In 2014, writer and academic Amit Chaudhuri wrote the mission statement on “literary activism” – as the starting point of the project. It began in 2014 with a series of annual symposia with Ashoka University. Its aim was to create a space for the kind of discussion on creativity no longer available in mainstream contexts (literary festivals, book launches) or in academic ones (conferences, classrooms, monographs).

Chaudhuri writes, “The idea of the symposium arose from a number of impulses: firstly, the belief that it’s no longer enough for writers to simply devote themselves to ‘creative’ practice and teach or study creative writing and have nothing to do with the conceptual underpinnings of their writing and their lives, any more than it is for academics in literature departments to simply produce monographs and shut out the problem of writing itself. Secondly, there’s been a feeling among many that there’s an urgent need for a conversation, and a forum, that goes beyond what you hear or encounter either at a literary festival or an academic conference. To achieve this one has to, on the one hand, eschew celebrity and book signings in favour of dialogue and response; on the other hand, steer clear of the closed professionalism of the conference and open out the conversation to people from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds who have a stake in the discussion.”

He got in touch with academics, novelists, poets, translators, and publishers and offered them the opportunity to speak on the subject in a way that they wouldn’t in other contexts. This established a pattern: an annual two-day symposium in India, and a one-day spin-off on the year’s theme at another location: twice in Oxford, and once in Paris. Since 2018, the symposiums have been supported by Ashoka University.

The Literary Activism website features a section called “Magazine”, in which new writing – essays, poetry, fiction – and art and videos are uploaded. Chaudhuri adds, “‘Literary activism’ is interested in the place of creative (whatever the genre or art-form) and critical practice today. […] A unidirectional flow – say, from London or Delhi or Calcutta towards Brooklyn – drains the life-blood for all involved. Making the flow go in other directions is essential not for the sake of balance, but for the intellectual viability of these practices.”

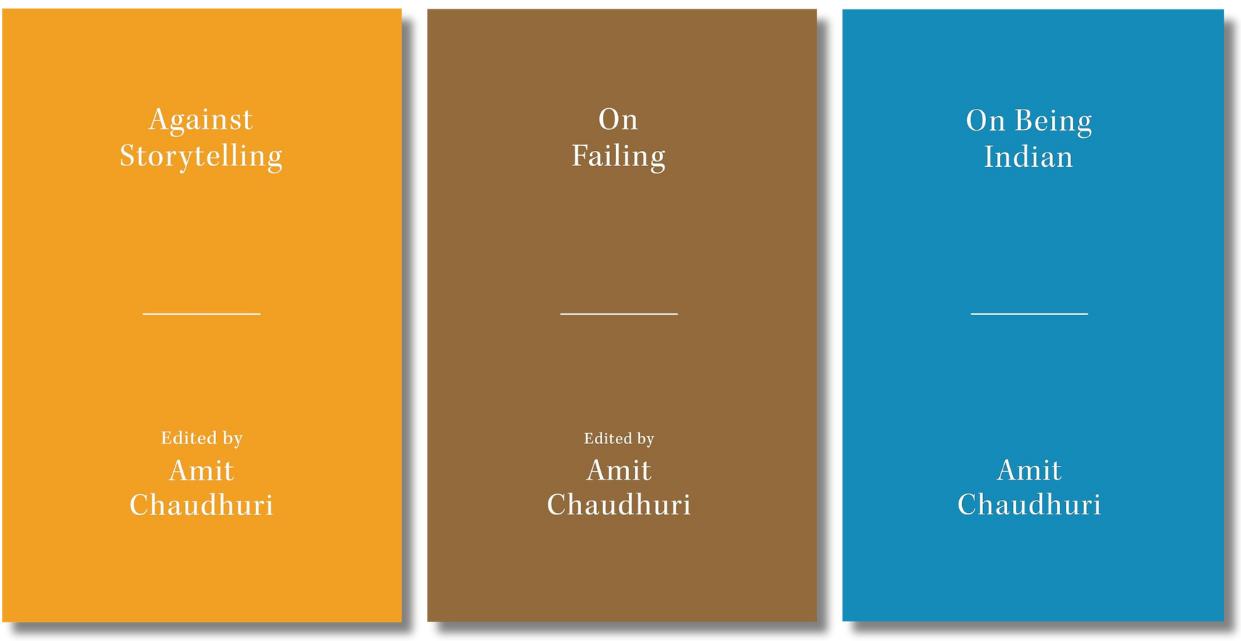

In 2023, Literary Activism, a new publishing imprint of the Centre for the Creative and the Critical at Ashoka University, partnered with Westland Books to publish three books a year under a collaborative imprint. The collaborative imprint publishes books on literature in English and in translation from other languages. The first book to be made available to the readers was Arvind Krishna Mehrotra’s Book of Rahim & Other Poems.

