When I decided to settle in Bombay in 1970, I didn’t know I’d rise to soaring heights within a year. The heights can be measured. Their location is a flat on the 18th floor of a building in Cuffe Parade, a space that four members of the family, including myself, bought in 1970 itself; it was impossible not to.

Someone had booked the flat and then withdrawn, leaving it free just for us to take over, or so it seemed. As we walked in through the door into the vacant flat, the sea and sky rose before our eyes in dazzling splendour.

The view from the balcony overlooked a building with two Saracenic domes, beyond them a mill, a fishing dock and trawlers floating in the sea. The view clinched the deal for us. It would have been mad to look elsewhere.

I knew Mulk Raj Anand lived in the building with the Saracenic domes but I didn’t know in which part of the building. Sometimes I thought he had a whole floor to himself, sometimes I felt he occupied a room under one of the domes.

Used to living by myself for long periods at a time, and sometimes wanting to get away from the tumult of family life, I had the urge to visit Mulk, imagining that he surely lived under one of the domes, or at least that the room under one of them was his study. The visit never took place. Instead, he visited me.

He came with the artist Vivan Sundaram and the art theorist Geeta Kapur, whom I knew from our days in London.

I was touched and a little surprised by the visit. I had only a book of poems to my credit, he had several novels to his. Very few people had read my work though many people knew I was working on an anthology of Indian writing.

Or did the visit take place in or after 1974, when the anthology was finally available in India? Mulk wasn’t included in the anthology since he already had a fairly wide readership outside India, and one of the purposes of the anthology was to introduce lesser known or unknown writers (unknown to nonIndians, at least), especially through translations of their work, to non-Indian readers.

The visit went off well but had repercussions. I visited Mulk in turn (he doesn’t live under the cupola-like domes – they may have been cupolas once – nor does he have a floor to himself. He has a couple of spacious rooms on the ground floor of the building). It was much later that I realised that Mulk wanted me to visit him more often, especially in the evenings, when he would entertain several visitors, some of whom would drop in unannounced.

Running into me in the street one day, he reminded me of our first meeting, that it was he who had called first.

He thought it was discourteous of me not to have called on him more often. He told me he thought I was too arrogant and aloof ever to cross the street to see him.

Which perhaps I was, or still am. The truth is I dislike visiting people without an appointment, and am generally tongue-tied or resentful in the presence of strangers, some of whom, I’ve sometimes discovered in the course of an evening, may even have reasons to dislike me. I never knew what or whom to expect at Mulk’s.

The unpleasantness caused by this encounter has long passed and I have spent many pleasant evenings chatting with Mulk on the makeshift porch near the entrance to his rooms.

Often, from my eyrie on the 18th floor, I see brightly dressed young people dart through the gap between the gates of the building. I’m sure they must be visiting Mulk. (A tiny woman in red, a scarlet minivet perhaps, has just popped through the green gates.)

Hardly anyone else lives in the building. There was a move, not so long ago, to pull it down.

At ninety, Mulk himself is at least as agile as his young visitors, hopping in and out of trains with the gait of a school boy. His reputation as a novelist hasn’t weathered as well as he has but there are signs of a long-overdue reassessment.

I myself have grown to see the importance of his use of language – “pidgin” as he calls it – a conscious attempt to subvert the ruler’s English during a time of Empire, and after.

The coolies and untouchables of his early novels were also part of his overall strategy to make such invisible people visible, as much to British eyes as to our own.

Mulk believes in intervening in public issues, a busybody to some, a nuisance to others, but always an activist. We need people like him to remind us that without an active involvement in what is loosely called “culture”, important books will be allowed to disappear from view, just as precious buildings will be.

But I’m beginning to think the tide has turned, that the activists are winning, and that what will be allowed to go is only that which is no longer viable.

– 1997.

