The Maulvi Saheb’s venerable beard was a source of never-ending wonder to Anwar. It was long and white, and as the morning breeze blowing from the Jumna played upon it, it assumed the most fantastic shapes. Now it was pointed like the tail of a sparrow, now it was blown about like the wings of a pigeon in flight; at one moment it was peaceful like a sleeping cat, and the next moment it would be wild like a stray street dog feared by all the children of the neighbourhood. It was fun to watch the old scholar struggling with his beard when an unusually strong gust of wind spread it fanwise, for then he would forget to scold the children for not attending to their Quran lessons.

Anwar’s body moved rhythmically backward and forward as he intoned the verses, continually repeating them, for great virtue lay in learning the Quran by heart – even if it was in a parrot-like fashion, without any understanding of a single word of the difficult Arabic language. The Maulvi Saheb did not fail to tell the children that this was the surest way of ensuring one’s place in jannat, the paradise where only the faithful may enter.

On the other hand, children who were naughty, who did not pay attention to their Quran lessons, or were disrespectful to the Maulvi Saheb were told that they were sure to be sent to jahannum, the hell which was uncomfortably hot, even hotter than Delhi in the months of May and June. Anwar did not like the hot summer when sweat simply poured from one’s body and every time one ventured out at noontime there was the danger of catching one’s death by sunstroke. There were compensations for this heat, of course. In summer he could drink cool sherbat and eat ice-cream – but then every time Anwar ate ice-cream his throat ached and he caught a cold and cough. That was why his father had forbidden him to touch not only ice-cream but even iced water and it was not possible to indulge the desire for them secretly, for the cough that was sure to follow would immediately betray him. On the whole, reasoned Anwar, it was better to make sure about going to paradise where it was always nice and cool, where rivers of milk and honey flowed, houris gambolled and birds sang in trees.

Who were the houris? Anwar had often wondered but his eight-year-old mind had been unable to find an answer to this question. They were women, of course. This much he had been able to gather from the Maulvi Saheb’s talk. But what kind of women? Were they like Phoopi Amma, the widowed and childless aunt who had brought him up ever since his mother had died while he was yet an infant? She had beautiful grey hair and was always dressed in white and spoke very little. Or were they like Gulabo, the old maid-servant, who was fat and black and sharp of tongue, but who prepared such tasty curries that Anwar’s mouth watered every time he even thought of them? These were the only two women who had entered his life but he found it difficult to think of them as gambolling houris. Or were they like those other women’ of whom Anwar had had but a fleeting glimpse?

Anwar’s sing-song intonation continued as his body swayed rhythmically. But the very thought of “those other women” brought a flush to his face. He remembered how one day, some months ago, he was walking along with his father on his way back from a shop in Lal Kuan Street to their house in Daryaganj. The boy trudged along, finding it very difficult to keep pace with his tall, long-legged father. From Lal Kuan they made their way to Hauz Qazi, then turning to the left they entered Chawri Bazaar. It was crowded though it was ate in the evening and the shops had closed for the night. Here and there a flower-seller was selling garlands of jasmine, calling out, “Lein phool chambeli ke.” Except for Anwar and his father, no one in the bazaar seemed to be in a hurry. They all walked at a leisurely pace, laughing and nudging each other as they looked up. There was something in the balconies overlooking the shops that seemed to be the centre of interest for everyone. Anwar’s eyes, too, involuntarily, glanced up, and there he saw in each little balcony – a woman!

Now these women were not in the least like Phoopi Amma or Gulabo. They were dressed in colourful clothes – reds and greens and blues – which fascinated Anwar. Their cheeks were all pink, their lips scarlet and their black hair sleek and oiled. The light of the lantern hanging near each one added to their allure.

