Shakti [the first queer South Asian organisation in Britain] launched their newsletter Shakti Khabar (Shakti News) in 1989. We draw on the 17 issues of the newsletter published between 1989 and 1992, at the height of Shakti’s activity and activism. With a combined page count of well over two hundred pages (and well over 300 when combined with accompanying reports), Shakti’s publications contradict the myth that there is little or no material documenting the full range of political and cultural life and activism of queer South Asians in Britain in the 1980s. Collectively, the issues we looked at are held in the Camden Lesbian Centre and Black Lesbian Group (CLCBLG) Archive at Glasgow Women’s Library, Bishopsgate Institute (London) and the Bruce Castle Museum (Haringey Council, London).

We read Shakti Khabar in two ways: firstly, as Shakti’s own narrative act to fashion a queer South Asian identity from its location in Britain; and secondly, as part of a network of contradictory flows and transnational connections that contested what being queer and South Asian means. Despite the substantial interest in queer print culture, we were not able to find scholarly material that included considerations of Shakti Khabar. The return to black feminist print culture, especially from the 1980s, has offered new productive routes, from the reprint of classic collections such as The Heart of Race to new collections reprinting work from the Brixton Black Women’s Group, and new overviews of feminist print culture from black perspectives; however, Shakti and Shakti Khabar fall short in the different identity formations used to group and catalogue queer print culture.

This was queer organising that followed the map of workingclass South Asian communities. The Shakti Development Report for 1989–1990 documented remarkable progress in a short period of time. In their first year, they claimed to have reached over 600 South Asian lesbians and gay men. Their regular weekly meetings grew to 50–60 members, and the regular Shakti discos attracted over 200 attendees while generating vital revenue, which Shakti would continue to be dependent on alongside its membership and the sale of Shakti Khabar. Within its first two years, Shakti had a steering group to develop an HIV/AIDS response (SHARE) as well as a housing co-op for homeless South Asian lesbians and gay men (Shakti Ghar). Shakti was also in Leicester, and later expanded to Bradford, Birmingham and Manchester. Where there was a lack of research to advocate for policy changes within local authorities, Shakti responded to the issues within the community, producing evidence for longer-term change through doing the work. This was a motivating factor for creating Shakti Ghar: “Although there are nor [sic] proper statistics available at present to show the extent of homelessness within the Asian lesbian and gay community, our experience in SHAKTI shows that there is a great need for housing and that no agency at present meets those needs.” Shakti Ghar’s work articulated what everyone in the queer South Asian community knew, but which remained a minor or under-researched area for housing associations: “Homeless Asian lesbians and gays are ostracised or isolated from their communities which expose[s] them to the dual threat of racism and homophobia.”