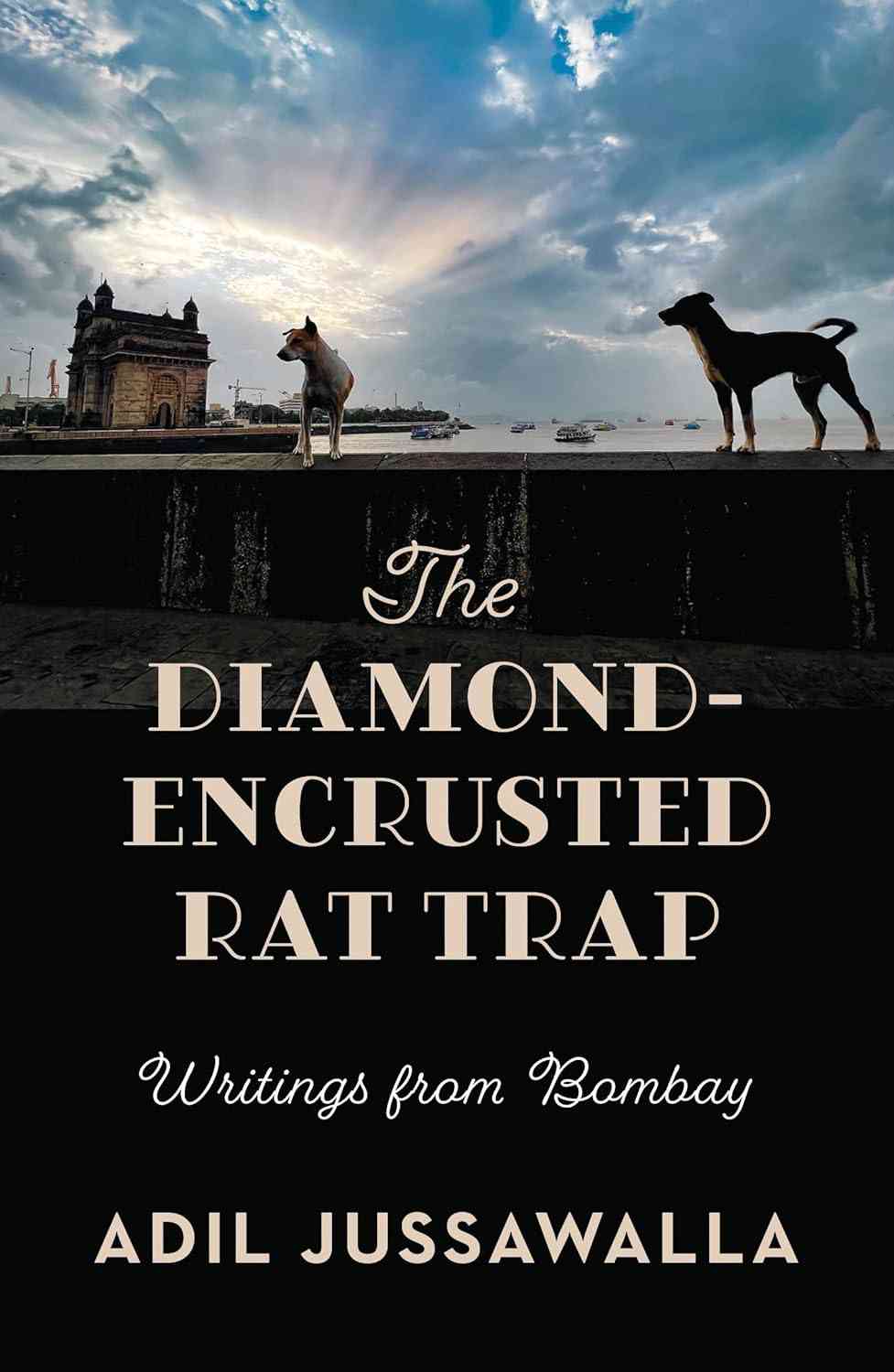

Excerpted with permission from The Diamond-Encrusted Rat Trap, Adil Jussawalla, Speaking Tiger Books.