Most investors would do well to invest in equities through equity-oriented mutual fund schemes. However, if you have the time, inclination, and flair for directly investing in equities, you will find it profitable to do so.

As a beginner, you can learn the tricks of the trade through a virtual portfolio available freely on broker websites. By incurring only trading costs, without committing money, you can understand the market. It prepares you for the real battle ahead.

To invest directly in equities you need (a) a basic level of financial knowledge, (b) confidence in your abilities, (c) a certain commitment of time and effort, and (d) a certain corpus of investible funds to create a diversified portfolio. If you don’t satisfy these conditions, you should resort to indirect investment in equities through mutual funds.

To invest on your own, you have to learn the basics of fundamental analysis and become familiar with some elemental tools of technical analysis. This chapter seeks to briefly discuss these two approaches to stock selection and offers some guidelines that will serve you well.

The stock market is thronged by investors pursuing diverse approaches. The two most commonly followed approaches are the fundamental approach and the technical approach. The basic tenets of the fundamental approach, which is perhaps the one most commonly advocated by investment professionals, are as follows:

There is an intrinsic value of a security and this depends upon underlying economic (fundamental) factors. The intrinsic value can be estimated, albeit roughly, by a penetrating analysis of the fundamental factors relating to the company, industry, and economy.

At any given point in time, there are some securities for which the prevailing market price will differ from the intrinsic value. Sooner or later, of course, the market price will fall in line with the intrinsic value.

Superior returns can be earned by buying undervalued securities (securities whose intrinsic value exceeds the market price) and selling overvalued securities (securities whose intrinsic value is less than the market price).

To estimate the fundamental value of a share, the analyst must estimate the firm’s future stream of earnings and dividends. The worth of a share is equal to the present value of all the cash flows expected to be received from it. This means the analyst must forecast the firm’s revenues, operating costs, depreciation charges, tax burden, investment requirements, and so on.

Basically, the analyst must be able to divine the future. This is a daunting task. As a manageable proposition, the analyst assesses the overall macroeconomic environment, analyses industry prospects, examines the company’s financial statements, and interacts with the company’s management. The analyst hopes that a study of all of these factors would provide some valuable insights about the company’s future performance which is not yet reflected in market prices.

Basic determinants of intrinsic value

The fundamental analyst focuses on the following basic determinants to estimate the ballpark value of a stock:

The expected growth rate

The expected dividend payout

The degree of risk

The level of market interest rates

Since the general prospects of a company are strongly influenced by the profit potential of its industry, security analysts typically start by studying industry prospects. Indeed, in almost all investment management firms, security analysts specialise in certain industry groups.

Expected growth rate

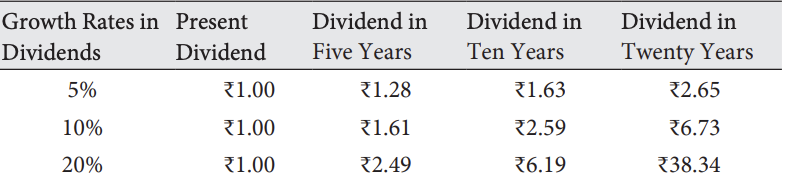

Most people don’t fully appreciate the power of compound interest, which Albert Einstein once described as the “greatest mathematical discovery of all time”. Similarly, the impact of various growth rates or the size of future growth may not be clear to most people. The table below illustrates how varying rates of growth influence future dividends.

It may be possible to sustain a low rate of dividend growth for a long period, but it may be well-nigh impossible to sustain a high rate of dividend growth for a period beyond 15 years or so. Industries and companies have life cycles similar to those of most living beings. Even if a natural cycle is not an obstacle, as a company becomes larger, it is harder to maintain the same rate of growth.

Although there are difficulties in forecasting, share prices reflect differences in growth rates as perceived by the market. Furthermore, the expected length of the growth phase is very important. These considerations are reflected in the following rules of fundamental valuation:

Rule 1: The larger the growth rate in earnings and dividends, the higher the value of the share.

Rule 1A: The longer a growth rate is expected to last, the higher the value of the share.

