The ability of a country to raise capital in the financial markets is linked to its perceived creditworthiness and is a critical but underexplored theme determining its economic and social prospects. Investors typically rely on credit ratings to determine a country’s credit worthiness. If a country’s credit rating is lower than its credit fundamentals, as we argue to be the case for India, it invariably leads to higher borrowing costs, leaving less fiscal space for public spending on areas such as health, education, infrastructure, and climate resilience.

Credit rating agencies rate countries on a scale from AAA (highest rating) to D (lowest rating). India’s credit rating has remained unchanged at BBB- since 2006 by Fitch and since 2007 by S&P. This is the lowest “investment grade rating” (see Tables 1 and 2) and is just one notch above “non-investment grade ratings,” which are considered speculative and carry much lower expectations of debt being repaid. The same is true for the rating by Moody’s, except for a brief three-year period between 2017-’20, when Moody’s raised India’s rating by one notch to the equivalent of BBB, before reverting to BBB-.

Given India’s recent economic performance, it seems rather unintuitive that India’s creditworthiness has remained unchanged for nearly two decades. Here, we attempt to assess if India’s credit rating deserves to be upgraded based on the trajectory of its economic and fiscal metrics from 2006 to the present.

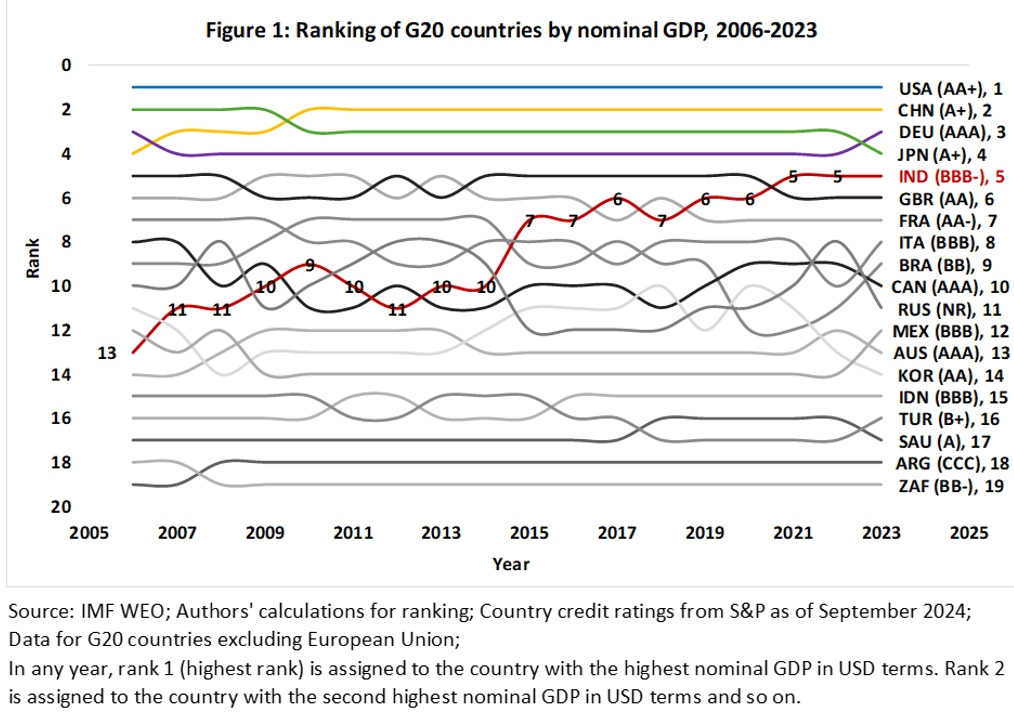

Rating agencies argue that credit ratings express risk in relative rank order, which means that a country’s credit rating is an outcome relative to that of other countries. Therefore, we compare the trajectory of India’s economic and fiscal metrics (since 2006) against those of Group of Twenty countries, a grouping that is intended to encompass the world’s most important economies. The G20 includes countries that are developed as well as developing and with credit ratings spanning the entire range from AAA to CC, making it an appropriate comparative sample.

Economic Trajectory: Relative to Other G20 Countries

In nominal terms, the Indian economy grew from the 13th largest in 2006 to the fifth largest in 2023, making it the only country in the top five rated below A+ and at the lowest investment grade (see Figure 1).

Fiscal Trajectory: Relative to Other G20 Countries

While recognising India’s growing economic strength, rating agencies argue that their assessment of India’s creditworthiness is largely constrained by weak fiscal metrics, ie, high debt levels and high debt servicing costs as compared to other countries rated at the same level as India.

