Kher, whose wife is a Bharatiya Janata Partty member of Parliament, is only the latest, in a long line that includes government ministers, members of Parliament and party acolytes, to suggest that the prime minister who leads a government with a firm parliamentary majority, is being victimised and needs to be defended against democratic dissent.

As Prime Minister-elect, making his victory speech in Vadodara on 15 May 2014, Narendra Modi had declared: "I want to tell my fellow Indians that in letter and spirit I will take all Indians with me. This is our aim, and I will not leave any stone unturned."

Modi’s fine words however failed to restrain the vituperation of his party's members of Parliament, legislative assemblies and other activists. Delhi voters were told they had to choose between the “Ramzaade" (sons of Ram) and "Haraamzade" (bastards). There was a growing sense of disquiet created by the continuing campaigns of the party's political network – like “gharwapsi” or the “re-conversion” of Muslims.

But the prime minister was silent through it all. He clearly believes that the damage is done by media coverage of a problem but not by the problem itself.

The sense that there was something just not right with his silence came through strongly when President Obama, as feted Republic Day guest of honour, spoke to an Indian audience in New Delhi about the need to defend India’s constitutionally guaranteed plurality and right to freedom of conscience.

A few weeks later the prime minister, quoting the United Nations' Universal Declaration of Human Rights, made a commitment to these values:

“…My government will ensure that there is complete freedom of faith.... My government will not allow any religious group… to incite hatred against others, overtly or covertly. Mine will be a government that gives equal respect to all religions. India is the land of Buddha and Gandhi. Equal respect for all religions must be in the DNA of every Indian. We cannot accept violence against any religion on any pretext and I strongly condemn such violence. My government will act strongly in this regard.”

Fighting words. But like his Vadodara victory speech they rang hollow.

Deafening silence

When a man, the father of an Indian Air Force airman, was killed inside his home in Dadri, Uttar Pradesh, by a lynch mob, which claimed its sentiments were hurt by a rumour that he had eaten beef, the prime minister remained silent. His cabinet colleagues and other BJP elected representatives justified the lynching amidst growing concern over other murders in the name of cows and Hindu sentiment in different parts of the country.

The prime minister had, in his first Independence Day address called for a “10-year moratorium” on sectarian violence, saying, “You will see that how much strength we get from peace, unity, goodwill and brotherhood. Let`s experiment it for once.” Yet, instead of a strong statement to reinforce this message and his endorsement of the Universal Human Rights Declaration, mealy mouthed ministers argued on his behalf that these, clearly communal murders, were a “law and order” problem, that had occurred in non-BJP governed states and that law and order was a state subject. The academics and artistes who, with Anupam Kher, signed the statement criticising the critics, have simply repeated this argument now.

A few weeks earlier, when he set out to campaign in Bihar, Modi was voluble about the insult to the traditionally cow-herding Yadav caste and to “all Indians” caused by Lalu Prasad Yadav’s statement that “even Hindus eat beef”. In speech after speech in Nawada, Begusarai and Munger he repeated these words, describing himself as a man who had come from the land of Lord Krishna’s birth and so had kinship with the Yadavs who were so insulted.

It was the President of India, Pranab Mukherjee, who finally called for an adherence to civilisational values of diversity, plurality and tolerance. It was only then the prime minister spoke. In what seemed like a fit of pique, he reminded people that despite bomb explosions at the venue of his Lok Sabha election rally in Patna, he had “ensured no reprisals” and called on Hindus and Muslims to work together to fight poverty. He then told people to pay heed to the President's words, but he did not say what words the President had used.

This was described by the media, which was willing the prime minister to condemn the attacks, as Modi finally breaking his silence on the communally motivated lynching in Dadri. But, the fact is, Modi’s exhortations were part of a campaign speech and were prefaced by his claim that Yadavs, Biharis and all Indians, were insulted by statements that Hindus eat beef. In subsequent speeches in other towns he did not repeat his call for Hindus and Muslims to work together or to heed the presidents words, but repeated ad nauseam his lines about the insult caused by beef, lending weight to those looking for justifications for attacks based on rumours about beef eaters and cattle rustler.

As the campaign progressed the prime minister also wagered his life to defend existing reservation quotas for Dalits, Mahadalits and backward caste Hindus against what he called a conspiracy by the Janata Dal (United) coalition to steal or grab 5% of the reservation quota, and give it to “another community based on religion” . This was a less than honest interpretation of a proposal to bring these deprived minority community members within the purview of affirmative action, and unambiguously aimed at claiming sole leadership of Hindus. It was a far cry from the man who said in letter and spirit I will take all Indians with me”.

'Go to Pakistan'

The BJP appears to have its own definition of Indian. The Culture Minister, Mahesh Sharma, gave some indication of the parameters of this Indian-ness when he said that “despite being a Muslim” the late former President APJ Abdul Kalam was a patriot. His statement revealed the prejudice of a swayamsewak who, like the prime minister, learnt his politics in an RSS shakha.

When the issue of communalism came up for debate in Parliament this summer, the avowedly anti-minority member of Parliament for Gorakhpur, Yogi Adityanath, was picked to respond to the motion from the government benches. In the course of his speech, Adityanath, said: “Hindu is not a community but the epitome of nationality”, and announced, to approving table-thumping by BJP members of Parliament ranged behind him and with the home minister present in the house, that the parliamentary opposition protected terrorists and was “working to Pakistan’s agenda”.

During the Lok Sabha election campaign, Giriraj Singh, who is now in Modi’s cabinet, had said all those who opposed Modi had no place in India, and should go to Pakistan. The BJP election posters in Bihar have echoed Adityanath and Giriraj Singh. As has the BJP party president Amit Shah, who said in election speeches that Bihar under the JDU had become “a haven for terror modules” and that Pakistan would celebrate a BJP defeat in Bihar.

