A paranormal entity trapped in an ordinary prison: this has been chewy fodder for the authors of the fantasy genre. This entity, more commonly a djinn, locked in a lamp or some such contraption, will grant wishes, usually three, in exchange for its freedom. This trope, after featuring in One Thousand and One Stories has appealed to other writers and regularly crops up in the fantasy space. A great trope to show either the roots of greed or a yearning for freedom, it has come far from the milder versions. Now, the djinn is not always friendly, nor the master, always kind.

A djinn in Kerala

The idea that those who seek revenge must dig two graves is what loosely inspires Pranoy Mathew’s debut novel Lucy and the Djinn. The story begins with a car accident where Lucy asks for her djinn’s help to save her life. Mathew then takes us back to the beginning. Lucy is suffering from heartache. After a bad breakup, she arrives at the estate of her highly influential grandfather, the head of the Palathikal family, who has, unfortunately, died. His will is going to be read after the last rites.

We come to know Lucy as shy and introverted. Mathew describes her as such: “Lucy avoided crowds. She felt they judged her harshly and made her feel obnoxious for no reason. The very idea of walking into those strangers caused her face to flush and feet to sweat.”

It has to be fated that such a person eventually comes to meet a djinn.

Mathew brings the djinn to Kerala. He adds a sorrowful protagonist, greedy family members, MC’s need to seek revenge to get back at her ex-lover and voila, the stage is set for drama. He also deftly plants the seeds of nostalgia in the beginning. When Lucy is going to see the casket of her grandfather, she notices the vacant dog shelter where her German Shepherd Tipu used to reside. Next to it stood the dying Alphonso mango tree, the one she used to climb as a young girl. Mathew writes: “Her home had changed a lot, yet remnants of its past still lingered in the form of stubborn, unchanging objects.”

These lines are important as they will come again in the story, reminding Lucy of the spent days.

In the will of her mega-rich grandfather Zacharia (who started on the streets), Lucy is left nothing except a box sitting in the locker. In a note, Lucy is warned not to open it in public. Annoyed for not getting anything valuable, she goes to the bathroom to wash the lamp that has come out of the box. “Maybe I could auction it off in Bangalore,” she speculates.

When the djinn comes out and tells Lucy, “I am magic, the resident of the lamp. Named God, devil, djinn, I reign. Kingdoms rise and fall by my hand, but for thee I am a slave-a humble servant seeking a master,” she assumes she is going through another episode of hallucination induced by her post-traumatic stress disorder. In a hat tip to mental illness, Lucy suspects she missed her meds.

Apart from immortality, love and bringing the dead back to live, she can wish for anything. Lucy is too shocked to ask for a single wish, let alone three. The djinn tells her that humans always have something they want, even if they don’t realise it yet.

A thing called love

The story is rooted in philosophy. There is a constant commentary on human nature, their wants, the vanity and ephemeral lives they lead. Iblis, the djinn, tells Lucy that love is the strongest thing in the cosmos, one that transcends space and time. He says, “Does love’s essence reside solely within humanity’s embrace, or does it grace all beings with its ineffable grace? Love’s unyielding force binds all things as one – the planet to the sun, the moon to Earth and stars to the beyond. But man calls it gravitation, reducing nature to his limited perception, forgetting that each of them is a soul in motion, dancing to the rhythm of the cosmos.”

After Lucy recovers from her shock, she wants revenge on her ex boyfriend Adityan for betrayign her. The djinn tries to convince her with his philosophy: “You humans are a curious kind, thinking that you've come so far. Yet you move in circles, striving to define the infinite. You forget that you're a mirror of the universe's soul, a reflection of its every facet. Your love is love itself, the same that flows through the living and the dead, and we are all but a fleeting spark in its boundless expanse.’ But Lucy won’t have it any other way.

With each wish, Lucy not only dissects her past but also the djinn’s history. She sees her failed relationship and the why behind it. With every passing wish, the connection between the paranormal and the ordinary deepens and grows strong. She discovers herself and comes to tame her own demons.

I have a small grudge. Mathew leans heavily on philosophy, without shepherding the pace of the story. As a result, the story, between the wishes, screeches to a grinding halt. I hope he had also leaned more into the fantasy side of the story. It becomes conversational for longer periods and I wish there were more magic apart from an old TV coming to life and the djinn showboating with stars and planets upon his palm.