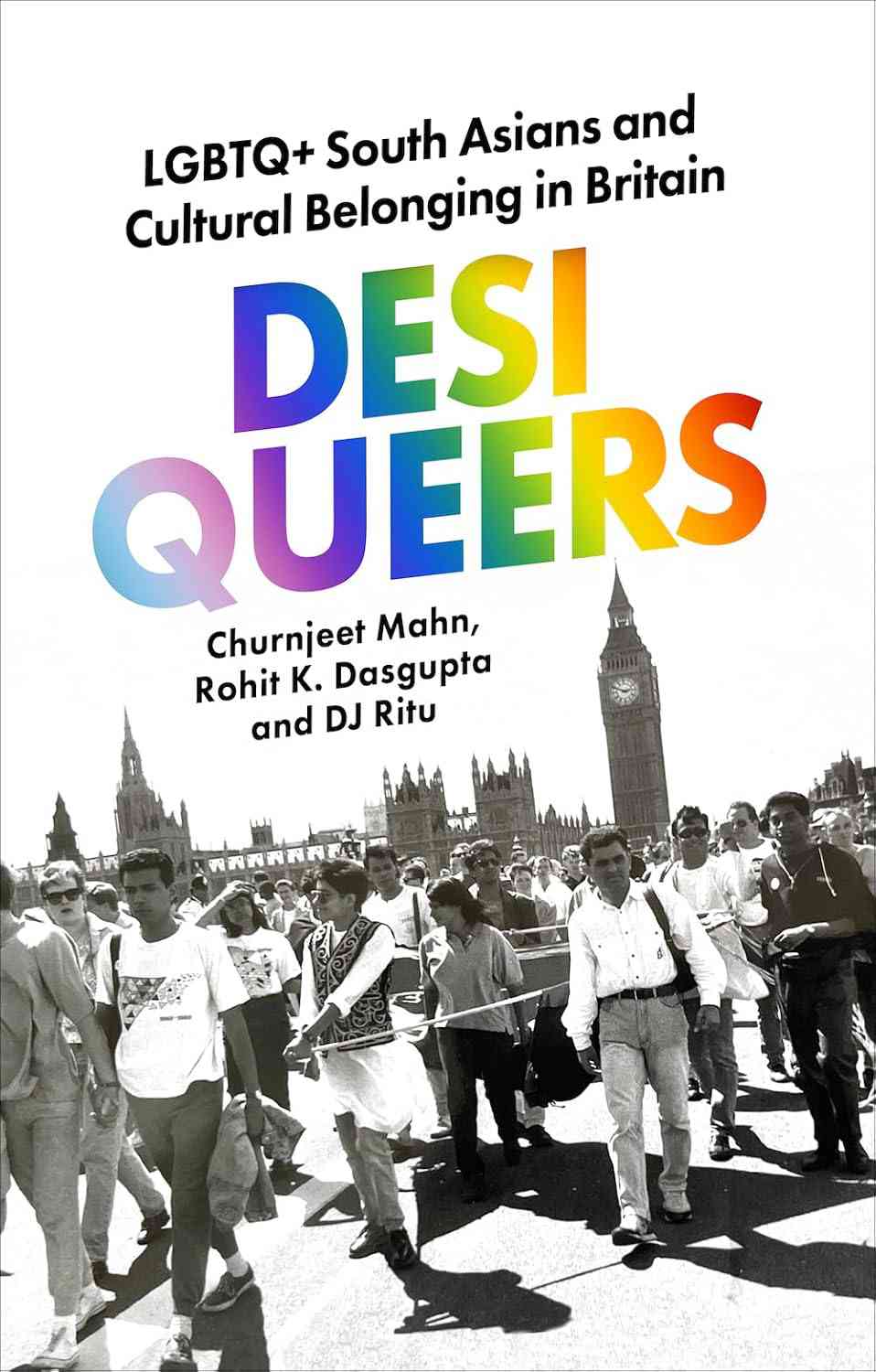

As artists and activists who already had experience with the mainstream media, it is no surprise that Shakti had a significant media impact for a new organisation. Network East, a British South Asian news and cultural affairs programme aired on the BBC, featured Shakti in 1989. In 1990, Shakti was part of a Channel 4 programme called “On The Other Hand”, which carried a segment on a South Asian gay man coming out to his mother. In 1990, Shakti members also led a discussion on gay and lesbian lives on Sunrise Radio, the London-based British South Asian radio station. In June 1990, Shakti marched for the first time in the Strength and Pride rally alongside Orientations (a Chinese and Southeast Asian group), the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre Project, and the Lesbian and Gay Black Group.

Shakti was not a minor part of queer organising in London, nor was it invisible within South Asian diasporas in Britain. Democratically organised with a rotating elected committee and a series of sub-groups, it was designed to respond to the interests and needs of its members. As Parmar reflected in 1993: “When I first came out 12 years ago, there were very few South Asian lesbians and gays around. We knew we are around and would travel hundreds of miles to meet. Now, 12 years later, we have Shakti, a very strong, over 1,000-member gay and lesbian group with a newsletter, regular meetings, and socials.” For some of the members, Shakti could rewrite the script of traditional South Asian family values by harnessing a collective energy bent towards the creation of a queer South Asian community. As one interviewee commented, “Just in terms of sharing about Shakti, I guess, it was like finding a family. It was very much like finding a family, and you know, and it was exciting, we were doing new things, we’re working together.”

While Khan remained the most prominent face of Shakti in its formative years, the labour of prominent social activists was felt on the pages of its newsletter. Even though there is evidence for gay newsletters in India prior to the publication of Trikone and Shakti Khabar, 10 desi diaspora newsletters and publications were a forum for connecting largely lesbian- and gay-identifying readers of South Asian heritage. For those born in the diaspora, letters and dispatches from India, Pakistan or Sri Lanka were queer glimpses into a world that may have only ever been relayed to them through those two loaded terms: our culture and our home, which seemingly placed queer life at an impossible distance when refracted through conservative and faith-driven conceptions of what being South Asian meant in Britain. For readers in Calcutta or Karachi, newsletters such as Shakti Khabar gave an insight into queer organising in Britain, as well as a practical means to spread the news about local meet-ups and new groups. More than once the pages of Shakti Khabar record readers from other parts of the diaspora arriving in India, details of a meet-up in hand, and coming along to a group.

