Jyoti Bhatt was born in Gujarat’s Bhavnagar on March 12, 1934 – the fourth anniversary of the Dandi March led by Mohandas Gandhi. This coincidence always felt meaningful to him. Bhatt’s father was deeply influenced by Gandhi. That association may have shaped the outlook of the printmaker, photographer and teacher indirectly – and sometimes more directly, such as his decision to always wear khadi.

Bhatt, now 91, was especially struck by Gandhi’s advice to writers to use language so simple that even unlettered farmhands engaged in agricultural tasks could understand it. Bhatt says that he has always tried to follow this principle, especially in his writing.

The nonagenarian’s prolific artistic career and philosophies are being showcased at an exhibition titled Through the Line & the Lens at Gallery Latitude 28 in New Delhi. It has been curated by artist Rekha Rodwittiya.

This is the largest retrospective in recent years of the art and practice of Jyotindra Manshankar Bhatt, popularly known as Jyoti Bhatt. The exhibition offers a new reading of the enduring influence of Bhatt on an entire generation of post-independence visual art practitioners. Also on display are his personal writings in diaries and letters.

Bhatt’s lifelong vocation to document India’s living traditions, rural artistic practices and vernacular art forms has contributed significantly to preserving India’s visual heritage, says curator Rodwittiya.

“Bhatt understood that rural social practices were not going to remain intact and unimpaired from the changing economic and socio-political situations that India was encountering,” she said. “His travels brought him into contact with folk traditions, where art was practiced as part of the everyday occurrences of the lives of the people in rural India.”

While this could be viewed as a process of archiving and documenting, Bhatt’s keen creative approach makes them works of art in their own right, as well as a tool for preservation of the memory and a belief system he saw as slowly vanishing.

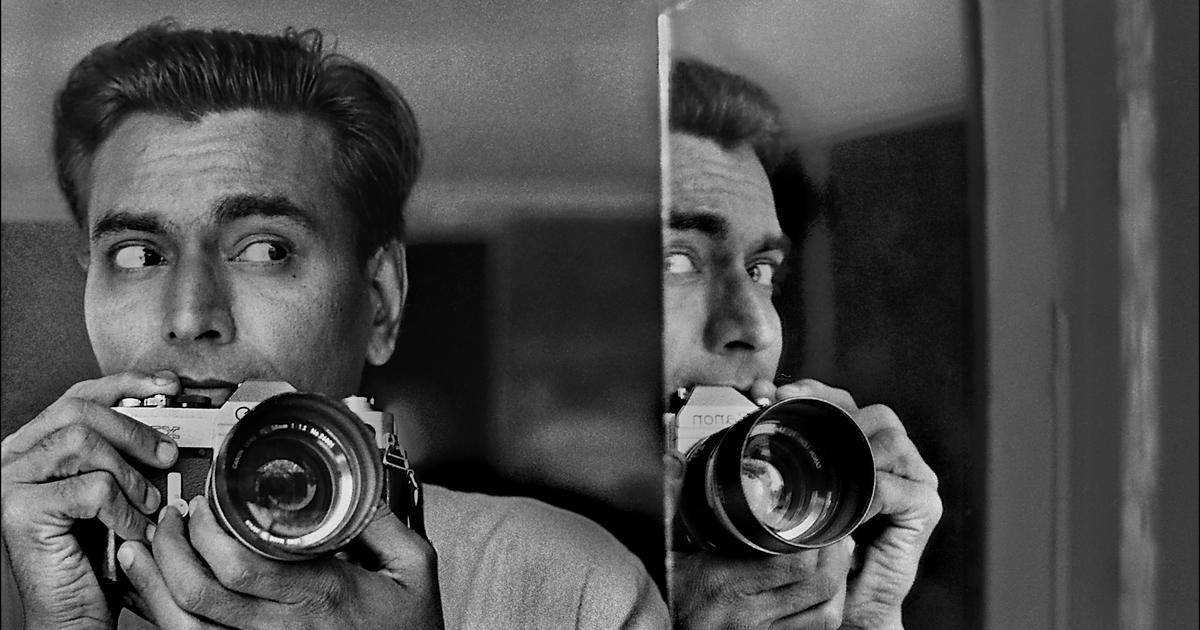

In 1967, Bhatt began using the camera to replace his sketchbook during travels, allowing him to record images immediately. Led by curiosity and experimentation, Bhatt used opportunities to explore new techniques, processes, and even technology.

Image making through the camera began as an act of documentation and a cerebral exercise, but gradually evolved into a medium of expressing emotions. A Gandhian at heart, he approached his work with empathy and humanism. His documentation of living traditions was far deeper than a mere record of events and scenes.

Bhatt’s practice straddled various disciplines. As an artist, he created a unique pictorial language that permeated many media in an era of seminal change within Indian contemporary art.

He was educated at Bhavnagar’s Home School, where the teaching philosophy was influenced by Rabindranath Tagore.

“The environment was liberal, even progressive, for its time,” Bhatt recalled. “Music, dance and the arts were given as much importance as subjects like mathematics or science.”

Since he was not particularly strong in academics, his interests grew naturally towards the arts. This led him to the newly established Faculty of Fine Arts at the MS University of Baroda in 1950. Here, Bhatt assisted his teachers, first NS Bendre and later KG Subramanyan, on their personal mural projects.

“Those experiences were formative and gave me confidence in my own ability to handle collaborative and large-scale work,” Bhatt said.

Attending events such as a fresco workshop at the Banasthali Vidyapith in Rajasthan in 1953 and his exposure to mandana, a traditional form of rangoli, gave Bhatt a familiarity with the form and a curiosity about it that later lead to his photo-documentation of similar living traditions in rural and tribal India.

He was exposed to printmaking during his college years. An exhibition of Krishna Reddy’s prints left a deep impression on him. Later, in 1964, when he received a Fulbright Scholarship, he studied the subject at the Pratt Institute in New York.

Bhatt began teaching at his alma mater in 1959. With limited resources and minimal access to information, it was a challenge for a teacher to open up the minds of young students.

“Looking back, I think I was playing a pretend game, like the ones young children play, by simply imitating how my teachers shared their knowledge of art,” he said. “Even then, and perhaps always, I preferred not to advise students on what they should do. Instead, I tried to make them aware of various possibilities, often drawn from the past.”

Situating India’s rural and tribal traditions within contemporary processes, as well as viewing Indian creative expressions in the context of Western and larger global discourses made Bhatt a unique bridge transcending the two worlds. While his work remained deeply rooted in the ethos of India’s history and heritage, it examined critically the dichotomies and ironies of Independent India.

At a time when most artists of his generation were aligning themselves with positions that reflected either Western or Eastern influences within their vocabulary, Bhatt did not conform.

“He deliberately becomes a tightrope-walker and juxtaposes his need to view both these territories as historical ancestries that accommodate him,” said Rodwittiya.

Positioned at the cusp between tradition and modernity, his work referenced cubistic attitudes and pop culture before arriving at the deeply rooted Indian folk characteristics. It reflects the socio-political environment and harmony and discord of Indian society.

His engagement with the complexities of modern India can be seen in his pictorial narratives, where image and text are often of equal importance to the cohesiveness of the image.

His work is still relevant, asserted Bhavna Kakar, the founder of Latitude 28. “Bhatt’s practice is foundational to many conversations that today’s younger artists are engaging with – whether it’s around identity, craft, documentation, or politics.”

Rahul Kumar is a Delhi-based writer on art and culture.

Through the Line and the Lens is on display at Gallery LATITUDE 28 till May 25.