Last week, The Hindu reported that the government had directed the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research to generate half of its funds. Girish Sahni, who took over as Council director general two months ago, strongly refuted this while speaking to Scroll.

“There is a general feeling that we should raise external funding because financial autonomy will also make us functionally autonomous,” said Sahni about a meeting of heads of Council laboratories with the Minister for Science and Technology Dr Harsh Vardhan.

The meeting was a "Chintan Shivir" (brainstorming camp) and the outcome was a document called the Dehradun Declaration, a commitment to recast the Council laboratories to make them entrepreneurial and more socially relevant.

But the Council had not received any notice from the ministry that government funding to it is going to be cut, Sahni said. “It was generally felt and endorsed also that CSIR would try to become self-sustaining over a period of time. There were no numbers crunched whether this would be 20%, 30% or 50%.”

The Council has been quick to start working on the goals of the Dehradun Declaration. Research heads in its laboratories have been asked to fill out a 12-point proforma to set milestones for the current financial year for funding from the government, sponsored projects, and services and royalty. They also have to indicate how they will develop technologies in service of schemes like Swachch Bharat, Make in India, Smart Cities, Namami Ganga and so on. The laboratories also had to state in the proforma how they will become catalytic agents to transform India into Samarth Bharat-Sashakt Bharat – competent and strong India.

Moreover, scientists have to declare how they will achieve global standards, develop 12 game-changing technologies every year, cater to the aspiration of the common man, and establish their social relevance.

Scientists agree that the mandate of the Council has always been research that will deliver to social and industrial needs. But many believe that the council does not have the foundation to make the grand transformation stated in the Declaration.

'A political statement'

“The CSIR directors themselves seem to have signed up to a political statement. That in itself is a bit of a tragedy,” said Rajeshwari Raina, scientist at the National Institute of Science Technology and Development Studies, which is a Council laboratory. “If you want science to cater to those development ends, like having 12 transformative technologies, that would mean that the ecosystem for those transformative technologies is already there and we are just waiting for the technologies. Now we know that that’s not the case in India.”

For the Council to deliver to industry, it must first develop linkages with other domains of innovation like rural infrastructure, banking services and production, according to Raina. “The councils are all known to some extent for being very bureaucratic and rigid. The kind of linkages that you need to make in the industrial innovation system is really not allowed in CSIR labs,” she said.

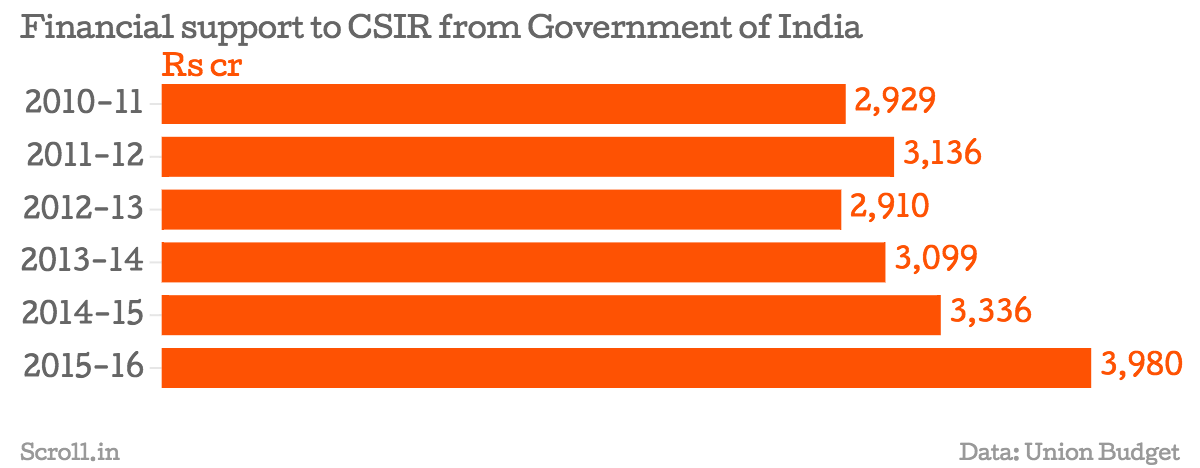

The other big question mark is over how the Council facilities will become self-sufficient in two to three years. Sahni estimates that the current amount of external funding to the Council is between 25% and 30% of its total expenditure.