Within two years, Shakti Khabar was printing a 16-page newsletter six times a year and had a circulation of 500 (with 100 copies being sent to South Asia and North America). Shakti Khabar was distributed for free in South Asia, via select university campus groups and personal networks, leading to a predominantly middle-class educated audience (which did not mirror the UK readership). Like many collective-based newsletters of the period, Shakti Khabar’s content was varied, although Khan was scrupulous in using his editorial privilege to challenge views which pathologised homosexuality. The newsletter’s advertisement page and its media coverage give a glimpse into Shakti’s impact in late ’80s Britain. Stonewall advertised roles for workers; Lesbian Line looked for volunteers; OnlyWomen Press (later Women’s Press) looked for contributions from South Asian lesbians; and a hotel in Scarborough announced its doors firmly open and welcome to Shakti members. Although its early issues did not include helplines for UK-based Black lesbian and gay organisations, they did include numbers for Trikone (the US-based queer South Asian group), Khush (the Canada-based queer South Asian group), and Paz y Liberacion (a US-based queer organisation for Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia), demonstrating Shakti’s changing orientation from queer politically black organising in the UK to transnational queer South Asian and brown networks.

Although based in London, Shakti Khabar’s reporting and content spent more time in India than Bradford or Birmingham. The “networking” section of the newsletter was dominated by men in India and the broader South Asian continent, seeking to connect to one another or establish friendships with others (mostly men) in the diaspora. On the one hand, this showed the importance of Shakti Khabar as a point of access to a global queer South Asian network that could facilitate the circulation of ideas, material, sex and routes to community-making. What gave Shakti its power was also the disturbance to its harmony: South Asian experiences of queer and trans sexualities in the subcontinent and Britain ran contrapuntally. Although Khan would sometimes intervene with an editorial gloss to link some of the contributions from South Asia with the social and cultural issues unfolding in Britain, the distance between these debates and observations was an accurate measure of how class, caste, faith, gender and geography created “impossible” conditions for a transnational queer South Asian collective identity.

Could gay liberation be something that changed and adapted as it moved across the world or were its only stable frameworks for identity incommensurate with social life in South Asia? Shakti Khabar’s first feature article captures the issues that Shakti would continue to grapple with: to what extent was it meaningful to discuss a global “gay liberation” movement when that term was so redolent with white saviourism? Issue 1 of Shakti Khabar (April/May 1989) featured an article by Sunil Gupta on nascent social groups for gay men in Delhi that organised along lines very distinct from Shakti. Speaking to an architect in Mumbai, Gupta touches on the segregation between access to sex and the literal and figurative spaces that desire needs: “He developed a more balanced sex life by sleeping with foreigners who had access to that all-important and rare commodity, private space. Since then he has been able to develop his own circle of Indian lesbian and gay friends, but the social scene whilst providing warmth and reassurance does not provide him with a framework to develop his gay identity.”

Shakti tried to build this framework through its work, but ultimately it would be unable to stretch across the queer valences of South Asian experience. The aims and objectives of Shakti included networking across queer South Asian diasporas, encouraging self-awareness, providing resources and support for queer South Asians, as well as creating new social spaces. But creating a balance between activists who had come of age through working-class anti-racist activism and people out to cruise for friends and lovers was almost impossible. This was a question mirrored in the formation of Trikone chapters in the US. In an article from Trikone-LA reflecting on their emergence, the author asks, “In the beginning, there was the dilemma of self-definition. Were we to be a social club? Should we stay away from politics and activism? (This was a moot question, since our mere existence is a political statement and our membership in a gay group brands us as activists. Yet this point was cause for discussion then and continues to be so today).” Part of the difference in London was the political and cultural environment for Shakti’s emergence. What was not different was how sex had the potential to rearrange social relations, especially between men.

Excerpted with permission from Desi Queers: LGBTQ+ South Asians and Cultural Belonging in Britain, Churnjeet Mahn, Rohit K Dasgupta, and DJ Ritu, Queer Directions/Westland.