It was two days after the beating. I felt submerged in deep pain; it literally hurt to get up in the morning. That first minute of movement was the worst.

As the day wore on, especially when I was sufficiently distracted by other concerns, I got by well enough. But all it took was a cough or a sneeze and the full force of the injury – and the insult – would return. Fucking Boris! I wanted to hurt him. Hurt him bad. But first I had to avoid any repeat of the mauling I received two days earlier. Or indeed, anything worse.

The effort to keep my wounds – in all senses – hidden from Helen only added to my strains. Still, I could not resist the impulse to hide this episode and its marks from her.

I turned onto my good side and observed her. She was asleep with her mouth slightly parted, looking as innocent and vulnerable as anyone in that state. Why was I keeping my latest troubles a secret from her? Was it embarrassment over my financial troubles, or shame at becoming Boris’s bitch?

A loud screech on the street followed by the rapid-fire exchange of slurs broke into the calm coolness of our little apartment. Good morning, New York! It was my cue to leave bed. Rising early was never my forte. Besides, as the one who usually closed the shop, it was expected that I sleep in a bit. But since the beating I was trying to shower and dress before Helen, to reduce her chances of glimpsing the blue bruise on my ribs, as amorphous in shape and as diffuse in its shades of violet as a modernist painting.

By the time I sat down at the little bistro table that served as our dining – and indeed all-purpose – table with the day’s first dose of caffeine, Helen came out, eyes puffy and hair ruffled. Her favorite white sleeping shirt hung loose on her slim frame. Her blonde curls fell in lush but ruffled plenitude on her shoulders. I was always struck by her beauty, even when she was at her most natural, least made-up, and unaffected.

“You’re dressed already?”

“It’s bill day,” I said dully.

“But you’re going in now, this early?”

It was only 9 am, and we didn’t usually open shop until 10 am. “Yeah, I really need to look through stuff. It’s tight this month.”

I hated letting slip that ugly truth first thing in the morning. Helen stood with arms crossed over her chest, and one foot planted on the other. I could tell she still felt the morning cold from waking up. I wanted to give her a hug but stayed in place.

If the debt, or rather its repeated default, made me feel unworthy, the beating left me feeling downright dirty.

“Anyway, I gotta go,” I said. I rose abruptly without finishing my coffee but was stopped short by a sharp pain shooting down my bad side.

“What happened?” Helen said as she rushed over to me. “Did you pull a muscle?”

“I’m fine,” I said, stretching my arms outward to preempt any touching.

Helen looked taken aback.

“Babe,” I said limply with no further explanation for my odd behaviour.

“What’s going on with you?” Helen asked, her voice as full of concern as it was of puzzlement.

“Nothing, nothing,” I lied. “It’s just the pressure of it all, I guess.”

Helen and I were two nobodies, who had connected over our desire to belong. People who were adrift, people like us, could still find a berth in New York, as pirate ships did in rogue ports. Our shared sense of being not just outsiders, but unwanted, felt like the pull of destiny. But my odd secretiveness in this time of mounting pressure was taking a toll on our relationship. I felt that I was trying to preserve an idea of who I wanted to be to Helen. And my early training as a man, and especially one in any relation to a woman, was so flawed that it had left me fundamentally fucked up. To be raised in a repressive Muslim culture, with overlays of Victorian-era puritanism, was not auspicious grounds for training in a romantic career. The more I cared for someone, the less I felt I could tell them what I truly felt or wanted. Especially if it revealed any flaws or weakness. I wanted to be infallible in their eyes. I wanted their unmitigated approval.

“You have to tell me,” Helen said. “Whatever it is, you know you can tell me?”

But how could I? My failings had escalated our financial crisis into existential jeopardy. I was already carrying the marks, and I knew that I had exposed Helen to physical harm. I could not see how I could admit to that. I felt too ashamed. I needed to fix things first, so there would be no risk to Helen.

“Oh, what’s there to say?” I said, completing my rise to full height. “You know everything. It’s just exhausting. We are doing everything right now. Still, it’s never enough. We can never catch up.”

“I know, I know,” Helen said. She came closer and touched my face. Her fingers felt cool against my warm skin. Even after a night of sleep, she exuded a fresh smell, like a whiff of pine and juniper in late autumn. And momentarily transported me to a sense of safety, of well-being.

“I have to go,” I said. In a voice more of resignation than of fight.

“It’s going to be okay,” Helen said. “It’s always okay.”

“How do you know?” I could not help a tinge of irritation in my voice.

I wanted to believe her, but the hope of a more plentiful future was now badly, pardon the pun, bruised for me.

