People caught in the conflict zone have been communicating to the outside world via social media. But even as reporters in Gaza file stories vetted by editors behind news desks far away, they are posting 140-character, real-time, emotional descriptions and pictures from the war zone.

This has set off a debate in the Western media about whether journalists in the Gaza Strip are truly being neutral.

This round of violence began in early June, when three Israeli teenagers hitchhiking in the West Bank were kidnapped and killed. Their bodies were found on June 30. Israel blamed Hamas for the act, which the Palestinian organisation denied. The violence has escalated into an all-out war, with Hamas firing rockets into Israel and Israel carrying out air strikes on Gaza.

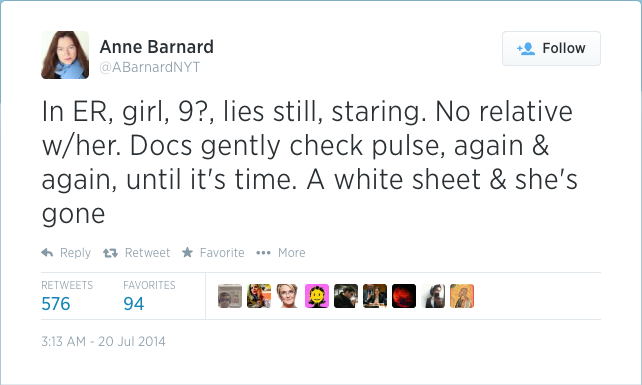

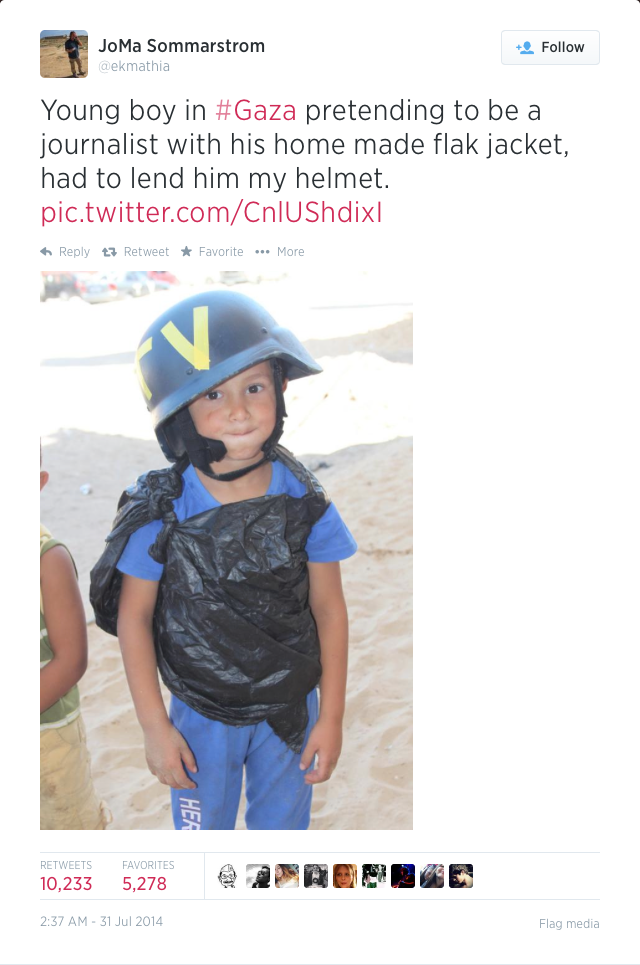

But the death toll is skewed – three Israeli civilians and 56 Israeli soldiers have died, compared with more than 1,700 Gazans, of whom 80% are civilians. As a result, almost every journalist reporting from the ground has felt compelled to tweet about plight of the Strip's children.

It’s cold comfort that the despair of Gazan children is winning Palestine the social media war. In late July, the hashtag #GazaUnderAttack had been used more than four million times while #IsraelUnderFire had been tweeted about 200,000 times.

These are some other tweets that went viral:

Allen Sorenson, journalist with the Danish daily Berlingsk, posted a photo of Israelis gathered to watch to bombing of Gaza that was retweeted 12,000 times.

Reporting from a hill overlooking the Israel-Gaza border on June 17, CNN's Diane Magnay sent this tweet out after doing her live shot: “Israelis on hill above Sderot cheer as bombs land on #gaza; threaten to ‘destroy our car if I say a word wrong’. Scum.” The tweet was later deleted and Magnay reassigned to Moscow soon afterwards.

On July 16, Ayman Moyheldin of NBC tweeted about an Israeli airstrike that killed four boys playing on the beach near his hotel. He followed that with a Facebook post about the US State Department saying that Hamas was “ultimately responsible" for the children’s deaths.

The Facebook post was deleted and Moyheldin was replaced in the war zone by foreign correspondent Richard Engel. He returned after a few days only to announce on August 4 that he was going on a month's leave.

Some worry that by bypassing conventional news filters, like an editor's desk, tweets and Facebook posts open the gate to a minefield of bias. But others argue that there is a value to uncensored reporters' tweets and Facebook posts, in which they describe what they see and feel.

In his column on August 1 in The Guardian, Giles Fraser said that while the traditional news media standard is to maintain strict boundaries between objective and subjective, “being calmly rational about dead children feels like a very particular form of madness. Whatever else journalistic objectivity is, it surely cannot be the elimination of human emotion. If we don’t recognise that, we are not describing the full picture.”

Geeta Seshu, editor of the Free Speech Hub at The Hoot, a media criticism website, said journalists must abide by the expected standards of news-gathering and verification, especially when using social media. “I wouldn’t advocate restraint as much as judgment,” she said. "But if you exercise self-censorship then you might also be causing damage to the issue."

Stopping to think before tweeting can be called self-censorship or merely being balanced. Even in the immediate and urgent nature of this form, it might make sense for journalists to take a moment to compose their sentences, argues Vibodh Parthasarathi of the Centre for Culture, Media and Governance at New Delhi's Jamia Milia University.

“Before tweeting, I would imagine a person would want to ask themselves ‘Will this affect my credibility or not?’" he said. "That should be the major touchstone of a response on social media."