“Jal-Janmat is a clear message to all the political parties that if they want our votes, they need to address the issue of contaminated drinking water,” said Rajendra Jha, secretary of Kosi Seva Sadan in Bihar’s Saharsa district.

Contaminated drinking water is, indeed, a cause of grave concern in Bihar, even if it didn’t feature prominently in the election speeches of the many contenders in the race. In large parts of the state, the groundwater has become poisoned by dangerous levels of arsenic, causing afflictions as grievous as cancer. Even the areas where water is potable today will fall victim to contamination in a few years if corrective steps aren’t adopted.

Yet the Bihar government’s response to the issue hasn’t been marked by promptitude. For instance, its Public Health Engineering Department has twice found excess arsenic in the groundwater samples of a few villages in Pashchim Champaran. But it refuses to notify the district as arsenic affected. Doing so would require it to paint arsenic-affected hand pumps red, alert the affected villages, put up information boards, create awareness among villagers, and provide alternate sources of drinking water – all of which need effort and resources.

Arsenic in groundwater

Groundwater is the primary source of drinking water in Bihar and the Public Health Engineering Department is responsible for both drinking water supply as well as sanitation.

“Before the 1970s, no one in Bihar had heard of arsenic in water. Dug wells were a common source of drinking water,” explained AK Ghosh, professor-in-charge of department of environment and water management at AN College in Patna, and an expert on arsenic pollution. “Thereafter, international agencies started pushing hand pumps, as water from open wells had bacterial contamination. With over-extraction of water through hand pumps, the problem of arsenic surfaced.”

According to Ghosh, arsenic has been present in the groundwater for a long time. Its source is the siltation from the Himalayas which gets deposited downstream through the Ganges. Arsenic, as it occurs naturally in the form of arsenopyrite (iron arsenic sulfide), is not soluble in water. But due to over-extraction of water through hand pumps (locally known as chapakal), the chemistry of aquifers has changed, releasing arsenic and iron and converting them into ionic forms. And, this ionic form of arsenic is soluble in water.

The World Health Organisation has classified soluble inorganic arsenic as “acutely toxic”, whose long-term intake leads to chronic arsenic poisoning. The effects, which can take years to develop depending on the level of exposure, include skin lesions, peripheral neuropathy, gastrointestinal symptoms, diabetes, renal system effects, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Till 2002, the Public Health Engineering Department didn’t even bother to test the groundwater for arsenic content anywhere. It was jolted awake only when Kunteshwar Ojha, a resident of Ojhapatti village in Bhojpur district, got his tube well water examined at Kolkata’s Jadavpur University after his wife and mother died of liver cancer. The report showed grave arsenic levels, higher than the “permissible limit” of 50 parts per billion set by the Bureau of Indian Standards.

Since then, the department has been testing groundwater, but there is confusion over arsenic-affected districts. The department’s website claims that 13 districts are affected, but, as per the Central Ground Water Board, there are 15 affect districts. Both the agencies do not include Pashchim Champaran.

Ghosh dismisses both set of data. “Eighteen of the total 38 districts in Bihar are affected due to high arsenic, including Pashchim Champaran...” said Ghosh. “Water sources that are safe today may show high arsenic in 3-4 years due to excessive withdrawal of groundwater. Continuous monitoring is needed to check the spread of arsenic in aquifers.”

He adds that while “mapping high arsenic areas of Bihar and high cancer rates in the state, we have found that the high arsenic areas report the highest cancer cases”.

Source: A K Ghosh, professor-in-charge, Department of environment and water management, A N College, Patna

Criminal callousness

Vinay Kumar is the secretary of Water Action, a part of the recently launched Jal-Janmat campaign. In 2006, Kumar was trained in groundwater quality testing (using Jal-TARA arsenic field testing potable kit) by Megh Pyne Abhiyan, a public charitable trust working on water and sanitation issues.

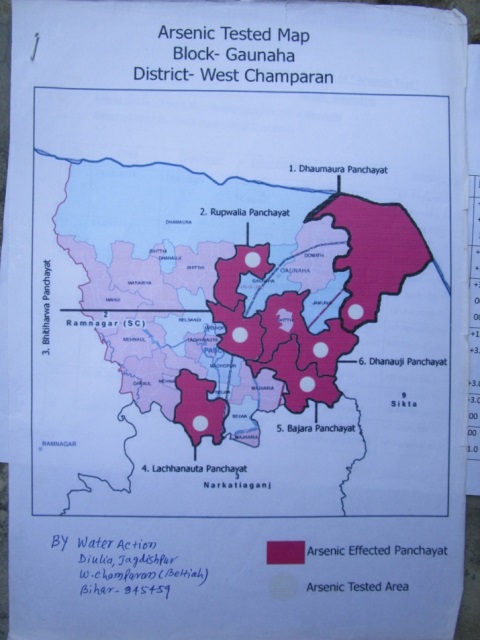

“In September 2011, Water Action and MPA jointly tested water samples from private and government chapakal in Gaunaha block of Pashchim Champaran,” informed Kumar. “Six panchayats reported arsenic levels between 10 ppb and 50 ppb.”

Kumar immediately approached the local PHED office demanding further water testing. Finally, this April, the Bettiah office of the department analysed hand pump water samples. The results: two villages in Domath panchayat (Gaunaha block) reported high arsenic – in Kairi, the level was 69 ppb and in Kairi Khakhariya 64 ppb and 58 ppb. Meanwhile, four water samples from Khap tola in North Telua panchayat returned arsenic levels between 67 ppb and 98 ppb.

Source: Water Action

Bhogendra Mishra, executive engineer, PHED (Bettiah), concedes that the department recently found high arsenic in two blocks of Pashchim Champaran. “Also, way back in April 2010, the department had found high arsenic in some water samples from Nautan block of the district,” he informed Scroll.in.

As per the 2010 test report, Budhwalia village and Khap tola in South Telua panchayat had 117 ppb and 300 ppb arsenic, respectively.

PHED’s Patna head office, however, says it is unaware of these reports.

“Some 8-10 years ago, PHED had tested groundwater, but did not find arsenic in Pashchim Champaran. Maybe now some tolas are affected, but we need proper scientific water testing before we declare the district arsenic affected,” said SN Mishra, executive engineer (monitoring) at PHED’s head office in Patna. He assured that deeper aquifers (150-200 feet deep) of PHED were safe.

Hydrologists disagree. “While drilling deeper, the shallow aquifer is also punctured,” warns Siddharth Patil, a researcher with the Pune-based Advanced Center for Water Resource Development and Management. “There is a high probability of the water, along with contaminants in shallow aquifer, leaking into the deeper water systems.”

While the government awaits more aquifer testing, millions of people in Bihar are forced to drink poison, as there is no alternate source of drinking water.

Credit: Ashok Ghosh

The horror of arsenic pollution magnifies at a closer look of the Indian standards for drinking water (IS 10500:2012), which is divided into “acceptable limit” and “permissible limit”. The acceptable limit of 10 ppb of arsenic is what should be followed for safe drinking water. But, in the absence of a safe drinking water source, a higher permissible limit of 50 ppb may be allowed. PHED conveniently follows 50 ppb.

“The BIS standard for arsenic is misleading,” said Ghosh. “WHO follows 10 ppb limit, Australia follows 7 ppb, and the USEPA [US Environmental Protection Agency] is considering 5 ppb as standard. If the guideline value of 10 ppb is followed, then a large number of hand pumps in Bihar will have to be painted red and sealed, as they are giving cancer to people.”

Nidhi Jamwal is a freelance environment journalist based in Mumbai. Her Twitter handle is @JamwalNidhi.