The National Democratic Alliance’s move to dilute the previous government’s Land Acquisition Act, the first major change in the rules governing land acquisition in more than a hundred years, has also prompted concerns that an already scarce resource is about to be given away without due consideration. Before delving into that debate, however, it should be useful to just get an idea of how India’s land is being used currently.

For centuries, and perhaps even longer, the Indian economy has been dominated by agriculture. The nation’s land use statistics don’t suggest any different. In 1950, agriculture contributed about 50 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product and, correspondingly, around 57% of the country’s land was being used for it. Over time, the contribution to GDP has come down significantly – to just around 14% in 2012-13 – but the amount of agricultural land has remained the same, with seasonal fluctuations in the net sown area depending on the performance of the rains.

As per statistics issued by the Ministry of Agriculture, the amount of land in non-agricultural use, including industry, residential areas and infrastructure, has risen significantly over the past five decades, but remains a minuscule portion of the overall land use of the country. In 1950, it was just 2.85% of all the land used in India, and by 2010 that number had gone up to 8%.

It’s worth comparing these land use statistics to those in other countries, with India clearly using more land for agriculture than the United States, Pakistan and all of the other BRICS countries barring South Africa (the caveat being that only a tiny percentage of South Africa’s agricultural land is actually considered arable and cultivated). Just like India, South Africa faces a similar situation, where only 10% of its GDP is generated from farms, though a massive portion of the country’s land is dedicated to agriculture.

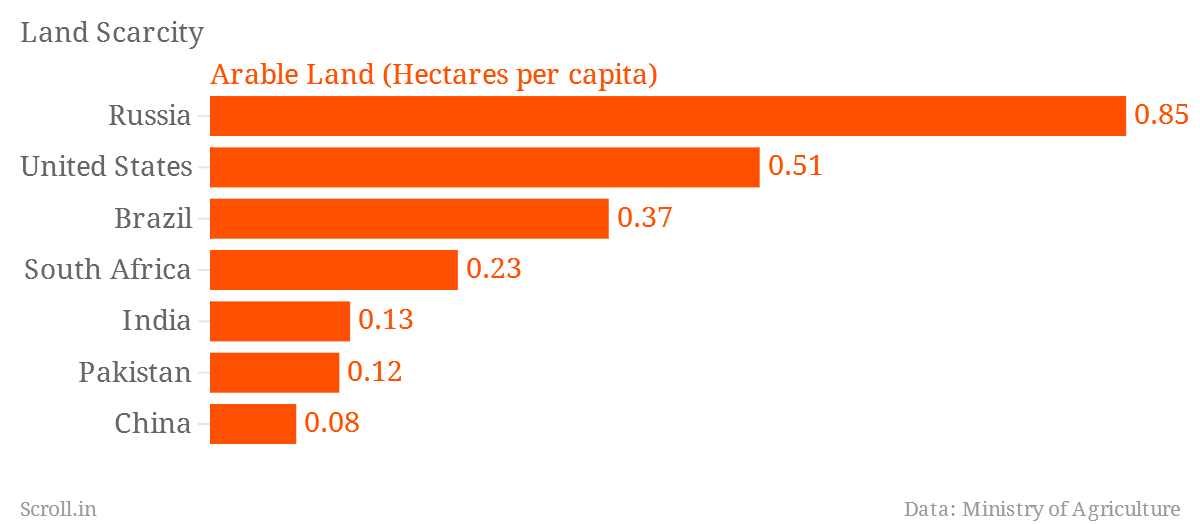

With agricultural land remaining constant and the population exploding, the amount of arable land per capita has gone down significantly. This measures the amount of agricultural land potentially available to each person in the country, which puts India far below other BRICS countries as well as those in the developed world, except for China and Pakistan.

The country remains overwhelmingly agricultural, with a central belt stretching from Punjab to Bihar cordoning off more than 70% of their land for farming. The rest of the country doesn’t particularly lag behind, with only Jammu and Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh using less than 10% of their land on agriculture.

The relative proportion of non-agricultural usage is much more surprising, however. Here, Bihar and West Bengal taking the lead. These aren’t states generally associated with much industrialisation or development, although West Bengal does have a surprisingly high volume of roads. The two southern-most states, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, also dedicate a large amount of their land to non-agricultural use.