One glimpse was enough to tell Anwar that these creatures were different to any he had met before and that they knew of some secret of life, some exciting mystery, of which he was completely unaware but which seemed to be shared by every one of the merry, carefree crowd in the bazaar. He meant to ask his father about these women but dared not, for the older man, aware of the boy’s upward glances, told him with unusual brusqueness – for otherwise he was gentle and patient with his son—that it was improper for decent people to look up towards the balconies while passing through this bazaar. After that they completed the rest of their walk in silence and Anwar did not dare to look up again. Indeed, since that day, Anwar’s father had made it a rule to come home by the more circuitous route via Ballimaran and Chandni Chowk whenever his son was accompanying him.

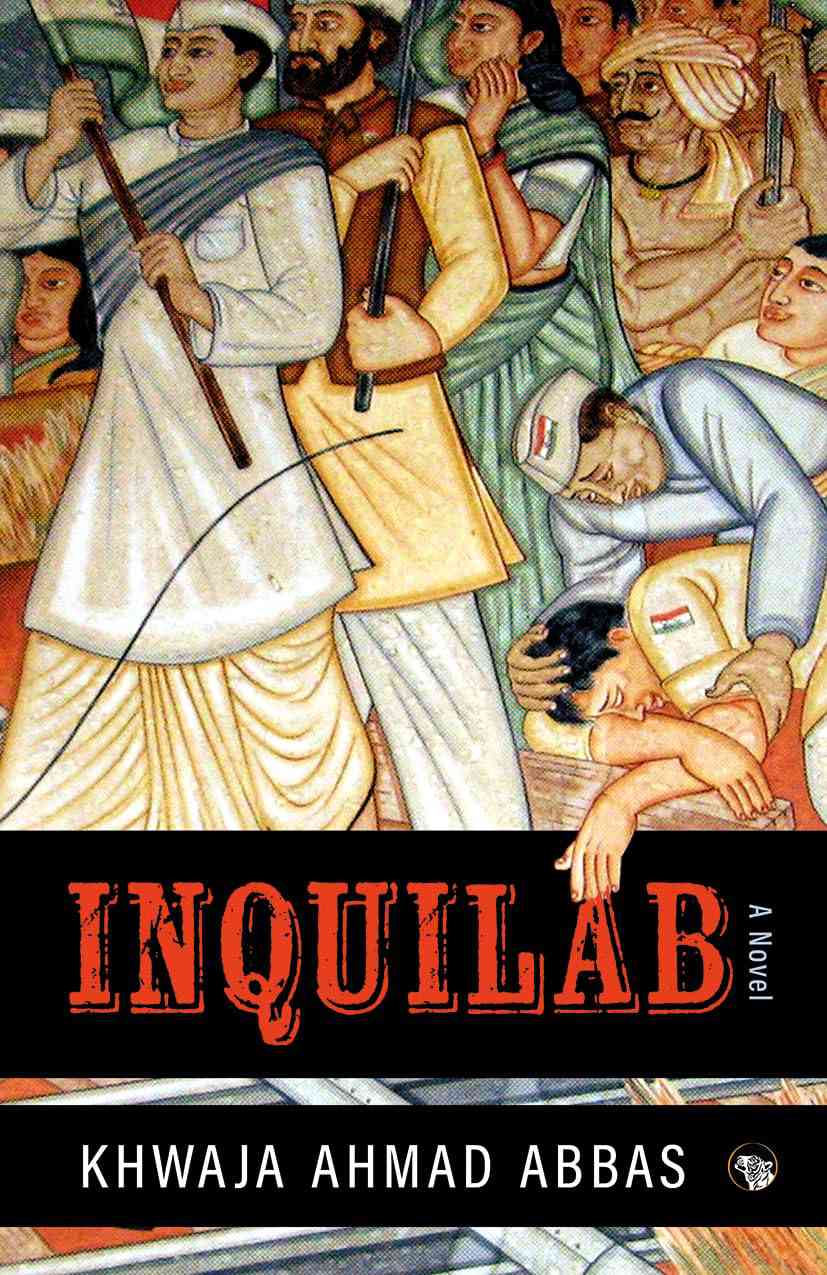

Excerpted with permission from Inquilab, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Speaking Tiger Books.