While launching the imprint, Chaudhuri had said, “The new imprint, ‘literary activism’, is meant to carry forward new ambitions in the realm of publishing. The imprint wishes to recall that art and writing are not synonymous with the generalised academic discipline called the ‘humanities’: they have an angularity to it, and to the social science perspectives the humanities are now subsumed under. The ‘literary activism’ imprint wishes not only to publish good writing, but to pursue this angularity.”

In the following conversation, poet and literary scholar Charles Bernstein, critic and biographer Jon Cook, writer and academic Laetitia Zecchini, and novelist and academic Saikat Majumdar talk about the importance of the project and how it has affected the creative–cultural concerns of their own writing since its inception more than a decade ago.

What were your first thoughts when you heard about the Literary Activism project?

Charles Bernstein (CB): That it was necessary. “Activism” is often associated with politics and surely political activism is necessary. But so is literary activism – conscientiously challenging the shibboleths and conformity that dominate literary awards, reviewing, and habits of attention.

Jon Cook (JC): Amit Chaudhuri is a friend and former colleague of mine. When he joined the University of East Anglia, we had some wide-ranging discussions about the state or states of contemporary literature. Out of these discussions, Chaudhuri’s analysis of the impact of both the marketplace and the academy on a certain way of writing and reading literature emerged. That analysis remains as pertinent now as it did ten years ago.

Laetitia Zecchini (LZ): Amit Chaudhuri once remarked that his first novel was born from the desire to write about a young boy’s “sense of escape and freedom” in Calcutta. This may well be Chaudhuri’s deepest impulse, and the driving force behind ‘“Literary Activism”. Through this project and platform, that is what he has given himself, and what he has given others as well: a sense of escape and freedom for those of us who feel a certain dissonance or discomfort with particular fields, discourses and platforms, and with the hierarchy of values they reinforce. In my case, the academic world which increasingly rewards visibility, citation counts, self-promotion (and self-importance!), buzzwords and “buzz-genres”! But once academia is dictated by arithmetic success, quantitative impact, and competition – once it becomes a field of power in a sense – it doesn’t just lose its purpose, it also becomes tedious.

Saikat Majumdar (SM): I knew Amit Chaudhuri for quite a while by that time and also knew of his discontent with the literary culture of our time trapped between the dishonest commercialism of the mainstream and the narrow instrumentalism of academia. So it was exciting to see him launch a series of interventions to do something different.

What made you agree to be part of the project? Were there intersections of intellectual ambition and creative-critical concerns between your work and the Literary Activism project?

CB: I admire the work of Amit Chaudhuri, as an essayist and literary activist as much as a poet and novelist. We saw the strains of “literary activism” in each other’s work. Coming perhaps from different cultural spheres, East and West, we found we had more in common than those closer to hand. So, this gives me confidence that we can have a non-national exchange, and I use that word rather than trans-national or even international. We are beside one another.

JC: I liked its openness to a variety of contributions from writers, academics, artists, film-makers, etc, and the resonance of the topics chosen for each of the symposia. I have a long-standing interest in the relations between the creative and the critical in my work as a critic and biographer, so, yes, there were many intersections. I felt we needed a new way of thinking about literature and its value in a period after the dominance of literary theory and the emergence of creative writing as a university discipline. The Literary Activism project offered a route into this new way of thinking.

LZ: What I find so compelling, so necessary about the literary activism platform/project is that it has also restored a sense of delight: the delight in listening to one another and in thinking together; the delight in witnessing the unfolding of critical thought and minds; the delight in paying close attention to texts and to voices, and the delight in the discovery and the encounter of many new texts, voices, personalities; the delight also in being able to say, or hear and share: “I don’t give a damn” (remember: “f*ck storytelling”!)

