Holi 2003 at 7, Race Course Road was special. When Vajpayee came out onto the lawns to meet ministers and well-wishers, someone placed a pagri on his head. One by one, everyone smeared colours on his face and kurta. Putting formality aside the ever-stern Yashwant Sinha sang out-of-sync Holi songs, complete with a dholak. The prime minister was made to move his feet and hands to dance a little. Even if he looked clownish and a little frail, there was no mistaking the cheer and relief on everyone’s face.

They were ringing in a milestone, at once personal and historical. Atal Behari Vajpayee had completed five years in office, and would finish his term – the first non-Congress prime minister since Independence to pull this off. There was no more talk of resignation or immediate succession, no rumours of cancer. In his 79th year, he walked slowly, his ears bearing heavy hearing aids. But he had voluntarily cut down on fried and sugary foods, and shed 4 kilos. Some of the motivation may have come from Rajkumari Kaul’s heart attack the previous March.

He looked slimmer, more relaxed and confident, more in command. He seemed willing to embrace his many contradictions, determined to enjoy the last lap: he aimed higher. He knew this would be the “last chance for talks, at least in my lifetime”. Leadership in early 21st-century Asia no longer needed map-makers; it required the foresight to resolve old disputes by calculated compromises, to settle the old-drawn maps. The only way a modern prime minister could vault to the tier-I list was to steer through moments of crisis.

He wanted to attempt to resolve Kashmir, to which the possibility of an American war in Iraq had added yet another layer of complication. Bush wanted to safeguard his country against “the conjoined threat of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction and links to terrorist groups”. At first, Vajpayee gave Bush the benefit of the doubt, urging Iraq to “abide by the UN resolutions” and destroy the weapons of mass destruction “that it is alleged to possess”. But the UN inspected over 300 sites, and did not find any evidence of WMDs. Old-school American conservatives like Kissinger were blunter, and they justified the invasion of Iraq, saying toppling the Taliban was not enough: it hadn’t fully scratched the American itch for revenge against Islamic extremists. The rest of the world saw it mostly as a futile and reckless war based on poor intelligence – a war that risked further destabilisation of West Asia.

For India, the costs of such a war far outweighed the benefits. It was dependent on Gulf oil, and inflation was bad news for a government seeking a fresh term. The crisis also brought home the strategic nature of the oil sector, stalling the privatisation of HPCL and BPCL. The centre would have to arrange for the safe return of 4 million Indians working in the Gulf. Indian Muslims, wary of the saffron party after the Gujarat riots, were unanimous and vocal in opposing an American capture of Baghdad.

Meanwhile, Bush took great delight in mocking the UN. The US introduced a resolution in the Security Council demanding that Iraq surrender all WMDs by 17 March, only to withdraw it on the last day for fear of defeat. Two days later, Bush invaded Iraq. The American president saw himself executing god’s will by converting the dictator-run Iraq into a Western-style democracy. Most other countries did not want to fight America’s war based on Bush’s interpretation of the Bible.

On the eve of the attack, Vajpayee was goaded in Parliament into taking an unequivocal position: “The use of force by a superpower to change a regime is wrong and cannot be supported.” Afterwards, the MEA released a statement declaring that the military action “lacks justification”. Bush called up the next day to ask Vajpayee to tone down India’s opposition. The Western coalition toppled Baghdad on 9 April, forcing its old dictator, Saddam Hussein, to go into hiding. The resolution adopted in Parliament a few weeks later used the strong word “ninda” of Hindi, meaning censure; the English version merely “deplored” the US action.

Vajpayee did not want to antagonise Bush, not the least because the Americans were mediating between India and Pakistan. Visiting the Valley on 18 April, primarily to lay the foundation stone for development works, he tucked in an extempore speech. For the first time since militancy broke out, a prime minister spoke in public in Srinagar. Standing behind a bulletproof podium at the Sher-e-Kashmir cricket stadium, he made an emotional plea: “We have come to share your pain and grief.” He urged Kashmiris to shed the acrimonious, unrealistic goals of the past to look ahead towards a peaceful future. He had come prepared with a doctrine: Insaniyat, Jamhooriyat, Kashmiriyat. Humanism, Democracy, and Kashmir’s age-old legacy of religious amity. Even if this was mostly atmospherics, the three principles offered a framework for the way ahead.

