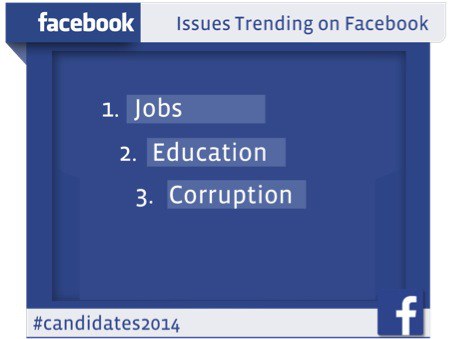

It is no coincidence that the national parties that were late adopters or did not have a social media strategy also acquired the image of non-transparency, out of sync with the aspirations of the youth, first-time voters and other key voting demographics in the country. Undoubtedly, this was India’s first election with such large-scale usage of technology, open-access internet platforms to connect, build conversations, share, mobilise opinion and citizen action. Prime minister-elect Narendra Modi saw this first-hand and had the first-mover advantage in using these technology tools to reach out to India’s huge youth demographic. These elections were about jobs, fighting chronic corruption and restoring leadership, amid a lost half-decade of drift and diminishing governance. The consistent top themes we saw on Facebook:

What does a “like” mean? Can it really translate into votes? From the start, Modi ran the campaign like a US presidential election and took a commanding, front-row seat in building a community and driving engagement. When the December 2013 assembly elections were concluded, Narendra Modi already had eight million fans on Facebook. On March 6, when elections were announced Modi had already crossed 11 million fans. As the national campaign momentum picked up, Modi’s fan base increased by 28.7% crossing 14 million fans by May 12 — the second most “liked” politician on Facebook after Obama.

Modi’s Facebook content curation strategy was well integrated with ground events. The photo showing him calling on celebrated film star Rajinikanth was liked, shared and commented upon by more than 2.2 million people.

In addition, the campaign mounted other support networks and communities on Facebook like “India 272+” volunteering program, used the BJP’s party’s official page to organise a massive mobilisation.

We launched our Election Tracker on March 4 and consistently, BJP was the no. 1 party and Narendra Modi the no. 1 leader throughout the campaign and nine phase voting period.

From the day elections were announced to the day polling ended, 29 million people in India conducted 227 million interactions (posts, comments, shares, and likes) regarding the elections on Facebook. In addition, 13 million people engaged in 75 million interactions regarding Modi. On each day of polling, Facebook ran an alert to people in India letting them know it was Election Day and encouraging them to share that they voted. This message was seen by over 31 million Indian voters. And as poll results were called, Modi’s photo with his victory wall message generated more than a million likes and shares.

Openness, sense of community, and freedom are inherent characteristics of the internet. These attributes both help build momentum, mobilise and also challenge. Political parties will need to recognise this and embrace this equalising tool. Those that do will succeed.

In politics you will have to connect and share. Ultimately these are core values of a vibrant democracy. The 2014 election results firmly established that.

Ankhi Das is the public policy director for India and South Asia at Facebook.