For example, as of 2022 (the latest available datapoint), India’s general government debt-to-GDP ratio of 81.7% and interest-payments-to-GDP ratio of 5.2% are much higher than Indonesia’s (rated BBB) at 40% and 2%, respectively. However, this point-in-time comparison ignores the fact that the trend of India’s fiscal metrics between 2006 and 2022 has been more stable compared to most G20 countries that have observed higher increases in one or both metrics.

Figure 2 plots the relative change between 2006 and 2022 for debt burden and debt servicing costs of G20 countries. India is very close to the mid-point as its debt-to-GDP in 2022 is nearly the same (1.05 times) as in 2006. The same is true for interest-payments-to-GDP (0.97 times as in 2006). In comparison, most G20 countries have a higher ratio of debt burden (bottom right quadrant) or debt service (top left quadrant) or both (top right quadrant). Only three countries (bottom left quadrant) have lower ratios of both metrics.

Yet, it could be argued that while India’s fiscal metrics in 2022 are comparable to those in 2006, there could have been a large amount of volatility in between this period, pointing to fiscal mismanagement. To examine this concern, Figure 3 compares the trend of GDP, gross government debt and interest payments over the period (2006-’22), for select G20 countries.

It can be observed from the charts that India’s debt and interest payments grew at a similar pace as GDP almost consistently every year. In the case of China, debt and interest payments grew at a faster pace than GDP during the same period. In the case of the US, growth in debt outpaced GDP post 2008, whereas growth in interest payments outpaced GDP after 2021.

For most G20 countries, debt levels grew faster than GDP. However, developed economies benefited from near-zero interest rates post the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, allowing them to borrow much more cheaply. From 2008-’21, debt servicing costs for developed economies fell sharply even as debt and GDP levels continued to rise, maintaining the illusion of debt sustainability. The interest rate hiking cycle of 2021 led to a sharp increase in interest payments for these countries, in some cases, catching up to GDP growth. In comparison, India’s debt servicing costs did not outpace GDP growth, even though interest rates were well above zero and its credit rating remained unchanged.

Unlike developed economies, India did not have the luxury of lowering interest rates to near-zero, while simultaneously accumulating new debt. It nevertheless managed its annual interest payments at a level commensurate with its debt and GDP growth through the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the Taper Tantrum of 2013 (capital outflows triggered by the US Federal Reserve’s decision to scale back its quantitative easing measures), and the Covid-19-induced economic crash of 2020. This points to a remarkably stable fiscal performance across multiple political and economic cycles.

Other factors

One expected criticism here could be that credit ratings encompass more than just economic and fiscal factors. For example, rating methodologies also consider a country’s vulnerability to external shocks and subjective factors such as monetary policy effectiveness, among others.

It is noteworthy that in 2015, India implemented an inflation-targeting framework which brought down inflation from a historical average of 8% (2006-’15) to a post-inflation targeting regime average of 5% (2016-’23). External risks have also reduced significantly as Current-Account-Deficit-to-GDP decreased from an average of 2.4% (2006-’15) to 1.1% (2016-’23). It is also evidenced by a four-fold increase in foreign exchange reserves as compared to 2006, with India holding $704.9 billion as of the end of September 2024, the fourth highest reserves in the world (after Japan, Switzerland, and China, in absolute terms) and sufficient to cover more than ten months of imports.

Another factor to consider is the composition of the currency of public debt. The government of India’s debt is overwhelmingly domestic-owned, long-term, and denominated in the rupee, (94.9% as of the end of June 2024, per the Ministry of Finance), which drastically reduces foreign currency risks and interest-rate risks in debt servicing.

Conclusion

While rating agencies assess India’s fiscal metrics to be at relatively higher levels, there have been no signs of debt stress over the last 19 years, spanning at least three political cycles (five years per cycle) and two economic cycles (including three crises). At the same time, the country has grown rapidly, while also reducing its vulnerability to external shocks. Yet, during this period, India’s credit rating has remained unchanged at the lowest investment grade level.

It is becoming increasingly difficult to comprehend the reluctance on the part of rating agencies to upgrade India’s credit rating. While India’s debt levels are indeed higher than some peers, but India’s relative economic performance and fiscal discipline over the last two decades merits recognition, making the case for upgrades to its credit rating.

Sidharth Kamani is a Principal Risk Professional at the New Development Bank.

Shreyans Bhaskar is an Economist at the New Development Bank.

The article was first published in India in Transition, a publication of the Center for the Advanced Study of India, University of Pennsylvania.