While jellyfish are commonly seen across the Indian coast, upside-down jellyfish are rarer. In lakes, they are even rarer. Only a few lakes in the world, located in Indonesia and the Philippines, have upside-down jellyfish.

“There might be other lakes like this in India, but nobody has yet made them known to the world,” said BC Choudhury, a senior advisor with the Wildlife Trust of India, which made the announcement this week after months of research following the initial sighting.

Upside-down jellyfish typically live at the bottom of the sea near mudflats, shallow lagoons and mangroves. Their bells are fixed to the bed, while their tentacles sway upwards to catch prey. This is the only species of jellyfish that lives entirely upside-down.

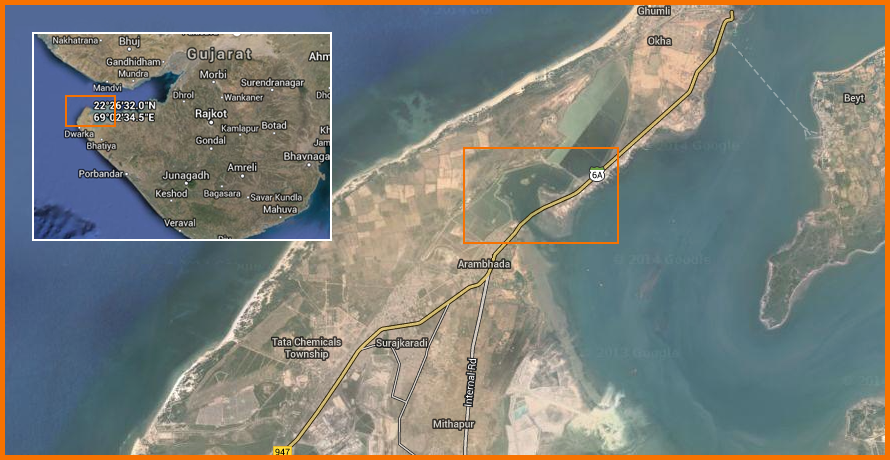

The conservationists found the jellyfish in Arambhada lake, located between Okha and Dwaraka. The lake lies between salt flats and wastelands on one side and the Gulf of Kutch on the other.

About two decades ago, according to locals, a culvert was built across a backwater near Arambhada. The culvert partially blocked a shallow backwater depression already present where the lake is today. With direct access to the sea cut off except for a small canal under the culvert, the backwater became a lake.

A year and a half ago, local fishermen told scientists at the Wildlife Trust of India station in Mithapur nearby about marine turtles that might have been trapped by the bridge. The conservationists had been working in the region for the past decade on a project to replace the dying coral reefs of the Kutch with corals from Lakshadweep. A team of three biologists and one sociologist is stationed there.

“We heard there was a population of marine turtles in the lake,” said Choudhry. "They are supposed to be in the sea, so we wanted to know how they came to the lake. Our plan was to rescue the turtles, attach satellite transmitters to them and do a survey of the lake. But we were thrilled to see the quantity of sea grass and jellyfish in the lake.”

“During our recce on the first day, we saw a lot of jellyfish, but we didn’t think too much about them,” said S Goutham, a marine biologist with the Trust. “Only after we went back to the lab and began to research them did we realise that this might be the first recorded instance of upside-down jellyfish in a lake in India.

Most jellyfish species are free-moving planktons that drift with ocean currents. They might appear at one location only for a few weeks in a given year. Jellyfish blooms appear in irregular quantities all along the coast of India.

"There is a bloom between October and November only for 15 days along the Andhra coast," said Gotham. "So people and companies harvest the (barrel) jellyfish, process them and send them to China. They come there only during blooming time.”

The upside-down jellyfish bloom at Arambada, however, remains in that place all through the year, which Goutham says will make them easier to study. “We know very little about the life cycle of this jellyfish,” he said. “We know that during one season, they release small masses of jelly for reproduction.”

During that season, fishermen’s skins get entirely red. “They think it is because of the change in temperature of the water,” said Goutham, “but it is likely to be jellyfish stings.”

Only four fishermen actually fish in the lake, which is used as a mangrove nursery by the locals and for experiments by the fisheries department.