Back in the classroom, a young Nrupender Rao in Hyderabad got down to business, acing his grades, sitting in the front row and never missing a day of school. Sometimes, his teachers would end up missing class. When that happened, students were divided into groups and would quiz or debate

each other.

Once, when a teacher was absent, the principal sent Tulja Ram Singh, known as Pandit-ji, to oversee the class. Pandit-ji was a tilak-wearing faculty member who decided to test the students with something unexpected. The students were eagerly waiting for him to suggest a quiz or a debate, and he obliged – with a twist. He suggested that they debate – in any language of their choice.

The students squirmed in their wooden seats. Should they pick Hindi, which was being spoken as the national language, or should they stick to Telugu, which was the mother tongue for most? What if they chose to debate in a language nobody understood? Worse, what if the other side debated in a language they did not understand? Also, Pandit-ji was not a native Telugu speaker. Should they debate in a language he would understand?

As his classmates were floundering for a solution to the language issue (which, to be fair, still comes up from time to time, even at the national level, because not everyone has similar fluency levels in Hindi), Rao decided to have some fun. He stood up and began a memorable speech in Telugu. The gist of it was something like this: ‘You are a silly bunch, are you not? At best, you are as smart as straw, which is to say your intelligence is like that of a corpse.’ He continued in this vein, enjoying decimating his classmates, secure in the belief that the master could not understand Telugu.

Several minutes later, Rao finished and sat down. Pandit-ji then strode to the front of the classroom and proceeded to translate Rao’s invective into Hindi. Much to Rao’s embarrassment, Pandit-ji ended by saying he knew a bit of Telugu!

The class erupted in laughter, and Rao was red-faced but forced to smile. His stellar academic record got him a free pass that day, and he did not pay for his cheekiness. While the son was spending his time at school in the city and frolicking in rivers and soaking up the country life from time to time, the father’s political career was steadily progressing.

Even though J.V. Narsing Rao had practised law for some sixteen years, it was not to be the career that he would pursue in the long term. Politics beckoned the lawyer, and he was a stalwart of the Congress party in Andhra Pradesh. By the time he was forty, Narsing Rao had become the president of the Hyderabad Pradesh Congress.

As an elected leader, he began to consciously project himself as a flagbearer of unity and justice. These were things he had fought for as a lawyer and perhaps had their roots in the fact that he practised law in a country that was starting to architect itself after having gained independence. Despite being a part of the traditionally well-to-do Velama community and coming from wealthy antecedents in the Adilabad district in present-day Telangana, the lawyer-turned-politician had, by all accounts, a Gandhian penchant for khadi.

And, as Rudyard Kipling memorably said, he had not ‘lost the common touch’ despite being a person of some standing in society. He retained simple, everyday habits – including chiding his wife for keeping the electric fan on for too long. Not because he could not afford to pay the bills, but because he did not want to be seen abusing his privilege as a public servant by overindulging in using electricity.

Narsing Rao’s political journey progressed through twists and turns. His career, in many ways, mirrored that of Telangana, the state that had not been born then. But there was political tension simmering, as people wanted a destiny separate from that of Andhra Pradesh.

Before Independence, the princely state of Hyderabad could be loosely divided into three regions that were linguistically and culturally distinct. The Telugu-speaking Telangana region, which was about half the state, the Marathi-speaking Marathwada region (which became a part of Maharashtra) and a Kannada-speaking Gulbarga region, which went to Karnataka. Apart from this, there was an Urdu-speaking ruling minority.

When the British came to India, they signed a treaty with the then Nizam and acquired much of what is today coastal Andhra—areas north of Chennai. Post-Independence, much of the British-held territory was made part of Madras state and the Telangana region part of Hyderabad state. It was only in 1953, after Potti Sriramulu fasted to death for this, that a separate Andhra Pradesh for Telugu speakers was created. In 1956, through the States Reorganisation Act, the Telugu-majority parts of Hyderabad and Andhra Pradesh were merged into a unified Andhra Pradesh; the Marathi-majority areas went to the new Maharashtra state; while Gulbarga, Bidar and other Kannada-majority areas went to Karnataka.

From the early 1950s, the Telugu-majority regions had been fighting for a separate state – Telangana. The States Reorganisation Commission, on whose recommendations the States Reorganisation Act was based, had recommended the creation of a Telangana state.

