In a state infamous for the lowest sex ratio in India, the Haryana district of Ambala occupies a position of political preeminence.

Sushma Swaraj, the leader of opposition in the outgoing Parliament, was born and raised here. As was Kumari Selja, the local MP and minister for social justice and empowerment, the only representative in the UPA government from Haryana.

Swaraj might not have contested from Ambala but she's still powerful enough to dwarf Narendra Modi on the BJP posters here – no mean feat, given that even Rajnath Singh, the party president, has failed to do that in Lucknow.

Selja has bowed out of the elections this time, opting for a Rajya Sabha seat, but people in Ambala still remember with awe the way Sonia Gandhi had clutched her arm for support the day she fell ill in Parliament – an image they saw on TV.

Ambala distinguishes itself not only through the powerful women it has sent to Parliament. It has among the highest literacy rates in Haryana, second only to Gurgaon, an extension of Delhi, and Panchkula, an extension of Chandigarh. Its female literacy rate is ten percentage points higher than the state average.

By all accounts, if there is any place in Haryana where women's participation in the political process could be high, it would be here.

One measure of the rising political participation of women in India is the increasing turnout in elections. As The Hindu reported, a study for 16 states in India found that "the sex ratio of voters – the number of women voters for every 1,000 men voters – improved from 715 in the 1960s to 883 in the 2000s. Significantly, this improvement did not come about because more women registered to vote than men, but because more women actively voted."

If women are voting more actively, what are the issues they are voting for?

On Thursday, I visited polling booths in the villages of Ambala, where shalwar kameez clad women were out in full force: in many places, the queues of dupatta-covered heads were longer than those of trouser-clad legs.

Dressed in all pink, from head to toe, Meenakshi Sharma emerged from the polling booth at Mohra village.

"Who did you vote for?" I asked her.

She laughed.

"Ok tell me, what was the basis on which you voted?" I asked her.

"I voted for someone who could be a good leader."

"Who do you rate a good leader among the local candidates?”

"I don't know their names." Then, lowering her voice into a whisper, the woman in her mid-twenties, said, "Actually, my husband briefed me before I came here. He told me that I should press the button next to the lotus."

By then, her sister-in-law, Urmila, emerged from the booth and joined the discussion. She was older and more assertive in the way she spoke.

"Did the Congress do any work here?"

"Mehengai badhai aur kya…It increased the prices, what else."

"So you feel you need to change the government?"

"No, not really," she said. "Mera iraada to tha inhee ko jeetane ka. I wanted to vote for a Congress victory...They have given me a job, after all."

"Where?"

"In the CRPF."

She was talking about her husband's job. A jawan in the Central Reserve Police Force, stationed in Delhi, he is currently travelling on election duty. He could not come home to cast his vote but he made sure he instructed his wife on phone.

"He asked me to vote for lotus. He said it is important to change the government."

"Do all women here follow their husband's instructions when they vote?"

Both Meenakshi and Urmila laughed. "Sunani padhe hai ji. You have to listen."

But the ballot was secret. They could defy their husbands who would not even know, I said.

They laughed and left it at that.

Why defy husbands, a middle-aged woman at another booth replied. "They go out. They know better."

Some woman couched it as 'taking advice'. Others said they did it out of 'respect'. "Koi zor zabardasti nahi. No force or compulsion."

***

Listening to the menfolk, the women have internalized the same worldview, which like in most parts of rural India, is shaped around caste, class and the agrarian economy.

Ambala is set apart from the rest of Haryana by its demographic mix.

Dalits are numerous enough to have made Ambala the only reserved constituency in the state.

The population of Jats, the dominant land-owning caste, is negligible.

Instead, land is in the hands of Punjabi-speaking Sainis and Brahmins, who are locked in conflict with the mostly landless dalits, who work their fields.

Driving through Naraingarh block past ripening wheat fields, which would soon make way for paddy on land fertile enough to yield three crops in an year, I arrived in Gadrauli village, where a group of Saini women sat on charpoys, having cast their votes. Their shalwar kameezes were bright and colorful with sequins and embroidery. They wore make up. They chatted in conviviality.

“Who’s standing for elections here?” I asked them.

They looked at each other in confusion before one of them said, “Ratan Lal Kattaria.”

Kattaria is the BJP candidate from Ambala.

“Who else?”

“Kejriwal?”

They laughed at their own ignorance.

“Looks like you have all voted for BJP,” I said. “You know only the name of the BJP candidate, after all.”

They laughed again.

A woman named Shashi Bala explained, “The Congress has done nothing for us, gareeb loggaa waaste kuch nahi kiya.”

"Why do you call yourself poor. Your fields look great. The area looks very prosperous."

“You don’t understand agriculture, it seems. Do you know how expensive it is to get labour to harvest the crop? The government is giving them food grains for free every month. They don’t need to work anymore. They keep demanding higher wages every year. We, zamindars, have no option but to buckle in.”

“Humara waste kuch bhi nahi hai chamaara waste sab kuch hai, The government has given us nothing. Everything has been given to the chamaars,” an old woman intervened.

