“Who has made this list?” asked Vinay Kant Mishra, who works as a machine operator. “Please tell me which vegetable costs Rs 16 per kilo and where can one can stay for Rs 390 per month?”

Mishra’s mirth is not shared by central trade unions. The unions are filled with misgivings as the National Democratic Alliance government prepares to restructure labour laws through eight legislative amendments in the winter session of the Parliament in November. Troubling them the most is a proposed amendment to the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, that will set a legally binding national minimum wage – below which no worker can be paid – across all Indian states and industries.

The problem, they say, is that the Indian government is not raising it enough.

In its draft calculations, the government has set the national minimum wage at Rs 273 a day or Rs 7,100 a month, say trade unions. This is less than half of what it ought to be if the Supreme Court guidelines, and the norms proposed in the Indian Labour Conference 1957, were applied to current prices. The unions demand that every worker be assured of at least Rs 15,000 a month in wages.

What will change?

At present, the central government and the states fix the minimum wage in different categories of work. Under the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, the Centre determines the minimum wage in 45 categories and the states in 1,679 categories. Labour economists say multiple deciding authorities and wage rates make it difficult for workers to know, and demand, their minimum wage, which worsens income inequality and poverty.

It doesn’t help that though there is a national floor minimum wage does exist – currently fixed at Rs 160 a day – it is only suggestive and not legally binding. This means that the authorities can set the daily minimum wage lower than Rs 160, if they so deem.

The government says the amendment to the Minimum Wages Act, 1948 will address some of these issues. It contends that a legally binding national minimum will lead to better compliance – in 2010, only 61% workers in India got paid a minimum wage. Union Labour and Employment Minister Bandaru Dattatreya describes the proposal on wages as a sign of the government’s “positive approach to workers’ demands”.

PP Mitra, Principal Labour and Employment Advisor, Ministry of Labour and Employment, says the government recommended the new minimum wage after tripartite talks with industry and trade unions, and after it was cleared by an Inter-Ministerial Group headed by Finance Minister Arun Jaitley.

“A national minimum wage has been proposed in the Bill after wide consultations with industry and trade unions,” Mitra said. “We have divided states and union territories into three categories – high-, middle- and low-income. The tripartite Central Advisory Board on minimum wages will further recommend wages in each category.”

Whatever the Board’s final suggestions, a national minimum wage of Rs 7,100 will still be lower than the existing minimum wage for unskilled work in some states, such as Haryana (currently Rs 7,600 per month) and Delhi (Rs 9,178 per month). It will only help workers in states such as Uttar Pradesh, where the minimum wage is currently fixed at Rs 6,814 per month.

Trade union representatives have opposed the government proposal. They say the government is undermining tripartite institutions. “The Central Advisory Board on wages has not met even once since this government came to power,” noted Dr Kashmir Singh, a member of the Board and General Secretary, Centre for Indian Trade Unions. “How do they then expect the Board to play a more active role in recommending revisions under the new law?”

Calories and other calculations

Ministry officials say the government arrived at the new national minimum wage by following the recommendations of the 15th Indian Labour Conference (an annual event organised by the ministry of labour and employment to decide on workers’ issues) of 1957, and the Supreme Court in the Raptakos Brett Vs Workers’ Union case of 1992.

The 15th Indian Labour Conference had recommended fixing minimum wages based on:

1. Per capita food intake of at least 2,700 calories for a worker’s family of three members

2. Per capita cloth of at least 18 yards per year

3. House rent at the rate of 10% of the expenditure on food and clothing

4. Fuel/lighting, etc. at the rate of 20% of expenditure on food and clothing

Decades later, the Supreme Court ordered that 25% of the expenditure on food, cloth, rent, fuel should be added as expenses on education, health, etc. to calculate the minimum wage.

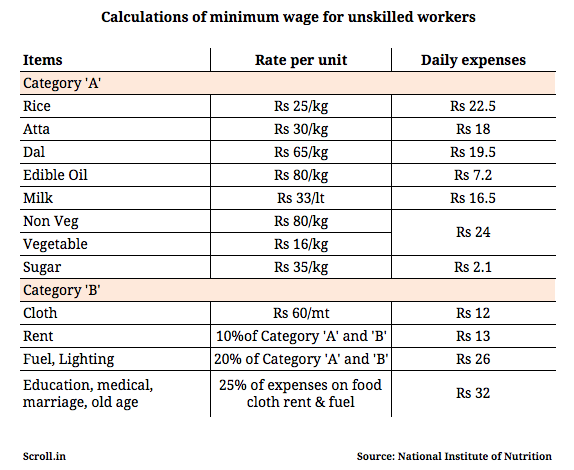

Using this formula, the National Institute of Nutrition in Hyderabad estimated that the expenditure of a worker in the smallest class ‘C’ cities adds up to Rs 211 daily or Rs 6,330 per month. After inflating this with the consumer price index for June, the figure was rounded off to Rs 7,100 per month. Government experts arrived at this calculation by estimating everyday expenses at the following rates:

As the table shows, the proposal is based on calculations which estimate dal at only Rs 65 per kilo, vegetable at Rs 16 per kilo, milk at Rs 33 a litre, and a monthly rent of Rs 390. These rates are patently out-dated, point out trade unions.

“In 2014, we prepared an estimate on basis of actual average of retail prices of these items in seven cities – Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata Bangalore, Bhubaneswar and Thiruvananthapuram,” said Tapan Sen, Rajya Sabha MP and vice president of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions. “The expenses come to Rs 20,861 [a month], or Rs 802 a day.”

Gurudas Dasgupta, who is General Secretary of All India Trade Union Congress, says that 12 central trade unions have proposed pegging the national minimum wage at least at Rs 15,000 a month.

Workers in Uttar Pradesh and Haryana express amusement at the government’s estimations.

“Tur dal is now Rs 200 per kilo, milk is Rs 55 a litre,” said Rajesh Yadav, who works with Vinay Kant Mishra at the forging unit of Bajaj Motors in Bawal. Yadav pays Rs 3,000 for a one-room tenement in Bawal and an electricity bill of Rs 1,000 per month. He says his wife and children lived in the village near Kanpur because he could not afford space in Bawal for all of them.

Ram Vachan, a welder at a metal polish unit in sector 80 in Noida, Uttar Pradesh, says he finds it difficult to support a family on a salary of Rs 7,000 per month because of the steep living costs in Noida. “For some years now, along with wages, the company has given us monthly rations,” he said. “They gave us 5 kilo atta, 3 kilo rice, and 2 kilo chana dal every month. But three month back chana dal rates doubled from Rs 40 to Rs 80, and they cut chana dal rations by half, from 2 to 1 kg a month.”

Brijesh Upadhaya, who is General Secretary of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh-affiliated Bhartiya Mazdoor Sangh, says it was a positive development that the government is willing to set a legal national minimum wage. “The government is willing to follow the guidelines,” declared Upadhaya. “The rates can be updated and revised later on.”

For their part, representatives of the Confederation of Indian Industry, an association of Indian businesses, say it will be best to leave the fixing of minimum wage to state governments, who may “fix this as per local conditions and economic dynamics”.

*Workers' names have been changed