SM: As a writer who is part of academia, but also someone who works in the literary sphere run by mainstream presses and newspapers, this felt personally connected to me. As someone who writes novels, scholarly criticism, literary essays and op-ed articles, I’ve long ceased to see any difference between the critical and the artistic. They are for me simply different genres of imaginative writing, such as poetry, prose, and verse. The Literary Activism seemed to feel the same way, and brought together people who felt likewise.

Why do you think the Literary Activism project seemed urgent, timely and necessary ten years ago? What has it achieved, if anything at all, in these ten years?

CB: In my most recent book, The Kinds of Poetry I Want: Essays and Comedies, I included several key works from Literary Activism: three short works of poetics and a long essay “Up Against Storytelling” that comes in response to Chaudhuri’s conference on that subject. So “Literary Activism” has become one of the main forums for my work.

JC: See above for my thoughts about timeliness and urgency. It has created a space between the academy and the marketplace where there can be serious, witty, open-minded thinking about what it means to write now and what needs to be resisted if a certain idea of literary value is to be both defended and developed.

LZ: Chaudhuri has been able to gather around him a community of wonderfully talented people who, precisely, do not take themselves seriously, but who delight in each other’s company. It’s also in many ways a community of friendship. In the symposia that he organises, there is a real spirit of conviviality, and there is often humour as well, but it never comes at the expense of the gravity and sometimes the difficulty of certain questions and discussions.

For me, that space of “escape and freedom” – even just knowing it exists and persists: 10 years! – has been deeply sustaining.

SM: Literature is the most intellectual of all art forms and the most artistic of all intellectual discourses. Consequently, literature and creative writing have easily found a core place at the university, amidst academic disciplines – more than filmmaking, visual or performative arts. This has also made it vulnerable to the malaises of academia. On the other hand, as an art form (at least in principle if no longer in reality), it has also inherited the ailments of the free market as we have moved through neoliberalism. These peculiar features and locations of literary culture made the Literary Activism project timely ten years ago – and it remains timely 10 years later as both academic and free-market cultures continue to move through transformative crises in the 21st century. Already facing this transformative crisis early in the 21st century, literature had more identity problems than one could imagine, and the Literary Activism project had put its fingers on several of them. It has certainly achieved the reality of a persistent set of interrogations. I would love to see it taken up more organically by different stakeholders in literary culture worldwide.

What are the things you'd like to see Literary Activism being involved in?

JC: I’m not sure it needs to be involved in anything but its own development. There is a valuable website called Literary Activism and an associated book imprint. It might be worth connecting with them to raise the profile of the thinking underway in the Literary Activism project. But I don't want to lose the polemical edge of Literary Activism. The danger of market hyperbole is matched by the bland conformity of academic discourse. The LA project successfully resists both.

What are your thoughts, if any, on the Literary Activism imprint?

CB: The books extend the work of the meetings and the website is a necessary way. Because, in the end, books still serve to ground our discourse.

JC: It strikes me as a valuable initiative.

SM: I think we are becoming people with rapidly receding literary and cultural memories. We’re now ruthlessly presentist, and almost immediately, ruthlessly futurist too. But literature and culture are nothing without the past, and memory and affection for it. One key thing the Literary Activism imprint does is to revive thoughts, archives, and books that we need to remember and re-remember. This is something I tried to do with a column I wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books from 2020 to 2022, “Another Look at India’s Books”. The books published in the new imprint are exquisite, and the plainness of their covers is a bold statement.

What does the Literary Activism project – and its timeline – say about our literary culture?

CB: We are in a post-post-colonial world. Those of us working with “Literary Activism” are peers engaged in exchange. For me, that means learning more about West Bengali literature and culture, and more generally Indian culture – beginnng to have a deeper and more resonant sense of the full resources of 20th century thinking and poetics. So then, in the 21st century, I am less hamstrung by the pervasive parochialism and underdevelopment of American culture. “Literary Activism” wakes me up to the world.

JC: The marketisation of literature and writers continues with very little understanding of what might be lost in this process. Since the Literary Activism project began this has been increasingly informed by the presence of social media and, more recently, AI. In the process a certain kind of literary experience is likely to disappear. We need to resist this disappearance and the Literary Activism project offers a way of doing so.