Children aren’t getting their hot meals regularly, nor are grassroots workers receiving their wages on time. To compensate for this, villages in at least one part of Punjab are being asked to provide grains and sugar so that vulnerable children can get the nutrition they require.

Funds and rations delayed

The Integrated Child Development Scheme is the largest universal programme for children, serving 8 crore children below the age of six years. It provides take-home dry rations at village-level anganwadis (crèches) to children younger than 3 years and to pregnant and lactating women. Children in the age group of 3-6 years get hot meals under the scheme, which additionally focuses on immunisation, health check-ups, growth monitoring, pre-school education and health education programmes for adolescents.

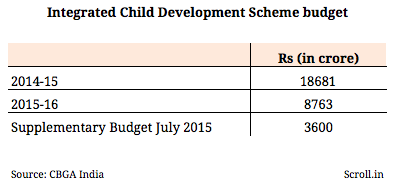

In February, the National Democratic Alliance government halved the funds for the crucial scheme in the union budget, from Rs 18,681 crore to Rs 8,335 crore for 2015-’16.

A few months on, anganwadi workers from Uttar Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana say there have been delays in the supply of funds to buy dry rations and consequent disruptions in hot meals for children.

“We get Rs 3,100 per month to prepare one hot cooked meal a day for every 40 children aged between 3-6 years,” said Rajeshwari Devi, an anganwadi worker from Bulandshahar in Uttar Pradesh. “Since July, funds are not reaching us regularly. We did not get money some months, then got it for several months in one go. Several other anganwadi centres haven’t got funds for the last couple of months.”

Geeta Sharma, who has worked as an anganwadi sewika in Arniya in Uttar Pradesh since 1995, said there were instances in the past too when anganwadi workers’ wages were not paid on time, but never was it this bad. “Also, this is the first time even our block supervisors have not been paid since two months," she said. "When we go to them and enquire, they throw up their hands and ask what can they do.”

Rajeshwari Devi and Geeta Sharma were among more than 500 anganwadi workers from 10 states who came to Delhi in early November to attend a meeting of the All India Federation of Anganwadi Workers and Helpers and protest against the shrinking of social policies.

At the meeting, anganwadi workers from Punjab said they had been constrained to ask village communities to donate grains and sugar so they could continue providing nutritional supplements and snacks to children at government anganwadis.

“Since last few months, we are not getting rations regularly,” said Gurcharan Kaur, an anganwadi worker in Moga in Punjab. “Some months there is no sugar, and at other times cooking oil is missing. Twice this year, I have had to ask people in my village to donate sugar so we can keep the anganwadi running.”

Veena Dhimwal, from Yamunanagar in Haryana, said the fund cuts were undermining the role of anganwadi workers in the poorest areas. “The rich and middle class households don’t listen to us,” said Dhimwal. "But in villages with backward castes and Dalits, a lot of families send their children to anganwadis for meals. After fund cuts, anganwadis in the poorest districts will not get any new infrastructure or improvements.”

The General Secretary of the All India Federation of Anganwadi Workers and Helpers, AR Sindhu, said the unions under the umbrella organisation are planning a protest march to the Parliament. “Anganwadi employees are not being paid wages in Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra since the last four-five months,” said Sindhu. “The Ministry of Women and Child Development has failed to address these concerns.”

Basic responsibilities

The Integrated Child Development Scheme was launched as a central government scheme in 1975 and since 2010 has been by the Centre and states on a cost-sharing basis. There are three type of costs – salaries and administrative expenses, the cost of rations, and finally creating new infrastructure and building new anganwadis.

Till 2014, the Centre and states equally shared the cost of grains and foodstuff, while the administrative and other expenses were divided in the ratio of 90:10, with the Centre shouldering the bigger share.

When the Finance Ministry announced the budget cuts in February, reducing this scheme’s budget by Rs 10,346 crore, it said that states will have to bear most of the expenses. From 10% earlier, the entire cost of the wages of anganwadi workers and other staff was transferred to the states. In addition, the states were asked to take on the cost of dry rations and food grains.

These were significant changes and required the states to redraw their budgets in a month’s time by March 31. One month was too little for this overhaul, explained Nilachal Acharya, a senior researcher with the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability, a public policy centre in New Delhi.

“After the presentation of the Union budget in February this year, states were given little time to reformulate their annual budgets,” said Acharya. “Several states asked for funds for the Integrated Child Development Scheme even while presenting their budgets after March 15 because by then, they had already allotted funds for priorities in the states, as per their chief minister’s election promises, etc.”

The Integrated Child Development Scheme had not been a big focus of states expenditure so far, Acharya explained, “and unfortunately, most states have not yet shifted resources from other general expenses to social schemes”.

Minister for Women and Child Development Maneka Gandhi had protested against the budget cuts to the Integrated Child Development Scheme, questioning how salaries will be paid and new anganwadis created. Sometime later, the Finance Ministry allotted an additional Rs 3,600 crore to the scheme in the supplementary budget. But even after this, its budget was 34% less than last year’s.

Budgetary allocation to ICDS

Moreover, seven months into the new fiscal year, state governments still don’t know what will be the share of Centre and states in funding legislatively-backed social schemes such as the Integrated Child Development Scheme. A Niti Aayog panel on Centre-states sharing of funds under Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan was set up in March and its recommendations were made public only this month.

Dipa Sinha, a Right to Food campaigner, spoke of how the new way of cutting funding had disrupted the scheme’s functioning. “The government should have first let the panel submit its recommendations after consulting states,” she said. “Now, neither central nor state funds are reaching and the scheme is in disarray. The worst affected are the children.”