The term “north-east” in its simple lexicographical sense indicates a direction – and raises the question north-east of what? The answer to the question in the case of Indian history and culture is simple: north-east of the Gangetic plain and peninsular India. But the term cannot be restricted, in the case of India, to merely its dictionary meaning. Northeast India – or in shorthand just the Northeast – has come to denote histories and cultures that are distinct from those of the Indian heartland.

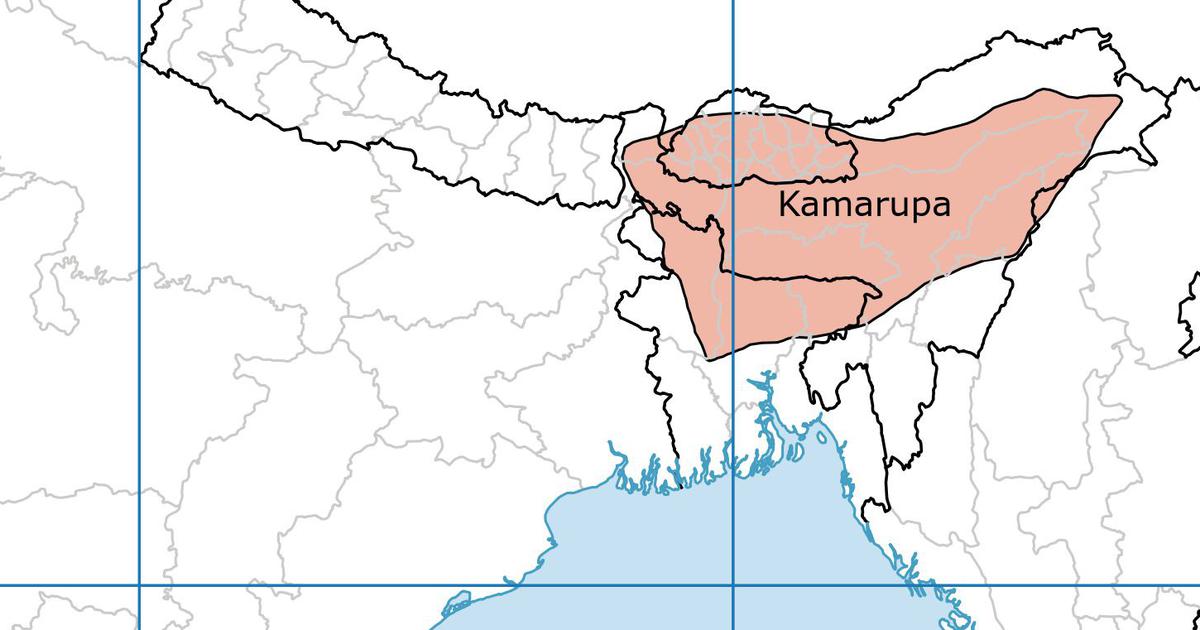

As things stand today, the Northeast consists of seven separate states – Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura. Each of these states has its distinctive culture and history. But in the past, before the Indian republic fashioned these seven states, this vast geographical territory was referred to as Assam, which harked back to the land of Kamrup, which stretched from the eastern points of the Brahmaputra valley to the river Karatoya.

In the early 13th century, Kamrup, already in ruins, saw the arrival of the Turko-Afghans from Bengal, and the Ahom settlers from Upper Burma. From this period to the coming of the British in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, this area did not see any centralised ruling structure. Political authority was fragmented – tribal state formations, and non-tribal and armed landed sections of the population known as Bhuyan or Bhaumik exercised power. The dominance of the Bhuyan was concentrated in the western and central parts of the region.

One of the more important tribal formations was that of the Ahoms. They used the plough and made their own village settlements and established their authority over other tribal villages. The Ahoms were ruled by a king chosen from the royal clan; the king allocated domains to the nobility but the king could also be removed by the council of great nobles. The system was thus based on loyalty and service. The two other major tribal formations – the Chutiyas and the Kacharis – were either subjugated or pushed back to the southwest by the Ahoms who also pushed westward at the cost of the Bhuyans. These were processes that occurred in the 16th century.

Another tribal state formation was that of the Koch which during the 16th century established its power in the western part of the region from the Karatoya to the Barnadi. In 1562, the Koch were powerful enough to march to the Ahom capital of Garhgaon and sack it. But the power of the Koch dissipated when the kingdom split into the Koch-Bihar and the Koch-Hajo. The latter overlapped with the western part of what is today known as Assam. In the Khasi Hills there emerged in the 15th century the state of Jaintia.

Under the dispensation of the Koch and the Ahoms, the Bhuyans were absorbed into the official class and formed an elite. They could attain this status because of their knowledge of the scriptures, measurements, and arithmetic, and their ability to use arms. The Bhuyans were mostly high-caste migrants from North India who wielded considerable local political authority. Some of them were Muslims. Their power base was control over land and over armed tenants whom they could mobilise. Sometimes they formed partnerships against a common enemy.

The Bhuyans were very often pioneers in land reclamation and in dyke-building activities for water control. The Koch-Hajo areas were subjugated by the Mughals but this was not permanent. The Ahoms in 1682 annexed the Koch-Hajo areas. This meant that Ahom control extended right up to the Manas River. The conflict between the Ahoms and the Mughals opened up the region to external influences. In economic terms, since the Ahoms knew the use of the plough, there was a shift among the tribal populations they subjugated to permanent cultivation.

The use of the plough and the prevailing ecology facilitated wet rice cultivation. This is not to say that hunting and fishing and other tribal occupations disappeared in a geography where forests and swamps were prominent. Increasingly, however, the rice economy gained in importance.

Under the Ahoms, the militia (regular members of the civil population trained to serve as a military force) played a crucial role in the extension of rice cultivation by reclaiming land, settling the population, and building embankments as safeguards against floods. The land was also carefully levelled. An observer in the second half of the seventeenth century wrote, referring to the lands the Ahoms controlled: “In this country they make the surface of the field and gardens so level that the eyes cannot find the least elevation in it up to the extreme horizons.”

During the course of the 16th century, the Vaishnava movement became very popular in the region and by 1700, there were around 1,000 monasteries (sutra). The latter also enhanced the process of land reclamation and the extension of cultivation. The monks sought for themselves exemption from obligatory military service to the state. There was a period when the Ahom state attempted to suppress the monasteries and force the monks to join labour camps to build roads and embankments. But this was a passing phase. By the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Ahom state was making revenue-free grants of wastelands to the monasteries.

Originally, the militia system was not very coercive but from the reign of Pratap Singha (1603–41), coercion became an integral part of the militia. The entire male population, with the exception of serfs, priests, and those of noble birth, within the age group of fifteen to sixty, was expected to be part of the militia. The system was organised in such a fashion that at any given point of time one-fourth to one-third of the militia was available for work. In the Koch and Kachari kingdoms and also in the neighbouring kingdoms of Jaintia and Manipur a somewhat similar system operated.

Excerpted with permission from A New History of India for Children: From Its Origins to the Twenty-first Century, Rudrangshu Mukherjee, Shobita Punja, and Toby Sinclair, Aleph Book Company.