Leaving with my favourite lines from the book: “Oh, Lucy, we all have problems, we all suffer in our own ways – humans, djinns, demons, the gods. It’s a fundamental aspect of existence, there is no running away from it. And yet, it is through this very suffering that we would find ourselves, all of us, in our own ways and dimensions. sacrifice my life. Oh, Lucy dear, understand that life is a soul's fine test, a journey where we do our best. You should see beyond the flesh and bone, and realise that everyone is the same as they search for self and purpose.”

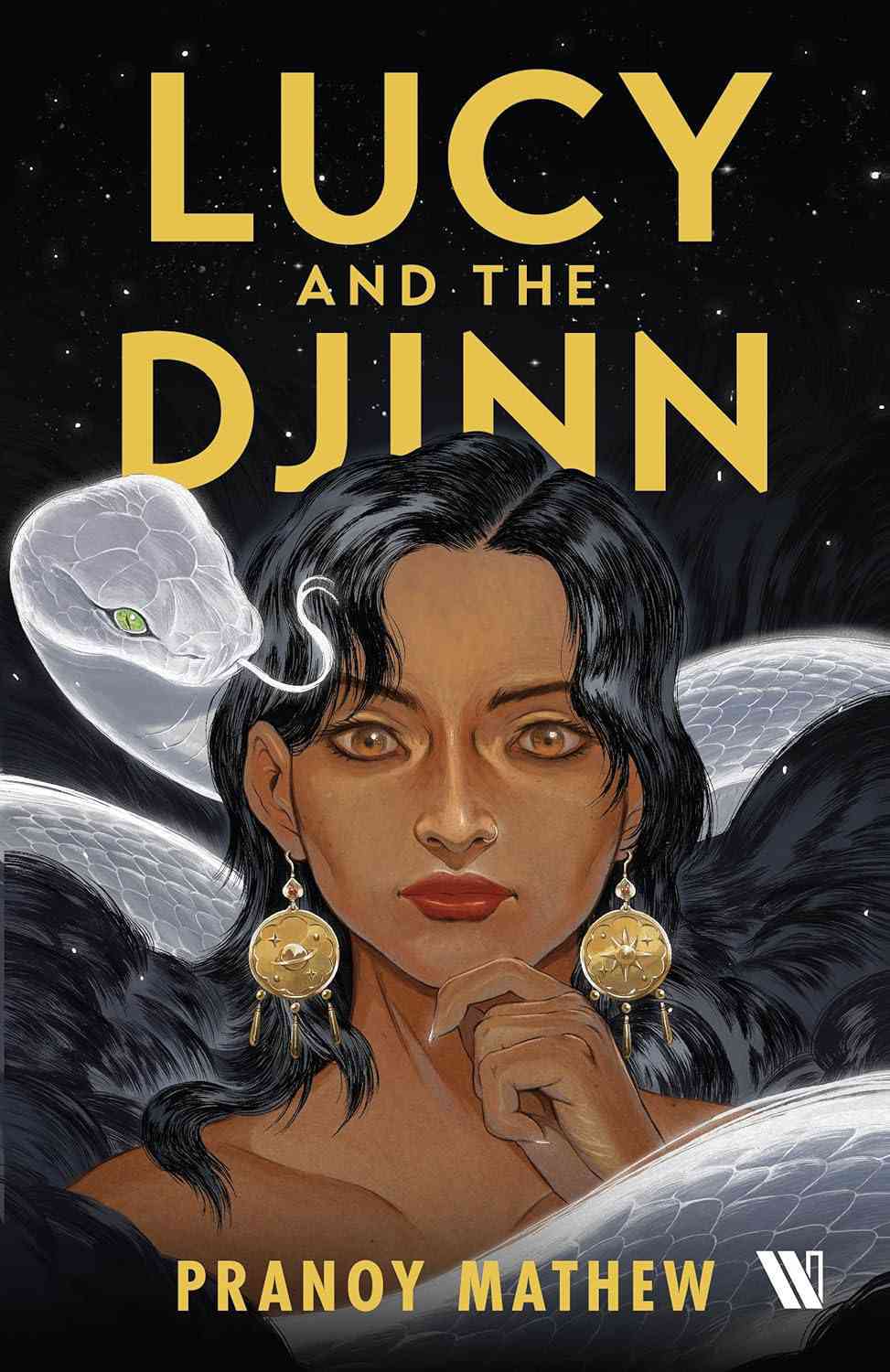

Lucy and the Djinn, Pranoy Mathew, Westland.