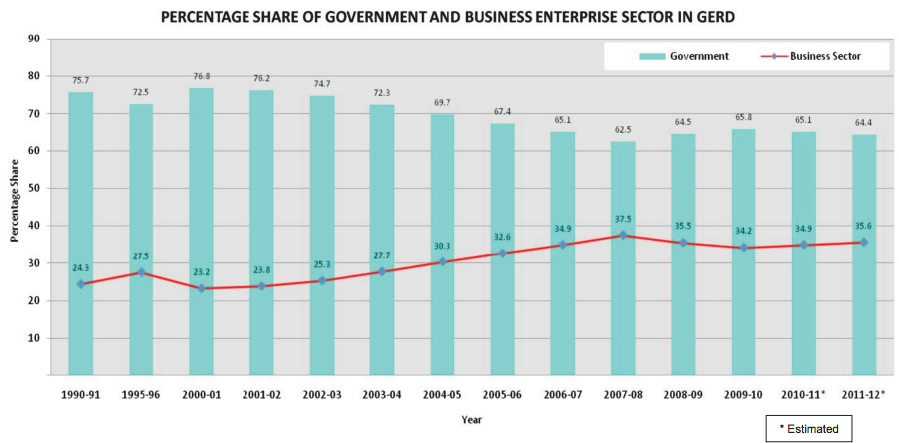

Gangan Prathap, retired senior scientist at the National Institute of Interdisciplinary Science and Technology, said a laboratory becoming self-sufficient is close to impossible unless the private sector seriously ramps up its contribution.

The current gross expenditure on research and development, often abbreviated as GERD, has tripled from Rs 24,000 crore to Rs 75,000 crore since 2005. Private sector contribution to this corpus has been slowly growing over that period.

Source: Department of Science and Technology.

But that growth is not fast enough. “One problem is that the private-sector (mainly industrial but now also including the service/Information Technology sector) is not doing or funding the research it should be doing. If the government spends Rs 75,000 crore a year, they should be spending 4 times as much.” Prathap wrote in an email to Scroll.

Expecting the Council laboratories to generate more of their own budget is not new. Roddam Narasimha, professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research and former director of the Council's National Aerospace Laboratories, recalls that in the 1990s the Council decided to try to raise 30% of its budget from industrial contracts. “That was just a norm. Some laboratories did better than 30%, some laboratories didn’t do so well. So the concept that CSIR should bring in part of its money is decades old. However, there seems to be a little greater inclination on the part of the government that this should be enforced,” said Narasimha.

Unequal funding?

A problem that arises from depending more on the private sector for money is the prospect of unequal funding to the many different kinds of the Council laboratories depending on industry priorities. “India’s two sectors that are doing well are chemicals and pharmaceuticals and high-end production sectors like cars, two-wheelers and fridges. Those sectors may be raising money but how about a lab that does pottery and agro-processing? How about a lab like us that does social studies for science?” asked Raina.

The new Council initiative comes at a time when funding for science and technology in general in India is under a cloud. India's share of global research funding has remained static at 2.7%. The country's budgetary allocation to science and technology has consistently been below 1% of gross domestic product even as we try to compete with South Korea, a country that invests 4% of its GDP in scientific research.

In the last two years of the United Progressive Alliance government, the money just was not available due to fiscal constraints, scientists were told. Now they feel there is little inclination to finance science. “At least for the last two years, funds have been promised but they haven’t come and new activities are not forthcoming,” said Satyajit Mayor, director of the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bengaluru, which is affiliated to the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research and not a Council laboratory.

“We need to send out a strong message that whatever is being created will be destroyed if funding doesn’t flow. If you are not going to be supporting basic, fundamental science then I don’t see how we can do anything that is connected to building up capabilities to do any translation in this country,” said Mayor.

Amidst the scepticism of his colleagues, Sahni maintains that the move towards self-sufficiency is good. “This is probably the healthiest thing for everyone concerned but there has to be a consensus around it,” he said. “There is a gross over-reaction to some of these things, which are basically well-intentioned. This is an unpolitical, honest assessment.”