Expected dividend payout: As a shareholder what you receive is dividends, not earnings. So, dividend payout matters: other things being equal, the higher the dividend payout, the higher the value of the stock. Note the qualifying phrase “other things being equal”. A stock with a high dividend payout ratio may not be worth much if the growth prospects are bleak.

On the other hand, the stock of a company that is in a dynamic growth phase is valued more highly, even if it is currently paying out little or none of its earnings. Of course, between two companies with identical expected growth rates, the market values more the one whose dividend payout is higher.

Rule 2: Other things being equal, the larger the proportion of earnings that is paid out in dividends, the higher the value of a share.

The degree of risk: Risk is an important factor in the stock market, even if your enthusiastic broker may brush it aside. Risk has an important bearing on valuation. A stock with more stable and predictable earnings is deemed to be a high-quality stock – or a “blue chip” stock in the trade jargon. Hindustan Unilever is a good example. Such stocks command a premium valuation in the sense that they trade at a higher price-earnings multiple. On the other hand, a stock whose earnings are volatile and unpredictable is deemed to be a poor-quality stock or risky stock. Such a stock typically trades at a lower price-earnings multiple.

Rule 3: Other things being equal, the riskier a company is, the lower the value of its share.

The level of interest rate: The stock market does not exist in isolation. Investors look at the stock market in relation to investment opportunities elsewhere. If they can get a stable return of 5 to 8 percent from their investment in fixed-income instruments such as bank deposits, government bonds, and so on, they would obviously expect a return of 12 to 16 per cent or so from the stock market. After all, they want to be compensated for the risks of equity investing. On the other hand, if the return they can get from fixed-income instruments is lower, their expectation from the stock market would be correspondingly muted. The return they expect from equity investing is the discount rate they apply for capitalising future dividends. This leads to the last rule of fundamental analysis:

Rule 4: Other things being equal, the lower the interest rates, the higher the value of a share.

Obstacles in the way of an analyst

The four valuation rules suggest that a stock’s fundamental value (and its price-earnings multiple) will vary positively with the company’s growth rate, the duration of growth, and the dividend payout ratio, and negatively with the riskiness of the stock and the general interest rates.

While such rules are very useful in suggesting a rational basis for establishing value, investors must bear in mind the following obstacles they encounter in practice:

Inadequacies or incorrectness of data

Difficulty in forecasting

Irrational market behaviour

Inadequacies or incorrectness of data: An analyst often has to wrestle with inadequate or incorrect data. While deliberate falsification of data may be rare, subtle misrepresentation and concealment are common. Often, an experienced and skilled analyst may be able to detect such ploys and cope with them. However, in some instances, he too is likely to be misled by them into drawing wrong conclusions.

Difficulty in forecasting: Forecasting future earnings and dividends is a hazardous exercise. Future changes are largely unpredictable, more so when the economic and business environment is buffeted by frequent winds of change. In an environment characterised by discontinuities, the past record is a poor guide to future performance. Although stock market pundits claim to see the future, they are as fallible as others. As Samuel Goldwyn once remarked, “Forecasts are difficult to make – particularly those about the future.”

Irrational market behaviour: The market itself presents a major obstacle to the analyst. On account of neglect or prejudice, undervaluations may persist for extended periods; likewise, overvaluations arising from unjustified optimism and misplaced enthusiasm may endure for unreasonable lengths of time. The slow correction of undervaluation or overvaluation poses a threat to the analyst. Before the market eventually reflects the values established by the analyst, new forces may emerge. As Benjamin Graham put it: “The particular danger to the analyst is that, because of such delay, new determining factors may supervene before the market price adjusts itself to the value as he found it.”

The mathematical precision of fundamental value formulas may be beguiling because it is well-nigh impossible to estimate accurately the four drivers of intrinsic value. You can only make informed guesses about them. There is a fundamental indeterminateness in the value of a stock.

Excerpted with permission from Mastering Personal Investments: 20 Steps to Financial Independence, Prasanna Chandra and Savita Shrimal, Bloomsbury.