At the Kashmir University convocation the next afternoon, he extended another olive branch: “If Pakistan announces today that it has stopped the cross-border terrorism, I will send a senior MEA official to Islamabad tomorrow.” He invoked the impact of the Iraq war as a “warning [to] the entire world, specially the developing countries … It is now important that we resolve our differences through dialogue”. It was not clear whether he was aggrieved over the humiliation of a friendly Asian nation by a rowdy superpower in flagrant disregard of the UN, or simply cashing in on the prevailing anti-American sentiments. Perhaps it was a bit of both.

One could overlook the hidden irony behind Vajpayee privately seeking American intermediation only to condemn their foreign policy in public. It was a neat policy somersault: he had not discussed it with the CCS. The invitation to Pakistan came as a “huge surprise” to his foreign minister. When the prime minister was shown an op-ed by an American commentator suggesting he was a Nobel Peace Prize contender, he was less than thrilled. You really think all of this is to win the Nobel, he said dismissively: “Kya main yeh sab Nobel jeetne ke liye kar raha hoon?”

There was another way to interpret his initiative. It was subtly directed at his domestic constituency – a bid to temper the Sangh Parivar’s growing push to replicate the Modi model beyond Gujarat, which fuelled hatred of Muslims and Pakistan. Peace inside the home and on the borders was necessary for sustaining long-term economic growth as also for augmenting India’s clout in the larger world. He was keen to lead the NDA to victory in the October 2004 general elections on his diplomatic and economic achievements.

Musharraf tried to find out whether Vajpayee would want to speak over the phone. On the evening of 28 April, ten days after Vajpayee rolled his dice in Srinagar, he received a call from Zafarullah Jamali, his newly elected counterpart in Islamabad. Reading from notes prepared in advance, Jamali offered, among others, resumption of train, bus, and air services, full restoration of diplomatic missions. Vajpayee agreed to all except sporting ties, which could backfire unless infiltration came to a halt. What would be the reaction, he asked, if in the middle of a hockey match the terrorists massacre fifty innocents in Jammu?13 The ten-minute call broke the ice. The PMO’s strategy was to move on parallel tracks: talk to the separatists in the valley and the government in Pakistan, then find a way to converge them.

There was another complication. On a trip to Washington in May, Brajesh Mishra received a request that India join the “stabilisation force” in post-war Iraq. Mishra had for a while pitched for an “axis” between the USA, India, and Israel to fight Islamic terrorism. In fact, the US wanted both India and Pakistan to contribute peacekeeping boots on the ground. India was asked to dispatch a division to oversee the administration of Iraq’s Kurdish north.

The government was egged on by a section of the press to accept the US’s request, as it would dramatically upgrade bilateral relations. Preparations began. For the first time, the American embassy briefed New Delhi from classified sources. The US was “extremely keen” because the Indian troops had “plenty of experience” in peacekeeping, “they are well regarded, and they have large numbers”. The Indian Army “identified the units that would be deployed”. Apart from Jaswant Singh and Brajesh Mishra, this time Advani as well as the army seemed open to the idea. The anti-American George Fernandes did not extend “a full-blooded support, but the armed forces had primed him,” and the socialist defence minister allowed himself to be persuaded.

All of this deepened the prime minister’s dilemma. His instinctive reaction had been to refuse: the Indian troops would have to work under an American command. Nor did Vajpayee have the political space for such a commitment. With a raucous opposition, such a move was certain to be vetoed in Parliament. At an all-party meeting as well as over phone calls, Vajpayee prodded the elderly communists to protest more loudly in the street. When the CCS sat down in early May 2003 to take the final call, however, every single attendee backed the American demand:

Advani stayed silent until Vajpayee asked for his opinion: “Aap kya soch rahe hain?” Everyone spoke in favour. Vajpayee just sat, mum. He didn’t say a word. There was deathly silence. He let the silence grow. Then he said, “What would I say to the mothers when their children die?” There was stunned silence again. “No,” he said, “we can’t send our boys.”