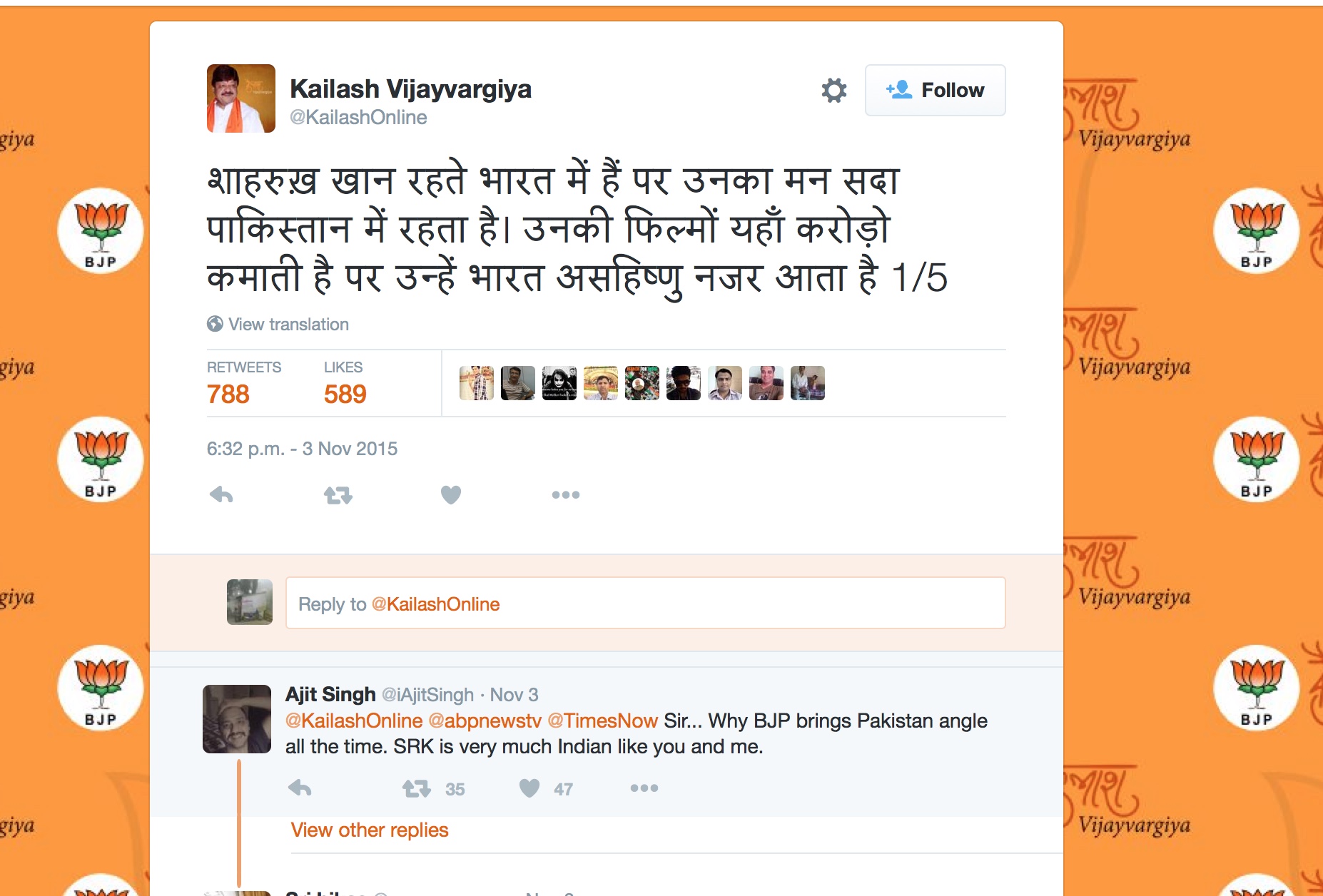

The BJP General Secretary Kailash Vijayvargiya reacted to the actor Shahrukh Khan’s statement that there was extreme intolerance in India by confirming the fact. “Shahrukh lives in India, but his soul is in Pakistan,” he tweeted.

Adityanath bettered him, saying “there is no difference between the language of Shahrukh Khan and Hafiz Saeed”, the Pakistani terrorist leader said to be responsible for the terror attacks in Mumbai in 2006 and 2008.

Their unmistakable message is that those not with the BJP or critical of it or its leader are fifth columnists acting on behalf of the enemy. The opponents of the BJP are enemies of India and hence, in the BJP’s book, they are Pakistani. So far there has been a tendency to call those who make such statements the “fringe”. But, if the BJP party president, a party general secretary, a five-term MP and a cabinet minister are the fringe, what is the mainstream of this party? Is it the group of Delhi based ministers, party members and party acolytes who have excoriated the writers, artists, scientists and filmmakers who have protested the murders of writers and ordinary Indians in the name of community sentiment? This group, has also created a simple dichotomy – with the BJP and against the BJP, for Modi and against Modi, labelling all concerned citizens and critics of the government as stooges of the Congress or Communists or confirmed Modi haters.

Missing in action

Modi, instead of showing leadership when it has been demanded of him, has chosen to hide behind such petty arguments. At other times he has not shied from confirming his critics' worst fears, as with his partisan election rhetoric in Bihar.

In his Vadodra speech, Modi had said, "The election period is over and it is time to put the heat and dust behind," and "I hope I will get the support of everyone, including my opponents." Modi appeared to suggest that the sharp, divisive and accusatory electoral rhetoric was part of the rough and tumble of an election campaign and should not impact the work of governing the country. To make this possible the party in government would have to have a leader who can “in letter and spirit take all Indians” along. Modi is not that leader. He wants people to follow, but he does not know how to lead.