“Because I grew up with this. Constant shortage of money. Creditors banging on our door. Collectors towing away our car. Stores refusing credit. Stitching shit together to wear. Repairing things all the time, never replacing. And, yet we survived. Even had fun.”

I was not the only one to come from rough beginnings. Continents apart, we had both been raised with many of the same stresses, similar privations. I shook my head. Even through the hardship of her upbringing, I didn’t think she – or her parents, meaning her listless mom and ever-troubled but always-there stepfather – ever faced the level of threat that Boris now posed for us.

“Besides, remember, what do I always say?” She was smiling with such relaxed confidence.

“Nothing ever happens,” I said, chuckling a little.

“That’s right, nothing ever happens – except birth and death.”

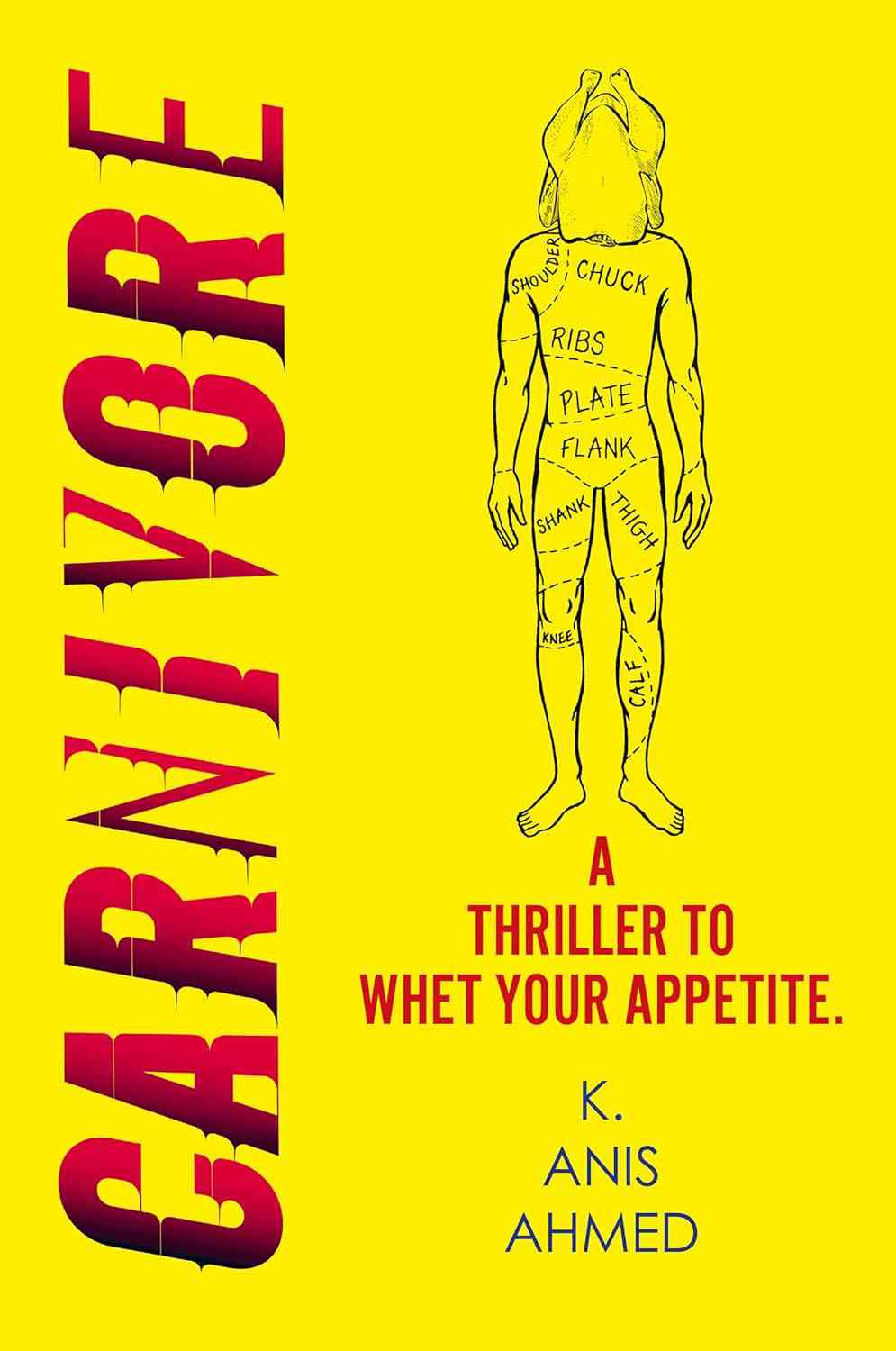

Excerpted with permission from Carniovore, K Anis Ahmed, HarperCollins Publishers.