Until July, New Delhi’s reaction was to plead with the Americans to first obtain an “explicit UN mandate”. This did not happen. Vajpayee managed to wriggle out citing tied-up hands. Only towards the end of the year – once it emerged that Iraq possessed no WMDs – he went public saying ‘we do not want our jawaans to face bullets in a country which is our friend’.

Iraq notwithstanding, he was received well on his foreign tours during the summer. His most important sojourn in Europe, in the last week of May 2003, took him to Germany, Russia, and France, the three countries which were at the forefront of American action in Iraq. India’s new prestige had to do with a growing economy as well as its relationship with the US. At the same time, India wanted to flex its muscle on its own terms, not as an American satellite. With the leitmotif of Kashmir, he recalled in Berlin how he had once got a picture clicked near the Wall, and now it was happily demolished.

His most important appearance was at a dinner that Vladimir Putin hosted to celebrate the tricentennial of his hometown, St Petersburg. A karate black belt and more than a generation younger than Vajpayee, Putin had confessed “a great fondness” for the Indian patriarch. Except, of course, “if he asked a question on Wednesday, he had to wait till Friday for the answer”. The accompanying media delegation went wild with excitement after seeing Vajpayee seated at the high table alongside the Russian first lady and the Bushes. The host had only aimed at a social mix, but the coverage back home heralded India’s arrival on the world forum.

The prime minister returned to quell a minor rebellion. While he was away, the party president Venkaiah Naidu had suggested that the BJP be jointly led by Advani and Vajpayee in 2004. It was a petty attempt by hardliners, all over again, to test the prime minister’s reaction. Vajpayee was mighty annoyed that Naidu had invited party workers to felicitate him at 7 RCR for his successful foreign trip.

The expelled Kalyan Singh had recently taken a swipe at Vajpayee and Mishra, calling them “tired and retired”. At this felicitation event, Vajpayee threw everyone into a tizzy by declaring that he was neither tired nor retired, but the party must now be led by his successor: “Advaniji ke netritva mein vijay ki ore aage badhein.” Naidu reached the podium to roll back his earlier twin-leader theory, but the damage had already been done. At a closed-door meeting later, Vajpayee chided Naidu for questioning his leadership right when he was breaking bread with the high and mighty world leaders.

Two weeks later, Vajpayee alighted in Beijing for what was his most important trip of the year. The bustling Chinese capital was eerily quiet, with the SARS epidemic at its peak. This was his first visit to the country after the ill-fated 1979 trip. He had recently chatted up the ambassador in Beijing about the metamorphosis of its economy: “Yeh Cheen nein itna chalaang kaise maara?” Over the five days he spent in China, he witnessed first-hand the epic transformation of the northern neighbour, especially in Shanghai: “Such progress is to be seen to be believed.”

At the top of the agenda was the signing of an agreement to reopen the Nathu La pass for trade. The two sides differed over India’s desire for an explicit geographical reference. India was happy to recognise Renqinggang as belonging to the “Tibet Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China”, but the hosts were squeamish about accepting Nathu La as belonging to Sikkim in India. Brajesh Mishra and others burnt the proverbial midnight oil, but failed to convince the hosts.

In a problem-solving mode, Vajpayee signed the joint statement, causing a furore back home. The border problem was discussed “as perhaps never before”, he responded when asked by the press, but rejecting the implication that he had sold out India’s interests. The two countries would continue to remain suspicious about each other’s intentions, and the rest of the border would remain disputed. But China soon modified its maps to show Sikkim as part of India.

