These were only the latest of a slew sexual assaults in India that the media has reported over the past year. The past year has seen headlines reading, 'Understanding India's rape crisis' or 'Rape capital image affecting Indian tourism?' Others use anecdotal evidence to place India among the top five least safe countries for women in the world. However, these media reports, both Indian and foreign, strike far from the truth.

“The foreign media always describes India as having the maximum number of rapes, but this is not true,” said Flavia Agnes, a women’s rights lawyer with Majlis Legal Centre in Mumbai.

A comparative report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reveals that India actually has among the lowest rates of rape in the world. As the chart below shows, in 2010, countries like the US, Sweden and Botswana all have higher rates of rape. These figures are based on each country's official records of rape.

To be sure, these figures don’t tell the whole story. India’s reported rate of rape – 1.9 incidents per 100,000 people – is grossly underestimated, experts say. In the US, by comparison, the rate of rape in 2011 was estimated at 52.7 per 100,000 women. These experts point out that the Indian Penal Code expanded its definition of rape only in April 2013, and still does not recognise instances of rape within marriage. In addition, India's National Crime Records Bureau, on which the UN figures are based, counts rapes that end in murder as homicides alone.

There are several reasons for this under-reporting, said Gita Chadha, a sociologist at Mumbai University. “Women do not report rape in order to avoid stigmatisation,” she said. “Often, offenders and rapists are from within the family, reporting become more difficult. The middle classes hesitate to report rape because it is stigmatised. However, for women of lower classes, being raped is normalised violence that it is not even recognised as a crime. If you ask women what rape is, very often they do not know how to define it legally as an offence.”

Besides, the police sometimes refuse to register complaints in an attempt to keep crime rates in their jurisdictions down. In April, for example, the Delhi police reportedly filed a case of rape six years after the incident occurred. The woman in question had to appeal to several authorities before the National Commission for Women finally stepped in and ordered the police to file a case.

Given these factors, it is difficult to estimate the extent to which the actual number of rapes in India differs from reported ones. Countries like the US supplement their official statistics by conducting informal ‘victimisation surveys’ to estimate the number of unreported crimes and to calculate more accurate crime rates. This practice has yet to be adopted in India. Even so, India’s present rate of 1.9 would have to be multiplied several times over to even approach the rates in many other countries.

Based on experience, about one in three rape victims go to the police, said Sudha Sundararaman, General Secretary of All India Democratic Women's Association, the women’s wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

This is not to imply that the lower figures make any incident of rape less brutal. But the gap between the perception of violence and the actual occurrence of the threat has the potential to alter how women act. Activists say that while the increased media discussion of rape has galvanised women to speak against patriarchal violence as never before, this has come at a cost.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that families are imposing more stringent restrictions on women. “We had a couple of meetings with young women in Delhi,” Sundararaman said. “We were concerned to find from their responses that they themselves felt it was better to go home early, tell someone where they are, and so on.”

Gita Chadha of Mumbai University noted that the women’s cells of several right wing political parties have been making videos urging stricter controls on women. “If you look at the analysis in the last ten years, there has been a backlash against women coming out of their domestic circles,” she said. “These instances of rape are being used to push the women back into the domestic sphere.”

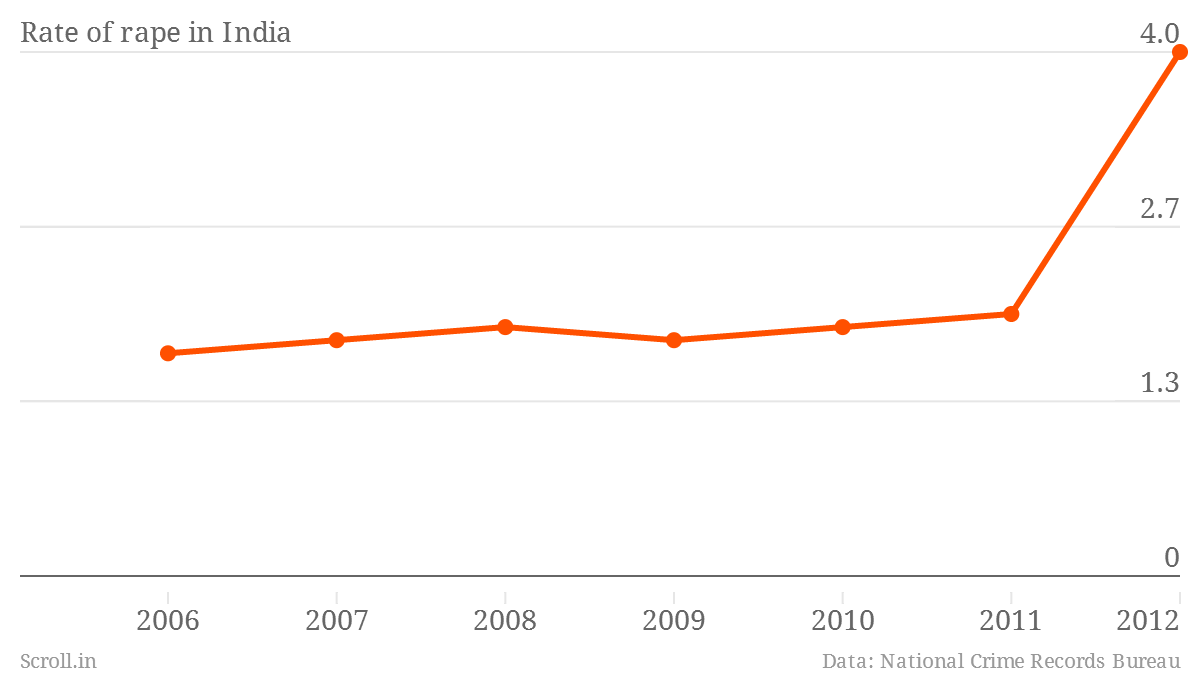

Despite this, there have been positive results. “The visibility of these cases is also giving courage to women, especially young women, to come out and report rape,” said Chadha. Added Sundararaman, “We find that women, rape survivors especially, are approaching the police and getting some measure of social support. This is changing the statistics.”

Even as the number of reported rapes rises to more accurately reflect reality, Indian women would be greatly reassured if another parameter – now stubbornly low – were to be altered, activists say. As these charts demonstrate, the rate of conviction for rapists has failed to keep pace with the increase in the number of cases.

Concluded Sundararaman, “In the whole dialogue around rape, there is at least a slight shift. There is a sense of preparedness, but inwardly also a building up of strength.”