"It was lonely out there," the young man said, showing me on his phone pictures of the small railway station in the hills of upper Assam where he had been posted and from where he had just run away.

We had met aboard a train passing through Bihar. He was in his twenties, and he had landed a job with the Indian Railways after what seemed like an year-long marathon: a written test, followed by a physical test, a medical examination, a merit list and finally, the final list.

But he gave it up within a week of landing at his first posting. “I have submitted a leave application asking for a week’s leave, but I am not going back for another three months. I am going to sit at home and prepare for exams for another job.”

Does he not fear losing this job?

“It is the public sector, they can't scrap my job. Meri naukari nahi khaa sakta."

Bihar's young people move out after school to study and work outside. Those who cannot afford to do so spend long years preparing for entrance exams for government jobs.

"You know the story of Bihar. No jobs, no industry," he said. "What else can we do…"

He asked me where I was headed.

"Begusarai."

"Oh, then you must go and see Leningrad."

***

"I have heard this place is called Leningrad," I went up to an old man, speaking with him in Hindi. We were standing under a market gate with a hammer and sickle perched on top. The village's name was Bihat, and the gate was called Moscow Gate.

"Do you know about Leningrad?" he replied in English. "That tree. That's Leningrad," he said, pointing in a direction further down the village market, to a small enclave with a memorial of Comrade Chandrashekhar, not the revolutionary leader Azad, but Chandrashekhar Singh, the first communist to be elected to Bihar's state assembly.

He had won the 1962 elections. Since then, this part of Begusarai district of Bihar, earlier the Barauni assembly constituency, rechristened Teghra after delimitation, had been represented by the Communist Party of India in an unbroken line until the assembly election of 2010, when newspapers reported the fall of Leningrad: "The Left bastion of Teghra…was swamped by the Nitish Kumar wave today with the BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party] planting its lotus flag on this small township that had been equated with the Russian city that was the hub of the October Revolution."

***

Four years later, the Nitish wave has blown away. The summer has begun. Gusts of dust blow in from the banks of Ganga. The power cuts force men to strip down to banians and sit on charpoys outside. The women have no such options. And the Janata Dal (United) and BJP have parted ways.

The Communist Party of India is JD(U)'s new partner.

In 2009, the JD(U)'s candidate won 205,680 votes in Begusarai, while CPI was second at 164,843.

This time, CPI has put up a candidate, Rajendra Singh, and the JD(U) is supporting him.

In other places in the world, it would be possible to assume the combined vote share of the two parties would lead the candidate to an easy victory.

But not in the multi-party system of India, and the caste arithmetic of Bihar.

For one, in 2009, the JD(U) had the votes of the supporters of the BJP, which it no longer has.

Two, in 2009, the JD(U) had fielded Monazir Hassan, who drew in considerable Muslim votes. This time, those votes are likely to migrate to the RJD candidate Tanvir Hasan.

Three, the CPI is itself faced with internal rebellion, as I discovered in Leningrad.

At an old-style red brick building, stared down by revolutionary heroes, local and national – including both Chandrashekhars, Azad and Singh – I asked an old man how election preparations were going.

"There is gadbadi," he said. "The choice of candidate has led to revolt within the workers. The person who deserved to be given the ticket was sidelined.” Shatrughan Prasad Sigh, a 73-year-old CPI veteran, had lost out to Rajendra Prasad, also nearing 70. Sixteen of the party's 18 block secretaries in Begusarai district had resigned in protest.

The old man, himself in his late sixties, was Ram Ratan Singh, a prominent local leader, who in the communist tradition of Bihar, belongs to the upper caste community of Bhumihars.

Bhumihars see themselves as Brahmins who own and cultivate land.

Elsewhere in Bihar, their control over land has pitted them against the landless Dalits mobilised by the Naxalite movement. In the 1980s and '90s, some of the worst massacres of Dalits were carried out by a Bhumihar militia called Ranvir Sena.

It is the Bhumihar lobby that has blocked reforms that could lead to land redistribution in Bihar. And it is Bhumihar-led CPI that is the strongest votary of land reform in the state assembly.

How do you explain this contradiction, I asked Ram Ratan Singh.

"Individual Bhumihar farmers hold small parcels of land, not large estates. But I agree that pooled together, most of the land in the state is controlled by our people. Now, other parties have managed to plant a fear in their hearts that their land would be taken away if land reforms are carried out. But if I own just five bighas of land, that's less than the land ceiling, how can it be taken away? Other parties are misleading our people and using them to get to power."

By other parties, Ram Ratan Singh meant the BJP, the party seen to have the greatest section of the Bhumihar votes in the state. In the villages of Begusarai, I heard pro-BJP voices over and over again, and they were nearly always Bhumihars. The BJP candidate from Begusarai, 70-year-old Bhola Singh, is Bhumihar, as is his rival in the party, Giriraj Singh, who tried to get a ticket from here but failed. The party eventually accommodated him in the Nawada constituency, keen to prevent a dent in its Bhumihar vote.

So why is a section of Bhumihars in Begusarai still with the CPI?

From conversations, it seemed that the support had more to do with caste pride – the identification with the leaders who are their caste brothers – and less with the party’s ideology.

In fact, the party owes its existence in Bihar to an affront to Bhumihar pride in Bihar.

“Our village’s leader Babu Ramcharitra Singh, who was a freedom fighter, the first science graduate in the district, the minister of irrigation in Bihar government, Congress ne unka ticket kaat diya, Congress denied him a ticket in 1957. People of this area could not tolerate it. They got him to contest as an independent, and even though at that time Congress ki aandhi chal rahi thi, he won.”

Ramcharitra Singh’s son Chandrashekhar contested the next election on a ticket of the CPI. “That day the Congress departed from here and never returned.”

***

“The land that gave birth to the Communist Party of India in Bihar is the land where the party would be buried.” This was JN Bhagat, the man I had met under Moscow Gate. He had retired as the deputy chief of Hindustan Fertiliser Corporation's Barauni unit, a public sector unit that closed down in 2002. Barauni was once the industrial hub of Bihar, with a refinery, fertiliser factory and ancillary industries. The refinery is still around, but not much else. “No new factories have come up since the time of Pandit Nehru,” Bhagat said.

“Why are the Communists doing so badly?” I asked him.

"Because of their bad policies. The factories closed because of their union baazi. Their leaders drew salaries while sitting at home, lazying around and doing politics.”

“People would tell you that we were responsible for the closure of the factory,” Ram Ratan Singh said, when I asked him about it. “But it was the liberalisation policy of the government that was responsible. The government denied workers the benefits due to them. Is it wrong to fight for our rights?”

He might not like the communists, but Bhagat is bitter about the way the government treated the employees of closed public sector units, denying them retirement benefits. “If you’ve been an MLA for two years, you get a handsome pension. If you’ve been an employee for 33 years, you get nothing.”

He keeps his bitterness to himself, he says. His children, like most of their contemporaries, have moved to Delhi, to work in the private IT companies and banks.

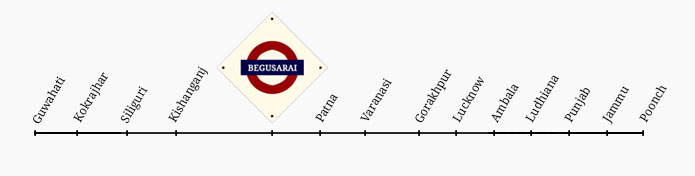

Click here to read all the stories Supriya Sharma has filed about her 2,500-km rail journey from Guwahati to Jammu to listen to India's conversations about the forthcoming elections -- and life.