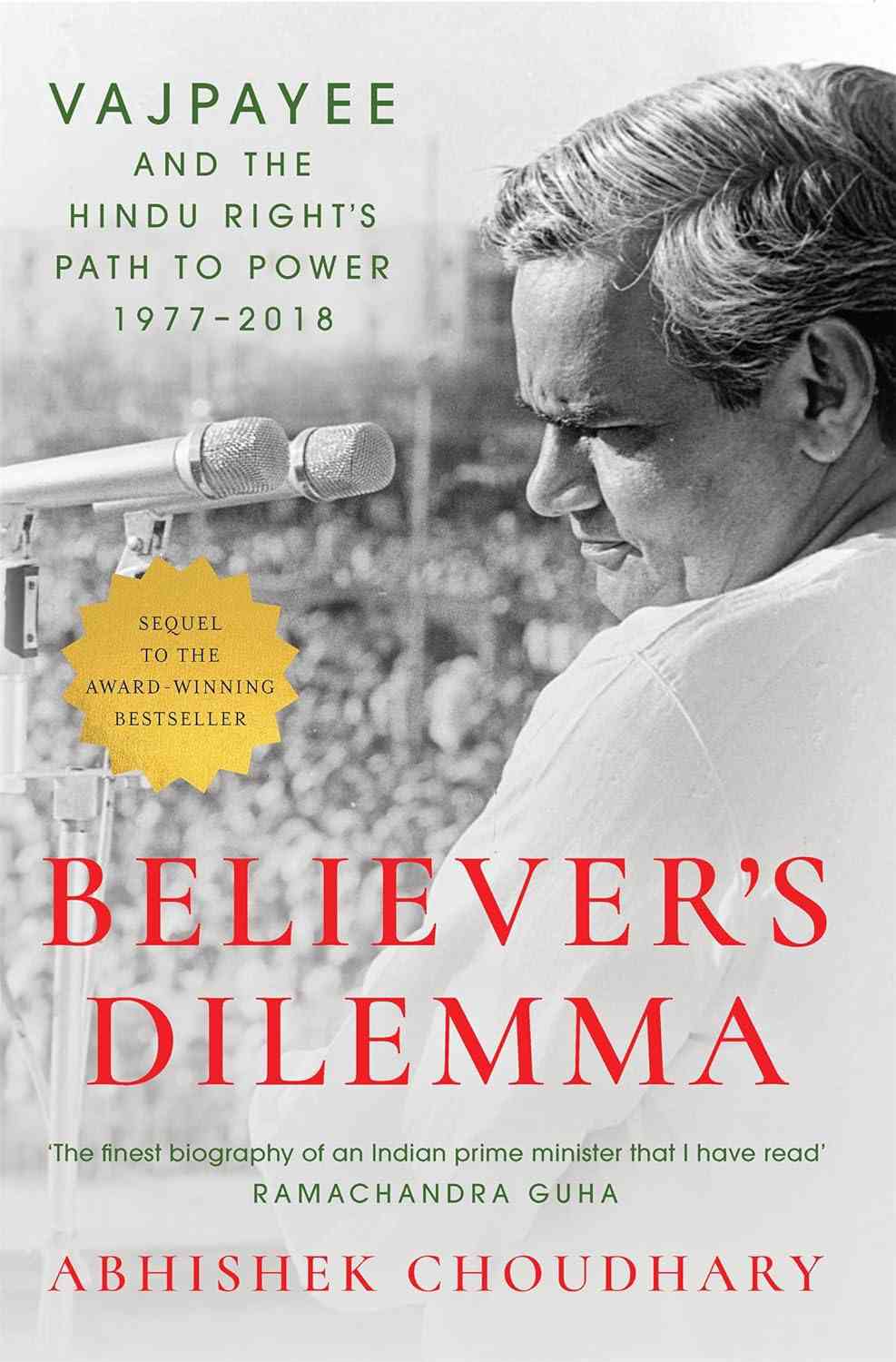

Excerpted with permission from Believer’s Dilemma: Vajpayee and the Hindu Right’s Path to Power, 1977–2018, Abhishek Choudhary, Pan MacMillan India.