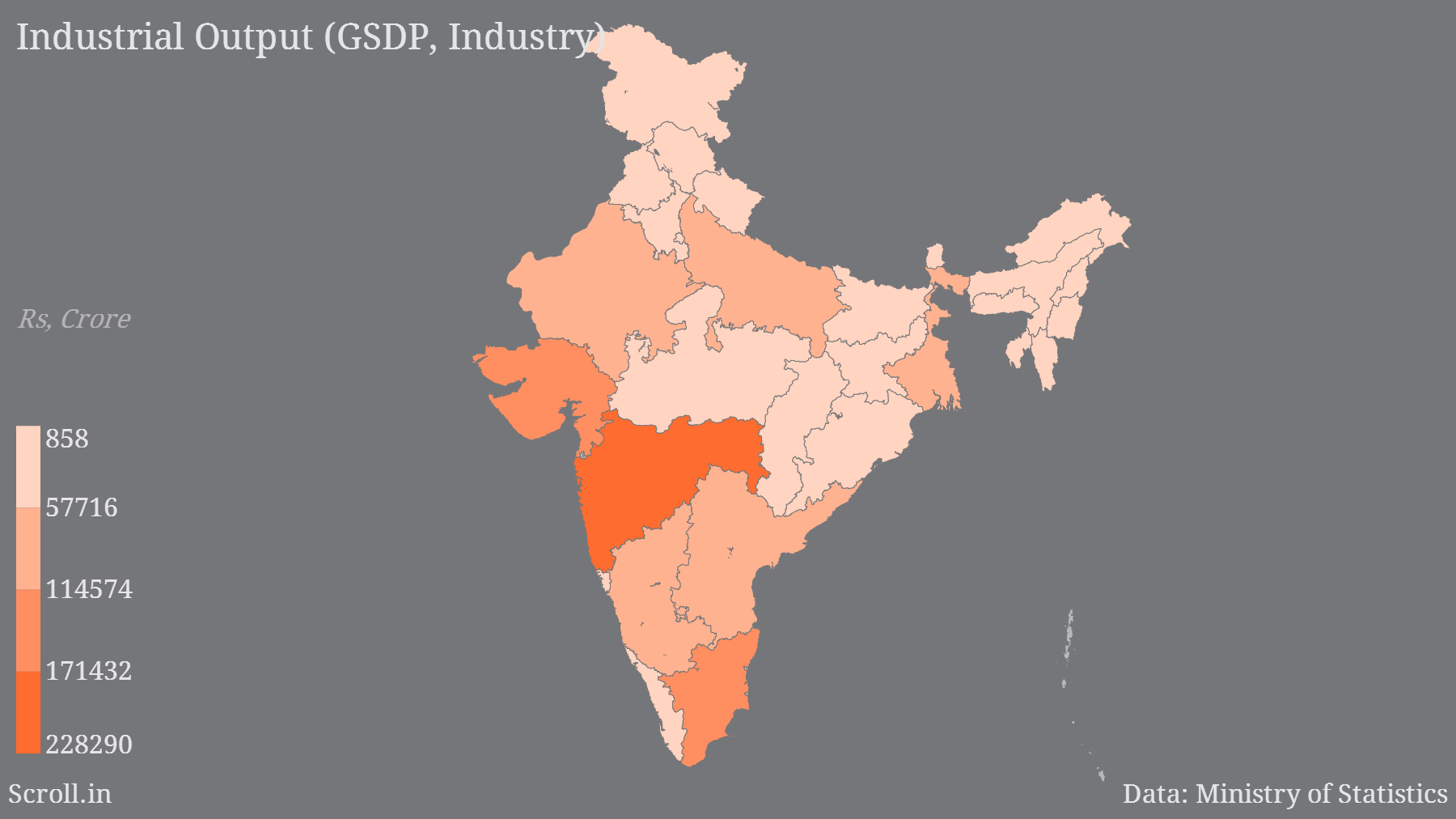

These numbers are somewhat surprising especially when you hold them in comparison to the states’ industrial production. Less than 5% of Maharashtra’s land is given over to non-agricultural usage, yet its industrial output is by far the most in the country. Bihar, on the other hand, despite having 18% of its land in non-agricultural use, lags far behind in industrial output.