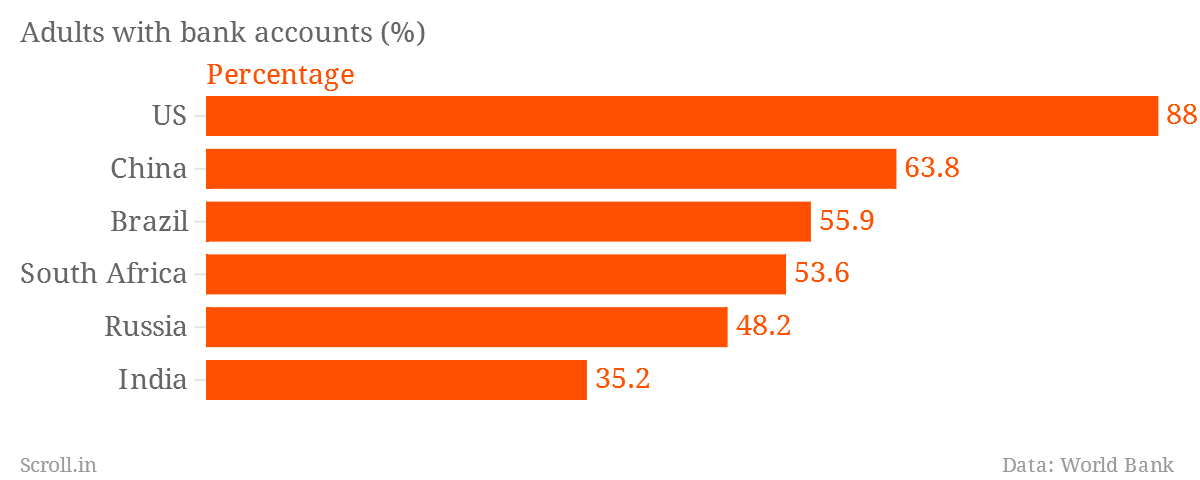

A whopping 65% of India’s adult population has no account in a formal bank and many of those who have signed up rarely have access to the full range of services a bank is supposed to offer.

As a way of addressing this problem, the Modi government has announced incentives that should appeal to both the unbanked, such as built-in life insurance with every bank account, while also giving banks a reason to bring more people into the formal financial net.

For the plan to work though, much depends on the humble business correspondent.

Bank agents

In 2006, noting that the traditional branch-banking system was not doing enough to improve financial inclusion, the Reserve Bank of India decided to turn to a new model. The RBI allowed banks to employ an intermediary called a business correspondent, who could travel to areas where there are no branches and carry out transactions on a bank’s behalf.

The initial guidelines allowed BCs to do everything from helping open accounts to making deposits and withdrawals, and even identifying customers for certain loans. BCs worked primarily with what were earlier known as no-frills accounts; basic savings accounts with no minimum balance and fewer paperwork requirements.

Initially, only non-profits were allowed to be banking correspondents, but over time RBI has made it easier for other organisations to join in. Today, according to the central bank, there are more than 2.2 lakh BCs. Microfinance institutions, PCO phone operators and grocery-store owners all act as agents for banks.

“As of March 2012, banks had covered 74,199 villages, or 99.7% of the target assigned to them," reported a study carried out by the New America Foundation and MicroSave. "Two years earlier, banks had 21,475 branches in rural areas, but by March 2012, they provided banking services in rural areas through 138,502 outlets, comprising 24,085 rural branches, 111,948 BC outlets and 2,469 outlets through other modes such as ATMs and mobile vans.”

Accounting errors

Although those numbers are impressive, few assessments of the BC model’s application so far have been complimentary. Surveys and reports across the board have suggested that while there has been a substantial rise in bank accounts being opened, these very often go dormant quickly or are only used to receive money doled out by the government as subsidies.

More problematically, the BCs aren't quite doing what they are expected to. A survey carried out by the RBI and the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor found that 47% of the banking correspondents they attempted to contact were untraceable. Worse, up to 16% of the ones that they were able to get in touch with had not carried out a single transaction till date. As a result, while access to bank accounts has gone up tremendously on paper, those living in far-to-reach areas continue to have to go to informal sources of credit for their financial needs.

“The message that comes out of the event is loud and clear – the focus of the model has to shift significantly to ensure that it finds space in the business strategies of the banks and not in the footnotes of their annual reports,” concluded a review of the BC model carried out by the RBI and CGAP.

According to the review, BCs reported up to 80% of savings accounts they had opened were dormant. They also found that the commission paid by banks for their efforts was not adequate for the model to be viable, with training and equipment needs. Banks, meanwhile, regularly complain that the BCs failed to properly market their products and are unable to reach out to potential customers in many areas. The MicroSave survey listed 100% of the BCs spoken to complaining that they were operating in a high-cost low-profit environment. Others complained about inadequate support from banks or restricted product offerings.

“The result is high levels of demoralisation, demotivation and attrition amongst agents across the country," said a separate MicroSave policy brief. "The business models being implemented by banks lack analysis of, or focus on, the preferences and expectations of poor consumers, who want differentiated services (in terms of products on offer, service quality, security, protection and so on) and are willing to pay for these.”

Incentivising agents

The Modi government is hoping to salvage the model by offering carrots to both agents and customers to encourage more financial activity. The prime minister in his speech announced that business correspondents would be given a monthly remuneration of at least Rs 5,000, with variable components based on how much business and how many transactions are carried out.

Meanwhile, the Jan Dhan Yojana also seeks to open bank accounts for every household with an overdraft facility of Rs 5,000 – dependent on a short course in financial literacy – as well as an immediate RuPay Debit Card that comes with Rs 1 lakh in accident insurance cover. These tweaks, as well as further efforts from the RBI to reduce restrictions, could improve India’s financial inclusion substantially – but much of it will come down to how banking correspondents respond to the measures.

“There are millions of families who have mobile phones but no bank accounts,” Modi said, during his Independence Day speech, while introducing the new scheme. “We have to change this scenario. Economic resources of the country should be utilised for the well-being of the poor.”