans from different regions of that continent would have travelled to the Indian subcontinent and beyond to Southeast Asia.

The earliest interactions go back more than 4,000 years ago, when African cereal and legume crops arrived in India from Sudan, Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa.

The subsequent expansion of the Indian Ocean trade between Africa and India occurred through Swahili-Arab networks. The arrival of the Portuguese and the establishment of their colonial bases in Mozambique and western and southern India contributed to new flows of Africans between these places.

And finally, we found that during the 18th and 19th centuries, the English and Dutch colonial authorities recruited soldiers from West Africa for regiments in southern India and Southeast Asia.

Inferred pathways of introduction from Africa to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia Bell, Rangan et al. 2015

In addition to this combined genetic-historical analysis, we found that the cultural practices and beliefs associated with baobabs in particular places in India showed striking similarity with those from specific regions of eastern and southern Africa.

This led us to the marvellous realisation that the geographical distribution of baobabs in the Indian subcontinent are living reminders of the long history of African diaspora across the Indian Ocean.

We hope that when The Little Prince comes back for a visit from asteroid B612, we’ll be there to assure him that baobabs are the most wonderful trees on Earth and, if you sit by their side and listen carefully, they’ll tell you stories of people who have been forgotten in history books.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.