“Their children are getting jobs without any hard work while our children stay up all night to study, getting only four hours of sleep, and then they have to go out in search for work,” said Shashi, whose son got an engineering degree from a local college and moved to Bangalore for work. "He has just started out. He does not earn a lot. We are sending him 20,000 rupees every month... Kharcha to ho hi jaata hai. Things nowadays keep getting more and more expensive."

"How much is the daily wage you give to your workers?"

"Poocho mat. Rs 200-Rs 250 rupees a day in harvest season."

At the polling booth inside the village school, it was easy to identify the dalit women. They wore pale and worn out shalwar kameezes. Their faces were sunburnt and their hands calloused.

“Who are you voting for?”

“Jisko aap kahenge uske daal denge. For whomever you say.”

“Who are the candidates in the fray?”

“We don’t know…We vote for the symbol.”

A few more questions, and it emerged that the women were voting for the Congress.

“Has the Congress done any work here?”

“No one does any work.”

“So why are you voting?”

“Je na daale vote to kandum karni hai. Not voting means wasting your vote.”

“Has Selja visited your village?”

“No,” said one woman. Another interjected, “She had come some years ago.”

An older woman began reminiscing about Indira Gandhi.

“Tell me, are you children getting to study? Are they getting jobs?”

“They are studying upto 15th class [graduating from college] but they aren’t getting any jobs. Phir rahe hai, dihaadi kar rahe hai. They are roaming around looking for daily wage work.”

***

The only thing that unites all women here – Dalit, Saini, Brahmin, Bania – is a lack of autonomy that extends from voting decisions to personal choices.

Ultrasound clinics are ubiquitous in Ambala.

All of them have put up the mandatory poster declaring that sex determination tests are illegal.

But a doctor at one of the leading clinics said the only thing that kept doctors from doing sex determination tests was their conscience. Legal enforcement of the ban on sex-testing, Dr Rajeev said, was a farce. “They come and check our records and they harass us if there are minor errors – like say, I have failed to sign the Form F twice.”

Form F is the form that ultrasound clinics need to maintain for cases of pregnant women.

“Filling the form correctly does not rule out sex determination, as making small mistakes does not prove you have done it,” he said. “Instead I would say the government should legalise sex determination, find out the sex of the foetuses and then keep track of the female ones till the child is born. Parents should be held responsible. If you have aborted a female fetus, you should be made to answer why.”

***

If there is one place where women seem to enjoy some freedom, it is Ambala's wholesale cloth market. Famous in the region for its bridal lehengas, women from as far as Punjab flock here in groups to haggle with shopkeepers.

A group of young women shoppers took offence to my questions on gender inequality. "We are equal," a woman dressed in western clothes said. They were here to shop for a wedding. The would-be bride asserted, "I have done my BSc.” Her friend added, "And she'll do her MSc after marriage."

I explained that I didn't mean to suggest that all women in Ambala were being denied freedoms, but surely if so many women in the villages were basing their voting choices on what their husbands diktats, there was a gender issue at hand. "If that is happening, it is wrong," they said.

It took an older woman to offer more perspective. "Yes, freedoms are limited here," said Kamlesh, a short statured woman in her late thirties, who had come to the market with her 16-year-old daughter and three year old son. “Now, before coming here, I had to ask ki market jaaye ki na jaaye,” she said, with a laugh.

"People here are very careful about 'izzat' (honour),” she continued, “and that's why they do not allow women to go out. If women go out less, they feel less confident." It is this lack of confidence that makes her turn to her husband for advice at the time of elections. But doesn’t she watch TV to get to know to news directly, I asked. "We can't believe the news we see on TV, can we?"

Is it true that sex determination tests are still common?

“Yes,” she said. “Jitna marzi sarkar kar le, people still get it done.”

Why, I asked.

"If you have had two daughters, the third time you are pregnant you would like to check once…else your mother-in-law would make life difficult for you. I too had two daughters…”

“So did you go for a test the third time?”

“No, I did not,” she said, “I had full faith in Mataji that she would fulfill my wishes (for a son).”

"Why do people want sons? To take care of them in old age?"

"Sons are good for nothing. Ladkiyan to phir bhi pooch leti hai. Girls still take care of the parents well-being.”

"Then why do people want sons so badly?"

She did not have an answer.

***

In the evening, as voting drew to an end, I met an old woman in her seventies who sat outside the polling booth.

“Who did you vote for, Mataji?”

“I don’t know. I pressed the button that he asked me to,” she said, referring to her son, who had accompanied her inside the booth, since she couldn’t walk on her own.

“Which button?” I asked.

“I couldn’t see. My eyes are failing me.”

“Have you always voted?”

“Hamesha,” she said, with a firm nod of her head.

“Who did you vote for when you were young?”

“Whoever I was asked to vote for by the father of my children.”

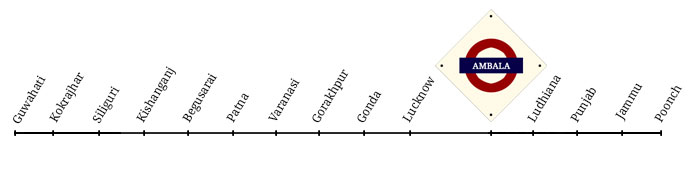

Click here to read all the stories Supriya Sharma has filed about her 2,500-km rail journey from Guwahati to Jammu to listen to India's conversations about the elections – and life.