There were a series of protests demanding the creation of Telangana state in 1955-56, but the Andhra Pradesh lobby in Delhi stymied this and kept Andhra Pradesh undivided till 2014. It is against this political and historical backdrop that Narsing Rao was carving his role. In 1969, Chief Minister Brahmananda Reddy reconstituted his ministry with twenty-nine members.

There were eighteen cabinet ministers and eleven ministers. JV Narsing Rao was appointed deputy chief minister of Andhra Pradesh. He was given charge of planning, roads, highways, public gardens, city waterworks and matters related to railways and communications.

Rao Sr was a product of both the Benares Hindu University and the Aligarh University – educational institutions that were not only highly ranked but also produced luminaries that ranged from heads of state to top lawyers, athletes and corporate figures. Narsing Rao undoubtedly made his political entry in the city, but it was in the grassroots and the hinterland where he would carve his legacy. As the chairman of the Andhra Pradesh state electricity board, he brought power to the villages of the state, especially the Telangana provinces.

While he was an important public figure, the frills and benefits of political office did not seem to have mattered to his son and his friends. Politics was never on the agenda. ‘My father never wanted us to enter politics. It was taboo for us. For the fifteen years he was a minister, not once did I go to his office,’ Nrupender Rao would later write. Why was that so? While neither Rao nor his siblings have a direct answer to that question, it is more than likely that the driving philosophy at the Rao home was to keep the Church (in this case home) separate from the state.

Rao’s sister Rekha agrees, saying that their father did not encourage his kids to come visit at work because he wanted to keep his family away from legal and political affairs as much as possible. ‘He was protective, especially of the girls, and he did not usually allow them to be around visitors from outside.’

Even as Narsing Rao navigated the choppy waters of Andhra politics, he never lost sight of what mattered to him – home and family. And that included a lifestyle that was far from extravagant. Life in Hyderabad in the fifties and sixties was casual, laidback, and leisurely. Younger people in most households would cycle around or sometimes take the bus. Private cars were not as common as they are today. The food, too, was simple. Rice, upma, dosa, idli and vegetables and dal, usually in the form of sambar, were what appeared on the Raos’ table – and indeed on the tables of most Hindu households in the region.

North Indian food had not become as ubiquitous as it is today, and even street food like samosas and chola bhaturas were not that easily found. Eating out in restaurants and clubs was something only the business classes and old-money families indulged in.

The young Nrupender Rao grew up watching his father balance the struggle for Telangana, new beginnings and the vicissitudes of public office. As the son of a newly minted minister, the young Rao could have grown up in an atmosphere of privilege and flamboyance, with a sense of entitlement that is often on display with the next generation heirs of modern-day Indian politicians in particular.

But Narsing Rao had a strong Gandhian streak, which was not only seen in his propensity for khadi. His children were brought up minus extravagance. The roadmap for the young Nrupender was not much different from that of any child born into an upwardly aspirational Indian family. There was no room for non-performance. And his father ensured a relentless pursuit of academic excellence.

Rao recalls that after his father’s appointment and elevation as a high-ranking official, they moved to a house that was reserved for ministers. ‘It was a large house with lawns, fruit trees and attendants. The previous occupant of the house was Laiq Ali, the Prime Minister of Hyderabad, who decided to leave for Pakistan,’ Rao recalls. ‘I had a room to myself in this house. My siblings and I also had the luxury of going to school in a car, and we stayed in the house for a few years.’

The house in Begumpet was posher than their earlier home. It was cut off from the main city, which meant that the young Rao and his friends would spend more time on a bicycle cruising around from school to each other’s homes. Sometime in 1956, Rao remembers, he wanted to see the offices of All India Radio where his friend Bhushan’s father was employed as an assistant engineer. All India Radio’s transmitting station was on the outskirts of the city in a lightly forested area called Saroornagar, which was home to smaller animals, including wild rabbits. Managers would shut down the station around 11 pm.

Rao and Bhushan visited the station, and Rao spent the night at his friend’s house. Like in many homes, Bhushan’s room had just one electric fan – an Italian Cinni brand table fan. So, after cooking Rao a dinner over firewood and eating in the open air, Bhushan slept in the verandah, leaving his fan-cooled room to his guest.

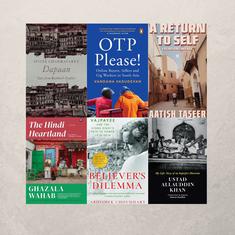

Excerpted with the permission from Forging Mettle: Nrupender Rao and the Pennar Story, Pavan C Lall, HarperCollins.