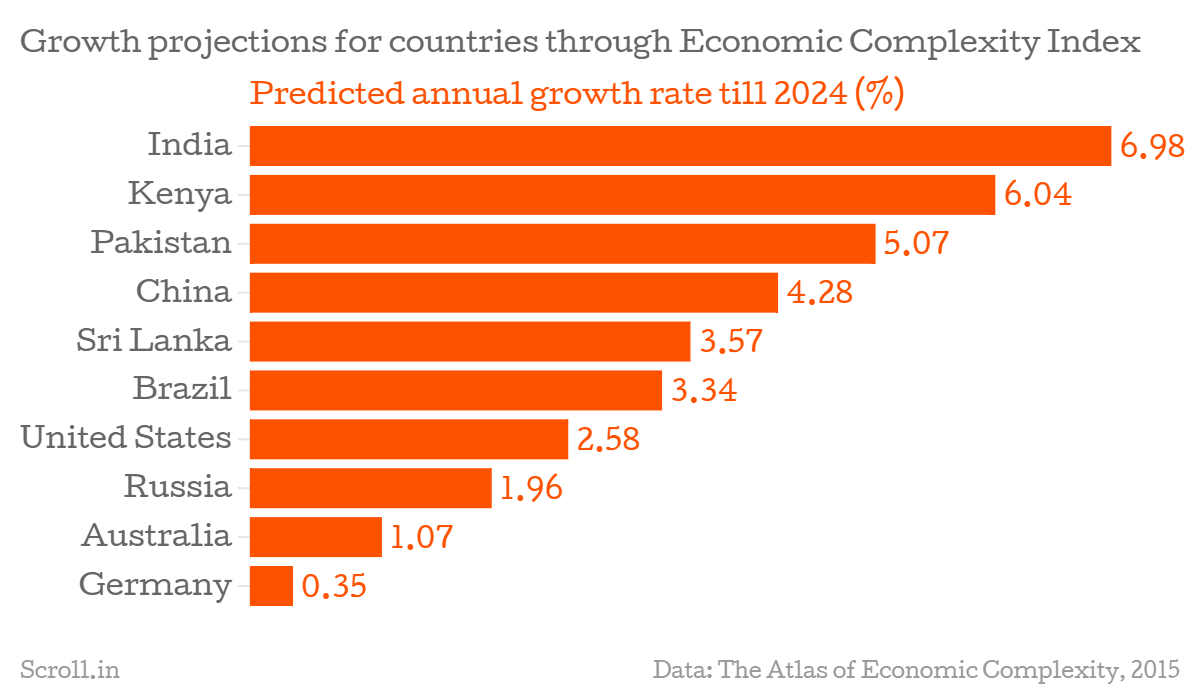

The Centre for International Development’s annual economic complexity index, which predicts growth rates by analysing exports and manufacturing diversity, has placed India at the top for its potential in the coming decade.

According to the analysis, economies in South Asia as well as East Africa show the highest potential for fast growth while oil-driven economies as well as those earning their revenues through commodities will face a slowdown in the next 10 years.

“India has made important gains in productive capabilities, allowing it to diversify its exports into more complex products, including pharmaceuticals, vehicles, even electronics,” writes Ricardo Hausmann, Professor of the Practice of Economic Development at Harvard Kennedy School, in the report.

If the Indian government's Mid-Year Economic Review is accurate, India remains on course to live up to the 7% prediction this year. The Review lowered its growth estimate for India’s Gross Domestic Product this year from the 8.1%-8.5% estimated in the budget in February to 7%-7.5%. That still falls within the range predicted by the Harvard researchers.

The researchers say they have studied the relationship between growth and the complexity of products a country manufactures and exports over several decades. There’s a high correlation between the two, they say, and argue that the index of Economic Complexity is much better at predicting growth for countries than other commonly used metrics.

“Sustained economic growth is fundamentally human-driven: the greater the diversity of productive knowhow in a place, the more the complex products it can make, which underpins income gains,” said Timothy Cheston, a researcher on the project.

India has jumped five spots in the Complexity Index between 2004-2014. It now stands at the 42nd position. Countries like United States, Canada, Brazil and Russia slid more than five spots each during the same period. China, however, jumped 16 spots and stood at the 17th position in the rankings.

The analysis expects India to “lead global economic growth over the next decade,” a conclusion that the government is likely to be happy to see.

To get there, however, the government will have to get past persistent questions about the quality of the GDP data, which even the Reserve Bank of India governor has expressed doubts about. It will also mean ensuring that the momentum generated when Prime Minister Narendra Modi took charge, coupled with the advantage offered by lower oil prices, is not frittered away.

Indications from this year suggest that industrial production has yet to pick up in any substantive way and exports have slumped for 13 consecutive months, implying the government cannot rest on the advantages identified by a team of researchers at Harvard University.